I Am An Object Of Internet Ridicule, Ask Me Anything

by C. D. Hermelin

I moved to New York City, and I needed to make money. I wasn’t having luck getting a job. It’s a common tale.

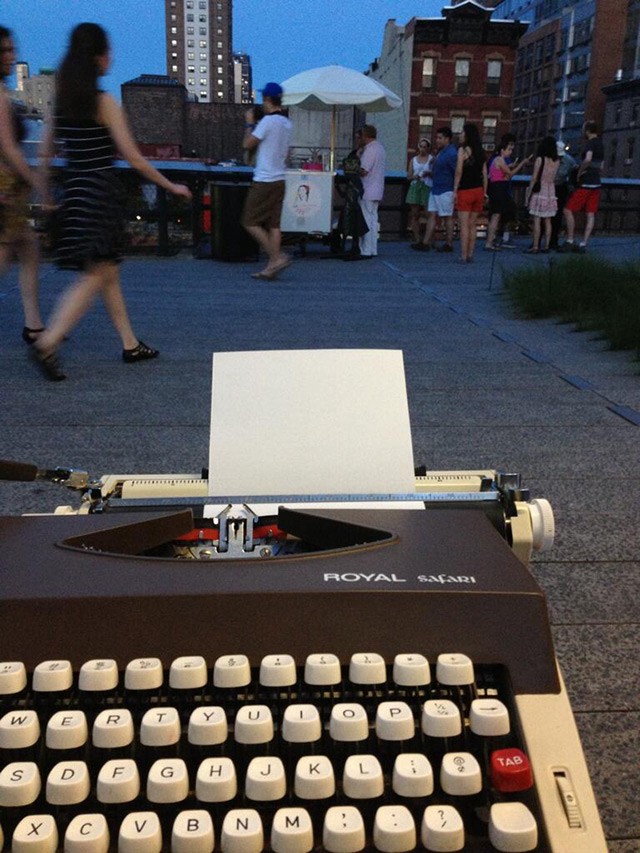

My solution was to grab my typewriter that I bought at a yard sale for 10 dollars and bring it to a park. I’d write stories for people, on the spot — I wouldn’t set a price. People could pay me whatever they wanted. I knew that I had the gift of writing creatively, very quickly, and my anachronistic typewriter (and explanatory sign) would be enough to catch the eye of passersby. Someone might want something specific; they might just want a story straight from my imagination. I was prepared for either situation.

I started at Washington Square Park. My cousin joined, which was particularly nice, since it started raining and he held an umbrella over my head. Barely anyone stopped, but there was a grand piano player and dancers to contend with. So I tried the 5th and 59th street entrance to Central Park, and was lost among the Statues of Liberty, the bubble guys, the magicians, the stand-up comic, the free hugs guy, the jugglers. At the Hans Christian Andersen memorial statue, I was writing post-card size stories for grade schoolers, mostly in the vein of Pokémon and Disney. I didn’t make a lot of money — only enough money to grab a slice of pizza on the way home.

When I set up at the High Line, I had lines of people asking for stories. At seven to 10 minutes per a story, I had to tell people to leave and come back. It surprised me when they would do just that. I never had writer’s block, although sometimes I would stare off into space for the right word, and people watching would say, “Look! He’s thinking!” Writing is usually a lonely, solitary act. On the High Line with my typewriter, all the joy of creating narrative was infused with a performer’s high — people held their one-page flash fictions and read them and laughed and repeated lines and translated into their own languages, right in front of me. Perhaps other writers would have their nerves wracked by instant feedback on rough drafts, but all I could do was smile.

Each time I went, I’d walk home, my typewriter case full of singles, my fingers ink-stained. Lots of people were worried about copycats — what if I saw someone “stealing” my idea? I tried to soothe them. If every subway guitarist had fights about who came up with the idea to play an acoustic cover of John Lennon’s “Imagine,” the underground would be a violent place. More violent than it already is. Others, perhaps drawn by the sounds of the typewriter, would stop and just talk to me, watch me compose a story for someone else. Then they’d shake their head and tell me that the idea and the execution were “genius.”

Of course, the Internet could be counted on to take me down a peg.

I woke up one day not long after I started “Roving Typist” to a flurry of emails, Facebook posts, text messages and missed calls. A picture of me typewriting had made it to the front page of Reddit. For those who don’t know, being on the front page of Reddit is hallowed ground — the notoriety of being on the front page can launch careers, start dance crazes, inspire Hollywood. In other words, ending up on the front page of Reddit meant a decent chunk of the million-plus people who log on daily saw my picture.

Posted under the headline “Spotted on the Highline” was me.

It’s a pretty good picture, I thought. Although my shoes are beat up and missing their laces, my hands are frozen in a bizarre position, and that day was too hot for clothes that photograph well, I look deep in thought. Unfortunately, the two cute girls I was writing a story for are cropped out.

And so was my sign.

My sign said: “One-of-a-kind, unique Stories While You Wait. Sliding Scale — Donate What You Can!”

Without the sign, without the context, I definitely look like someone who is a bit insane. That’s how I thought of it, before I clicked to look at the hundreds of replies; I figured people were probably wondering why I would bring my typewriter to a park. And when I started reading the comments, I saw most people had already decided that I would bring my typewriter to the park because I’m a “fucking hipster.” Someone with the user handle “S2011” summed up the thoughts of the hive mind in 7 words: “Get the fuck out of my city.”

Illmatic707 chimed in: I have never wanted to fist fight someone so badly in my entire life.

Leoatneca replied: Bet 90% of his high school did to. It’s because of these guys that bullying is so hard to stop.

There were hundreds more. A few people were my staunch defenders, asking the more trenchant commenters why they cared so much. Others started to wax nostalgic about their own typewriters. But the overwhelming negativity towards me, and the “hipster scum” I represented, was enough to make me get up from my computer, my heart racing, my hands shaking with adrenaline.

As a member of the first generation to freely and gladly share my pictures, videos and thoughts online, I’d always — until now, anyway — adopted a “What’s the worst that could happen?” attitude, mixed with an “Everyone else is doing it!” mentality towards my online presence. Many of the best things in my life couldn’t have happened without sharing these pieces of myself online — meeting favorite authors at bars thanks to Twitter, getting another chance at a lost crush thanks to Facebook. And yet, I still felt thrown when I was presented with an image of myself that I couldn’t control. Yes, I know that I am pretty much always being watched (especially at a beautiful tourist attraction in New York City, doing something partly designed to attract attention) but that didn’t prepare for me for the reality of seeing myself taken out of context.

I did worry, when I started typewriting, that my stories would make it online somehow, and they would be ripped to shreds by literary, high-minded commenters. In this unrealistic dream world, I was going to defend their quick composition, their status as literary souvenirs of the city, the difficulty in writing a story while the person who is paying you looks over your shoulder, and another two or three people ask you questions while kids are asking if they can “just press one key.”

Of course I sat back down. Of course I read every single comment. I did not ready myself mentally for a barrage of hipster-hating Internet commenters critiquing me for everything: my pale skin, my outfit, my hair, my typing style, my glasses. An entire sub-thread was devoted to whether or not I had shaved legs. It was not the first time I had been labeled a “hipster.” I often wear tight jeans, big plastic-frame glasses, shirts bought at thrift stores. I listen to Vampire Weekend, understand and laugh at the references in “Portlandia.” I own and listen to vintage vinyl. The label never bothered me on its own. But with each successive violent response to the picture of me, I realized that hipsters weren’t considered a comically benign undercurrent of society. Instead, it seemed like Redditors saw hipsters and their ilk as a disease, and I was up on display as an example of depraved behavior.

The most positive comments were the ones where I was compared to famous people — ”Doctor Who”’s David Tennant was one, the heart-of-gold porn star James Deen was another. I took the bait, eventually, and commented myself. I explained that it was me, that I was not just bringing my typewriter to the High Line for the hell of it — it’s pretty heavy, for one, and for two, I don’t really like writing outside. I explained that I was writing stories for people. In my explanation of my cause, it became just that — a “cause.” I knew, from the smiles on people’s faces when they saw me out typing, that I was out in the world as a positive, day-brightening entity. Bashing me was like hating on an ice cream truck.

Luckily, people agreed with me. After I posted, the message board thread’s climate changed immediately. Not unlike real life, people were complimentary and kind. Many people deleted their mean comments — one person was so embarrassed for threatening to smash my typewriter that he apologized to me, and then went through and started trying to make other haters apologize.

My favorite exchange was between “I_thrive_on_apathy” and “dlins”:

i_thrive_on_apathy: What the fuck is he going to do with that typed page? Scan it?

Dlins: you do realize things have value even if they’re not digitized, right?

i_thrive_on_apathy: Huh?

The reaction, then, had nothing to do with hipsters. It was a hatred of people that need to stand out for standing-out’s sake. That realization was at once positive and negative — people didn’t hate me because I was a hipster, they hated me because I looked like I was nakedly desperate for attention, and had gone about that attention-grabbing by glomming on to marginalized trends.

It only took about 12 hours from when I saw the thread and commented for people to stop commenting almost completely. The post quickly disappeared from the front page. To tell the truth, I was disappointed. I thought something might come of it — a real job, maybe. What better proof is there for me to show that I have that go-getter’s attitude? Instead, my moment of Internet notoriety disappeared.

I thought.

Reddit’s community has never seen an image they couldn’t write all over using white Impact font and re-post, and only a few days afterwards, someone had appropriated the picture of me and wrote, “You’re not a real hipster until you’ve taken a typewriter to the park” in giant white letters in the unused space above and below my body. Another torrent of meanness followed on that thread, although many Redditors with good memories came to my defense.

Now that the meme was created, with content ready-made, it was taken from Reddit and re-posted all over the Internet. It was “pinned” over 30,000 times on Pinterest, the folks at 9gag shared it on their various personal Facebook pages nearly 9,000 times. I was awarded the “Look at Me!” award for October 2012 from “diehipster dot com.” Well-meaning friends took screenshots of Tumblr, Instagram, and Twitter anytime they saw the picture posted or mentioned. I had gone from Reddit curiosity to “Internet meme.” My ex-girlfriend texted to ask if I was okay. My parents finally saw it. My dad didn’t know why I had dressed “funny.” My mom was understandably worried for me, flashing back to the times I was bullied in high school. I knew it made her feel powerless, just like it used to feel when I came home early from school because someone threatened to pull a knife on me. Now, it was dozens of someones — faceless and impossible to control.

At lunch with a friend who was trying to get her web series off the ground, she asked me how I was dealing. “Okay,” I said, “I think it would bother me more if people weren’t so complimentary in real life.” Thinking about her own troubles in creating something viral, she remarked, “It’s too bad you can’t figure out a way to exploit this somehow.” Other than sometimes posting my Twitter handle on pages where I saw the picture, I couldn’t do much. Part of me wanted to ignore it all, dismiss it like a pop-up blocker dismisses fake contest possibilities. Still, for every hateful comment online, there was a real person who picked up a short story and promised to buy a novel, if/when I wrote one.

But the vain part of me wanted to make sure the entire world knew that I wasn’t asking for attention because of some base urge to be noticed and photographed. Instead, I wanted people to know that I was nice, approachable, and able to write pretty good short stories really quickly. And that my wardrobe was more a function of my budget than hipster assimilation.

Even after that deluge, nothing happened — the Internet has both a long memory and the attention of a goldfish. I had been cast aside for a far cuter hipster puppy. I knew that the Internet is also a content recycling machine, but that each time the picture showed up now was more like the last couple kernels of popcorn popping after the microwave is turned off.

I was surprised when my ex-girlfriend called me to talk about the meme. “Would you mind if I wrote an article about this for xoJane?” The website she referred to had a series of essays they dubbed “It Happened To Me” that they sprinkled in amongst feminist-leaning news and features. “I want to talk about how all of this makes me feel. You, all over the Internet, right after you dumped me.”

We had only been broken up for about a month and a half after having been together for two years. I knew that she was still hurting, and I still felt — still feel — guilty for hurting her. I thought that perhaps it was going to be good to excise some demons.

I asked how much they paid (very little) and if she would let me read a draft before she sent it to her editor. She said yes. I was surprised to realize that people in my life were being affected by this negligible level of Internet celebrity. In the meantime, I had started a real person job at a leasing office, and my MFA program in creative writing at the New School. I didn’t have time to go out and type. Some people in the program recognized me from the Internet. Once or twice, someone stopped and asked if I was “that typewriter guy.” I felt secure in the knowledge that whatever my ex wrote, I would be fine.

Even though she didn’t end up showing it to me before it was published, her article — “It Happened to Me: I Got Dumped By A Meme” — wasn’t mean-spirited. In fact, it was sweet — she barely talked about our time together, and when she did, it was fond. The article instead focused on the fact that even though she had unfriended and blocked me on every social media outlet she could find, I was still around, posted to her Facebook page, dragged through the mud on forums. She ended the piece:

“I hope this meme fades as quickly as it appeared. For my sake, and for The Ex, I hope that the Internet’s hive mind soon finds another hipster target to jab. Finally, I hope that my next boyfriend is Amish, because it seems way easier to avoid those guys online.”

Unfortunately, her article ended up casting me in the same light that the picture did — she never explained that I was busking with my typewriter, and the comments section blew up all over again. Because I had broken up with her, the army of xoJane commenters were especially nasty. JaneJaneJane wrote, “He looks like a dong and there are 1,000 more jagbags like him that you’d have to weed through in NYC before you find a cool, real-deal fella. Not to make light of your heartbreak, but consider yourself lucky. Seriously. What an assdweller.”

The top-rated comment, by someone who called themselves “Rutabaga,” went, “Sounds like you dodged a bullet to me. My first thought seeing that picture is that he looks absolutely insufferable.” My ex accidentally posted my personal Twitter, which has links to my website, writing and LinkedIn account. All were fodder for ridicule. She called to apologize, and I ranted back to her, mad that she hadn’t sent me the article so I could have at least been painted in a completely true light. Again, I went down into the comment rabbit hole, but the climate didn’t change like before. My intended typewriter mission didn’t matter to this crew — what mattered was I broke the author’s heart. I wasn’t going to change minds, so I closed the tab, and I tried not to think about it.

The day after the first, un-memeified picture was posted to Reddit, I went out with my typewriter, very nervous. I tweeted on my “@rovingtypist” Twitter account that Redditors should stop by, say hello, talk about the post if they wanted. Someone responded immediately, told me that I should watch out for bullies — the message itself was more creepy than he probably meant it to be. I was nervous for nothing; a few Redditors came out, took pictures with me, grabbed a story. I was mostly finished for the evening when Carla showed up — Carla was the Brazilian tourist who took the picture of me and put it up onto Reddit. She was sweet and apologetic for the outpouring of hate, as bewildered by it as I was. She took a story as well, although I can’t remember what it was about. I messaged her when I first saw the picture posted with the meme text, letting her know that her picture had been appropriated. “I’m not concerned about it,” she said.

Hers was the position to take, and one I should have adopted earlier.

For all the hateful words that were lobbed at me, it barely ever bubbled over from the world of online forums and websites. I received zero angry emails, only a few mean tweets. My Facebook was never broken into and vandalized — my typewriter remains unsmashed, no one has ever threatened violence towards me in real life. Instead, there are these pockets of the web that are small and ignorable, filled with hate for a picture of me, for this idea of a hipster — for the audacity of bringing a typewriter to a park.

A few months later, when Christy Wampole wrote an essay for the New York Times bemoaning hipsters and their devotion to irony, I couldn’t help but feel empathy for all those tossed onto the web as pitiful avatars of hipsterdom. Wampole had inadvertently joined the ranks of Internet commenters who make vast, sweeping judgments based on careless observation. It was a strange experience to watch the Internet’s vitriol encapsulated as a call to action — a call for dismissal, really — from the New York Times. When I hear someone labeled as a “hipster,” I make sure to have the opposite response. I take a second look. What Wampole, and a whirlwind of Internet commenters don’t understand is, usually, the hipster label is a compliment, a devotion to a self-evident truth.

Originally, it felt silly labeling my venture a “cause” while I defended myself to an anonymous horde — but now it feels anything but. The experience of being labeled and then cast aside made me realize that what many people call “hipsterism” or, what they perceive as a slavish devotion to irony, are often in fact just forms of extreme, radical sincerity. I think of Brooklyn-based “hipster” brand Mast Brothers Chocolate, which uses an old-fashioned schooner to retrieve their cacao beans, because the energy is cleaner, because they think that’s how it should be done. I think of the legions of Etsy-type handmade artist shops, of people who couldn’t make money in their profession, so found a way to make money with their art.

While I hung up my typewriter keys and stationery for the winter (typing inside is fairly loud — how did they focus on anything back in the 60s?), this summer I’ve started going back out once a week. People are as complimentary and delighted as ever. No one has mentioned the meme to me yet, although it still lives its own life; BuzzFeed used it a few months ago in a series of pictures that promised to make you “black out with rage.” I try not to click when I see that someone, somewhere, has found it again. I prefer to let these little cesspools of cyberspace fester and then stagnate, forgotten as they should be, secure in the knowledge that I am doing something that matters to me.

C.D. Hermelin is a 26-year-old writer living in Brooklyn. He is on Twitter.