Why Are We So Terrible At Contacting Aliens?

by John Wenz

In Stanislaw Lem’s 1968 novel His Master’s Voice, a message bubbles up from an underground fringe community that comes to be regarded as a message from an alien civilization.

A group of scientists are secretly assembled by the United States government to crack the message. For the most part, they fail. They run through some math, come up with a genome, use it to pop out a useless goop that can sort of kind of teleport things with absolutely no precision, and continue to search for meaning in the message. They fail.

The book served as a sort of treatise on the problem of communication with an extraterrestrial society. Such communication would be next to impossible, Lem thought. He always wrote a cynical view of sci-fi — especially where aliens were involved. His thrice-film-adapted novel, Solaris, involved attempts to communicate with an intelligent lifeform on a distant planet … until the realization is made that the planet itself is the intelligence, the ocean on the planet a super-organism. That ocean is not unlike the LUCA superorganism theory; that’s an acronym for a theoretical Last Universal Common Ancestor among current life back at the unicellular level — which, according to those backing the superorganism theory, was a big sea of goop that swapped genes to survive.

To Lem, the attempts to contact aliens were a lesson in futility because we can’t actually think like those we’re contacting. We have a variety of intelligent species contemporary to human beings with whom we cannot begin to communicate. Also: sometimes members of our own species.

In 1985, Carl Sagan brought forth a much less cynical — if more convenient — view on the first contact scenario. The book was called Contact. It was later made into an above-average movie with Jodie Foster that, when I first saw it, I was convinced deserved every Oscar in 1998.

In the novel, a scientist — a great, real, fleshed-out female character who deals with all varieties of academic mansplaining — leads the radio astronomy team that discovers a transmission coming from a region of sky where there’s no planet yet, in the still-forming star system of Vega.

The transmission involves what at first appears to be just footage of Hitler at the 1936 Olympics, but which later proves to have messages hidden interlaced inside. It includes instructions on building a bizarre machine which opens a wormhole to other wormholes, landing at a spaceport with conveniently telepathic aliens, who reveal a universal thumbprint of a creator.

The species appears to take on a similar role to the benign aliens of Arthur C. Clarke’s excellent Childhood’s End, a caretaker species who introduce human beings to the next step in their evolution and just happen to look exactly like Satan. (Spoiler: They’re not Satan. They’re really nice.)

Rather than making human beings into beings of pure light, an idea that the various iterations of “Star Trek” would reuse a billion times over, Contact’s caretakers show humans a universal arithmetic instilled by somebody, who is totally not God, but might be God, because they made it so that pi in Base 11 reveals an intelligence. Or something?

At any rate, a number of convenient dei ex machina propel Sagan’s novel. The Berlin Olympics transmissions from earth are found by a satellite of the species who don’t live on Vega. The signal didn’t suffer from signal degradation, despite potential for interference and other problems between here and Vega, 25 light years away. In addition, the aliens are telepathic, so once we meet them, we can talk to them. Because they’re in our brains, appearing as “human” to us, never showing their real shape or form.

And the way the initial message is encoded actually makes logical sense. The original message is sent as a series of prime numbers. By sending prime numbers, the message reveals that it comes from an intelligent source, rather than a pulsar or quasar emitting radio signals out of their design. Sagan finds a convenient method for establishing communication — math, a universal language. At least if you’re not of the mind that humans invented math and it doesn’t really exist except as just another language.

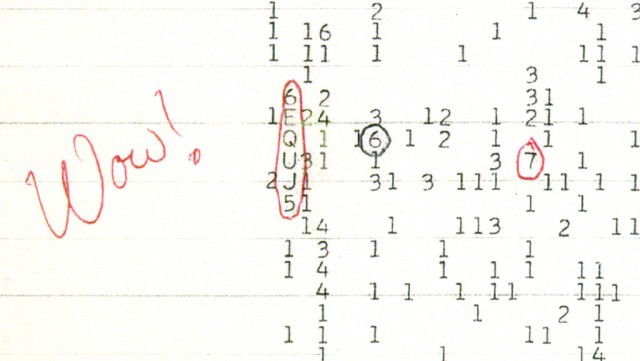

In 1977, a message was received at the Big Ear radio telescope in Ohio. It was in the right spectrum and of the right shape to give all the hallmarks of what we might look for in a communication with extraterrestrials. It lasted 72 seconds, until it was out of range, and its recording discovered the next morning. The message never repeated, thus leaving all of the efforts for the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence with 72 seconds of indecipherable something or other that may or may not be from another planet.

Because, like the message in Contact, it comes from a place it shouldn’t have. It came from a completely blank patch of sky.

At any time, thousands of computers are sorting through SETI data, looking for another “Wow!” signal. (It was called the “Wow!” signal because the discoverer printed it out and wrote “wow!” on it.) This is because SETI is now a private venture, and they’ve turned to a program called SETI@Home to sort through the data. SETI@Home is an early example of cloud computing, except no one would call it that because only total dorks were doing it and not companies with lots of money.

I’ve been participating since 1998.

In 2008, Bebo, the currently shuttered social networking site, invited site members to add their own scrappy message to a larger message being sent to a recently discovered planet orbiting Gliese 581. It consisted of photos, videos and text messages.

You know, in English.

Let’s go back to Stanislaw Lem. The message is never fully deciphered because it can’t be deciphered because we can’t understand extraterrestrial intelligence. With Carl Sagan, we can decipher the message because they sent it to us in a way meant to be decoded, which it’s assumed by Sagan anyone would understand, because it’s math, which many believe to be a universal language.

So straightaway, we violated one of Lem’s quandaries with our message. We didn’t even attempt to approach in good faith. We sent gibberish to the first maybe-habitable maybe-planet we found.

Granted, other, better examples have been served up by scientists and mathematicians, including the golden records on both Voyager crafts, which tell about humanity in pictograms and sounds. Provided, of course, other cultures will work out what a phonographic recording is. (There again, we’re making the assumption of the ability to understand visual or audio cues.)

In nature, animals who live in dark regions over time lose the ability to see. The well-named Texas blind salamander has no eyes at all. Another blind salamander species, the olm, navigates by electrical signal, a method employed across the animal kingdom, including by the primitive, egg-laying mammals known as monotremes. That group includes the platypus, which both spends a lot of time underwater and can’t see underwater at all, necessitating moving by electrical signal. And let’s not get started on our underwater cetacean and delphinidae overlords, the devious whales and dolphins who use sonar.

In 2012, we returned the “Wow!” signal. We did so through Twitter. In English. Stephen Colbert sent a video message telling the maybe-or-maybe not aliens that humans were terrible to eat and “kind of gamey.”

Sent from the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico, the technicians at least had the good sense to include a repeating sequence in the message, making the maybe-aliens aware that the strings of 140 character gibberish were written in the Latin alphabet.

In 1974, a transmission called the Arecibo Message was sent to a satellite galaxy 25,000 light years away. It displayed simple message about the location of Earth, an 8-bit rendering of a human, the form and function of DNA and a few other things. It’s at least a crude attempt to give a message a simply-understood shape or form. It was one of a handful of more “serious” efforts, though I do rather like the sounds of the first interstellar theremin concert: In 2001, kids at a Russian teen center broadcast text and music from the Yevpatoria telescope. It was sent in both Russian and English, which surely would not be confusing to aliens.

We’re beginning to understand-ish, in a very loose sense, what animals are saying. We now know that prairie dogs call us fat, for instance. And that dolphins have names for each other, assumedly so that they can best conspire to murder us all.

There is also distributed intelligence: Slime molds, ant hills, naked mole rats. There’s no language, per se, but an intense social structure and a hive mind. And, in the case of slime, a billion different genders, give or take. (No really, read Dr. Tatiana’s Sex Advice to All Creation.) This sort of distributed intelligence has been put forth by some to be the direction artificial intelligence must take to emerge. In trying to find a way to make artificial intelligence work, we’ve been trying to artificially construct human intelligence, not looking at other forms of intelligence that exist around us.

It’s sort of a macro version of semiotic domains, an idea that says that literacy isn’t reading — that literacy is sort of anything, really. Literacy is actually a system that you understand. For example, a small child may not be able to read yet, but he might understand the schematics of a particular video game and understand its visual cues. Preverbal children might also understand, use and teach each other Baby Sign Language. That constitutes its own literacy.

There are some scientists who say that even by concentrating on radio alone we’re losing potential messages. There are a host of other things that might happen. A big flash of laser light in the sky. Gamma rays. Robotic invasion bringing humanity to its knees. The “X-Files” episode where aliens send fake cockroaches as probes.

According to The Secret Lives of Lobsters: the military once developed a robotic lobster. Some researchers used it to study lobster habitats, but also seedier areas of the military-industrial complex were looking at maybe weaponizing them. Weaponizing robotic lobsters. If it can happen here, certainly it can happen on other planets.

So: we have a variety of means by which we might get a message. We have a couple ideas on how we might understand it. We’ve sent a few messages of varying quality. The message with the least quality overall is anything that’s been crowdsourced to include language. Because ESL speakers struggle to be ESL speakers because English is an especially labyrinthine language. Even constructed languages like Esperanto need for the speaker to have a basis in the Romance language family to have that first little foothold in understanding the wider language. Even with an accompanying Rosetta stone, the time and effort to extract the language may not be sent to the “right” audience. For instance, a hyper-intelligent space-octopus may never make sense of letters, but a series of prime number beeps may “speak” more to them. If they can hear. Or see. Or anything.

And if we can’t teach prairie dogs Esperanto, why are we sending space octopuses on a tidally locked, maybe-planet around a dim star messages about Doritos?

While crowdsourcing space messages engages youth to think about space and aliens and science and physics, it doesn’t encourage them to approach it critically. Critical thinking is what separates science from superstition. Lightning came from the gods before we had enough sense to know that it came from accumulated static electricity in clouds. Yes. Thor is a much cooler explanation, I get it.

But I guess “Send the aliens your math homework” isn’t that much fun, especially if you suck at your math homework, like most American kids do compared to other nations. Like I did from ages 12 to 23, and probably still do at any advanced level.

So let’s say that there’s no message to decode. Instead, there’s a language to decode. We’re finding ourselves in the world of Ted Chiang’s “The Story of Your Life,” in which a linguist interweaves the story of her daughter’s life with the story of her meeting a group of aliens that come to be known as heptapods for their bizarre, radially symmetric physical shape. The aliens talk in something that at first is indiscernible as language, compared at first to a wet dog shaking water out of its fur.

Eventually, the linguist is able to begin communicating on some basic level, learning the language of the heptapods by isolating particular variances in the sounds, learning the words. Except then she realizes that there’s no order to the way they speak their sentences.

Then there’s the writing — the language that comes to be known as Heptapod B. It has a particular order, and almost a rhythmic calligraphy to how its written. It also bears little relationship to Heptapod A, the spoken language of the species, and reveals a sort of philosophical underpinning of the heptapods. Nothing can be left out of the written language. But when they write it, there’s also a strange conceit — the entire meaning of the sentence had to be grasped before it could be written. This kind of thinking also informs the emphasis of their mathematics and, as it turns out, their worldview. This has echoes of Slaughterhouse Five, in that the heptapods already know how things are going to happen because time is illusory and depends on the point of view of the observer.

As she further decodes both languages, the linguist finds herself thrust into taking on this unique heptapod worldview, and her own thoughts take on this progression that only appears nonlinear to our thinking, but is perfectly linear to heptapods.

Imagine trying to decode that without a native Heptapod A speaker present. Squiggles, lines, communications coming in by radio signal. And with a wide ranging difference in their math, calculus and physics — where we can both be right, but put our emphasis on different places to the point where we can appear to be writing down two separate things — and we have to question if we could even do something so straight forward as the scenario presented in Sagan’s Contact. It is impossible.

We must, at least, consider a worst case scenario. In The Sparrow, by Maria Doria Russell, humanity gets a signal from Alpha Centauri. A group of Jesuits rush to build a craft that can take a crew to the planet, following the content of the message: the most beautiful music humanity has ever heard. The novel progresses in a nonlinear fashion. The entire time, we know that only one occupant of the craft survives to tell the story.

The Jesuits arrive. There are in fact two species on the planet, both intelligent, but one much more primitive. That’s the Runa. They’re basically Centauri foragers. Then there’s the ruling class, the Jana’ata. They’re the ones who sent the message originally. The humans teach the Runa agriculture, and everything goes south, because we’re talking about oligarchs having their rule threatened. Most of the crew is murdered in the ensuing rebellion. Except for the lone survivor, Sandoz — he’s taken into slavery by the Jana’ata, and bound over to the source of the signal, a poet and songwriter on the planet.

Sandoz is disfigured, in keeping with a tradition of the Jana’ata in which there is no greater dignity than reliance on others; he is rendered more or less helpless by the disfigurement of his hands. The next step involves the poet repeatedly raping Sandoz, then having his friends do much the same. These conquests are then written into song and broadcast: the exact nature of the songs we hear at the beginning.

So there are a number of missteps in the way contact is handled with the other species, and very, very bad things happen as a result.

To make plans to deal with any actual aliens, we’re going to ignore the people who believe in the Majestic 12, Roswell crash and other related ephemeral UFO culture — those who think that we have made face-to-face contact with intelligent alien species already. (We will also ignore their suspicions that the aliens hate us and want us to be genetic guinea pigs as well.) The “true story” of aliens is ridiculous sci-fi posing as reality, and eventually Aryan aliens step into the picture.

Instead we have a real-world problem. We’ve tried sending our language directly, more or less. This method isn’t going to work because we’re not sending a Rosetta stone, and besides, the Rosetta stone’s other points of reference were languages we already knew. And, short of being heptapods, we won’t already know their language in advance. We’ve tried sending math, and music, and pictures. With any luck, these messages haven’t reached anyone, anyones, or any things. We need to do better. If we can’t even send out a decent first message, how are we ever going to handle face-to-face interaction without a catastrophe?

John Wenz is a writer living in Philadelphia.