The Olds Don't Know Where Facebook Is

by Becca Hafter

My mom is always saying things like “Oh, Theresa, oh no, I don’t think she is on Facebook.” Or, “All of my college friends have thankfully joined Facebook!” and it drives me crazy because Facebook is a noun that you possess, not a noun with which you engage. The word “Facebook” requires an indefinite article (a, an) or a possessive adjective (my, hers), not a preposition (on, in, above).

• “All of my friends have a Facebook.”

• “No, he’s too cool for Facebook, he doesn’t have a Facebook.”

• “She finally gave in and got a Facebook, but ugh, she restricts her viewable photos to profile pictures.”

I have tried to explain this grammatical distinction to my mother multiple times. She does not understand my argument. For her, Facebook is a website on which she interacts. It is a place over there. She must locate her self in relation to Facebook, a separate sphere from her ordinary existence. To me, “posting” or “liking” instantly connotes Facebook; she needs a preposition to explain to her audience where her “posting” or “liking” action took place. Her online presence occurs on specific forums and in specific places, spaces that must be explained. But that is so annoying!

Being on Facebook means currently using Facebook, being on Facebook messenger or actively engaging with the site in another way. If I am logged into Facebook chat, I might say that I’m “on Facebook.” The preposition is necessary to draw notice to the extra layer of Internet space that I am occupying. Because, duh, I am always on the Internet, but I am not always actively engaging in the Internet. For millennials, a generational descriptor which we are tasked with reclaiming, Facebook is the assumed space in which life occurs. Millennials do not need to use a preposition in conjuction with Facebook because the space is naturalized. My assumed existence is on the Internet and using Facebook. My Facebook. Which is the other grammatical issue at stake: possessive adjectives.

The difference in language expression stems from whether one has a sense of owning her Internet presence. We’re always talking about “my” Facebook and “my” Twitter and “my” Instagram. We “have” Vines and Tumblrs, too. (Tumblr is always “my Tumblr,” though of course Tumblr also sees its Tumblr fragments as individual Tumblrs, which are prone to decoration and remodeling in a way that Facebook is not. Twitter is the middle space on that continuum.) We verbally conceptualize our Internet presences as extensions of our physical possessions. When friends need to log onto their Facebooks on my computer, I ask them to open a tab in an incognito window. I might say: “My Facebook is open, don’t log me out.” Their slice of the Internet can’t supersede mine. Their Facebook and my Facebook can and should lay side to side, each contained in its own window. His Facebook. Her Facebook. Our Facebooks.

But Olds don’t have Facebooks. They’re “on” Facebook. The Olds need a preposition when they talk about Facebook because they do not automatically locate themselves on the Internet. But their word choice serves an additional function. Their constant verbal reification of operating in (on) a space that is not theirs but Facebook’s works pretty well to keep themselves aware of the fact that Facebook owns everything they post. This is something millennials love to disregard.

Even if the grownups know better about privacy and property rights, their grammar is still wrong.

The website Facebook has its roots in a physical college face book, a publication dating from at least 1983 in which freshman would have pictures for their peers and upperclassmen to judge. College face books were like high school yearbooks, but less well-intentioned. As college face books and high school yearbooks serve basically the same function, and college face books have the same name as Facebook and in my experience, the Olds are easily confused by this argument, let’s think about face books and Facebook like yearbooks. You would never be on a yearbook, you would have a yearbook. Your picture might be on a yearbook page, but the page and book themselves are nouns that need to be possessed, not modified with prepositions. You can have a yearbook. You can open up your yearbook to your yearbook page. You can check your yearbook page in your yearbook for your senior quote. Yearbooks and yearbooks pages get indefinite articles or possessive adjectives, just like Facebooks and Facebook profiles.

Unfortunately, for the Olds, these days the word “profile” is only implied after Facebook. People used to have Facebook profiles, but as Facebook rolled out more and shinier updates, this verbal reminder of the physical forebear of Facebook was phased out. The Olds are confused about proper Facebook grammar because they joined Facebook after profiles had disappeared. Prior to 2005, no one who was not a college student could have a Facebook. Prior to mid-2006, no one who was not either a high school or college student could have a Facebook. The Facebook profile, as it was originally conceptualized, lost prominence in 2006 when the “newsfeed upon log-in” style was introduced. My mom, a fairly early adopter, did not get a Facebook until 2008, still too late to have interacted with the original Facebook profile. (A telling description, packed with possessive determiners, of Facebook in 2007: “This was the era when your wall became a central component for your social life.”)

The Olds are missing the grammatical roots of Facebook content. They never experienced Facebook profiles that they could call their own. It’s not their fault that Facebook dropped the “profile” way before the Olds started oversharing about their Zumba classes on our newsfeeds.

So the Olds, usually right about grammar and using dictionaries and how to best clean your oven after dripping chicken fat all over the grate, are wrong about this one. And they should be, too! The Internet is the domain of millennials. Within the online universe, we have carved out places we call our own, places that we posses. These, of course, may be places where only we have the knowledge of the grammatical roots of the site. Millennials exist in a world where Facebook, and the Internet in general, is the unspoken medium in which we live our lives. Let the millennials win this one, Olds. You rarely let us win anything else.

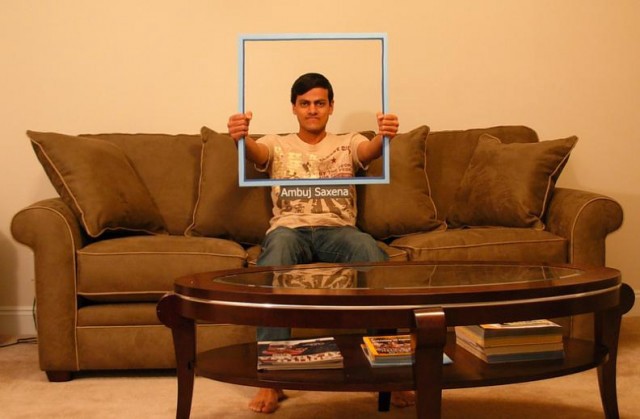

Becca Hafter is an Awl summer reporter. Photo by Ambuj Saxena.