The Ka-Ching Zone

The quasi-hypnotic effects of certain Internet activities were discussed by Alexis Madrigal in The Atlantic recently: “The Machine Zone: This Is Where You Go When You Just Can’t Stop Looking At Pictures On Facebook.” In particular, Madrigal drew serious attention, at last, to the elephant in the room: people may spend hours a day demonstrating compulsive “engagement” on Facebook or Tumblr, but they very commonly loathe themselves for doing so:

Silicon Valley has made the case to itself (and to the users of its software) that we are voting with our clicks. […] Of course, that completely elides the role the company itself plays in shaping user behavior to increase consumption. And it ignores that people sometimes (often?) do things to themselves that they don’t like.

Madrigal goes on to compare the lure of these time-sucking pastimes — in particular, clicking through photographs on Facebook — to the similarly hypnotic and addictive appeal of slot machines, citing MIT anthropologist and researcher Natasha Schüll’s name for the trancelike state sought by slot-machine gamblers: “the machine zone.”

What is the machine zone? It’s a rhythm. It’s a response to a fine-tuned feedback loop. It’s a powerful space-time distortion. You hit a button. Something happens. You hit it again. Something similar, but not exactly the same happens. Maybe you win, maybe you don’t. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

This does sound uncannily like obsessive Internet use. Do the designers and purveyors of these addictive products, whether they are slot machines or LOLcat galleries, have an ethical responsibility to protect users from the consequences of their own compulsions?

Schüll talks about one [slot machine] designer, Randy Adams. At first, he tells her that he’s “morally” opposed to [designing] machines that enable compulsive behavior, which is an acknowledgement that it’s possible to do so. […] When pressed to specify ‘the part that turns it from fun into addiction,’ he replied: ‘It’s the design of the game,” and then added that this characteristic of design was “not intentional on our part, just the way it happened to evolve.’”

Related: The Tetris Effect

The designer is, perhaps unsurprisingly, disinclined to confront the fact that he is complicit in contributing to the addictive potential of the game. The truth is actually something worse: he’s almost certainly been hired explicitly to exploit and enhance the addictive potential of the game.

As a thought experiment, imagine there were incontrovertible proof that certain web service designs caused people to enter the machine zone, quadrupling time on site for a subset of users. Would designers outlaw their use or would they all deploy the tricks for their startups?

[Can this be a serious question?]

Things could be different. A site could encourage a different ethic of consumption. To be a little absurd: Why not post a sign after someone has looked through 100 pictures that says, “Why not write a friend or family member a note instead?”

That isn’t “a little absurd,” Alexis Madrigal; that is XXL-absurd. We may fool ourselves that social media and slot machines are there to entertain us, “just for fun”; these are commercial products that exist solely to make money for their owners. With respect to the making of money, the evidence has long been limpidly clear: Silicon Valley entrepreneurs are no different from the most rapacious Gilded Age plutocrats, whom they exactly resemble in every particular excepting the moustaches (so far).

The function of a plutocrat is to increase profits by every available means. If software engineers have failed to comprehend exactly what it is they are enabling… well… their longstanding reputation as the flower of our intellectual meritocracy is thereby all too plainly called into question.

“[F]ighting the great nullness at the heart of these coercive loops should be one of the goals of technology design, use, and criticism”: here Madrigal makes an accurate and worthy observation. But on what planet has he observed that technologists are “more likely to be ideologues than craven financial triangulators”? Wearing a t-shirt to work doesn’t mean you are not The Man — or, to be more accurate, his obedient servant.

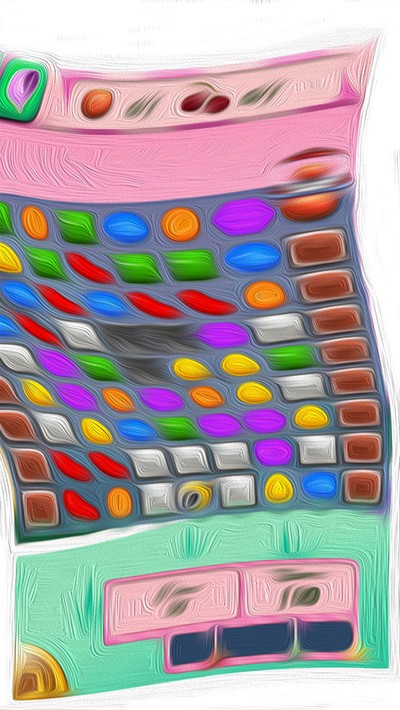

I can demonstrate this to you conclusively in three words: Candy Crush Saga.

This infernal game (in which I am currently trapped on level 97) is the ultimate slot machine that never pays out. It even looks and sounds quite like a slot machine: rows of colorful digitally clinking gewgaws that once in a while align and cascade in a bizarrely gratifying way, in response to minute commands from the player. The sounds this game makes are both hellishly unpleasant and profoundly, weirdly pleasant. Candy Crush Saga is making its owners rich as Croesus, and not by accident.

Professional game designer Andrea Phillips wrote recently on the similarity between gaming addiction and gambling addiction:

[A]t least some game developers are intentionally trying to induce addictive behaviors, without question. It’s common for a game design spec to talk about making a game “more addictive” in positive terms, as shorthand for “highly engaging and fun to play.” There’s also rampant and intentional use of the compulsion loop, which is a term ultimately derived from Skinnerian psychology: You train a rat that something nice will happen when it presses the lever, in order to get it to keep pushing that lever again and again. […]

It’s that tension of knowing you might get the treat, but not knowing exactly when, that keeps you playing. The player develops an unshakeable faith, after a while, that THIS will be the time I hit it big. THIS is the time it will all pay off, no matter how many times it hasn’t so far. Just one more turn. One more minute. But it’s really never just one more.

It is possible to play Candy Crush for free, but make no mistake, the game is a cash-generating proposition. The difficulty of the game escalates as you make your way through, but pay one dollar and be granted just enough moves or special candies to clear a level. Or pay one dollar simply to keep playing: five plays right now, rather than having to wait a few hours for five free ones. It takes a certain slight discipline to resist the bait. It’s just a buck! Less than a coffee, the hapless player might think.

Megan Rose Dickey, a writer at Business Insider, recently admitted that she’d spent $127.41 in a single week playing Candy Crush. (Even I, a hardened skinflint when it comes to games, and to tech in general, dropped around $15 before wising up.) And Dickey and I are not alone. Despite its status there as a “free app,” Think Gaming has estimated that Candy Crush Saga generates over $630,000 per day. (This is the tip of the candy-colored iceberg; there are games, even those aimed at children, which have in-game purchases in amounts of $10 and $20 and more; Apple just agreed to a “parental gate” after settling a class action suit over in-app purchases.)

Understanding how people work is one thing. The latest round of intriguing and/or menacing developments in technology is eye-tracking. “FocusAssist” is a product designed to turn off courses when the user diverts his eyes from his iPad training. While more elegant than the forced waiting time of online courses today, it’s notable that this is promoted as a feature of new Samsung phones as well. Whatever use will they make of us with that!

I don’t have anything against capitalism, so long as it is practiced in a principled manner, and honestly. But I don’t care to be B.F. Skinnered into parting with my hard-earned pistoles. Can anyone doubt that the slot-machine-like nature of gaming now is the result of a deliberate strategy — or imagine for an instant that any profit-making entity will willingly concern itself with anything but profit, no matter the cost to its customers? This is inescapable. It’s the compulsion loop of the plutocracy.

Maria Bustillos is a journalist and critic in Los Angeles.