The Excellent Jewish Propagandist

Hello, would you like to buy something weird? Hammer Time is our guide to things that are for sale at auction: fantastic, consequential and freakishly grotesque archival treasures that appear in public for just a brief moment, most likely never to be seen again.

Arthur Szyk illustrated everything from “Mother Goose” books to Esquire magazine covers, from Coca-Cola ads to one of the world’s most beautiful Haggadot — but much of that was just a job. “I am but a Jew praying in art,” Szyk once wrote. He arrived in the United States — having fled Russian-occupied Poland for France, and then London — during World War II, where his ubiquitous caricatures of the Axis powers were favored by the media and government alike.

Szyk — pronounced shik — was one of many war-time propaganda artists, but his focus on war-time enemies set him apart. While others drew patriotic images celebrating nationalism and valiant soldiers, Szyk took aim at the Axis powers, with a particular focus on their militarist, pernicious leaders.

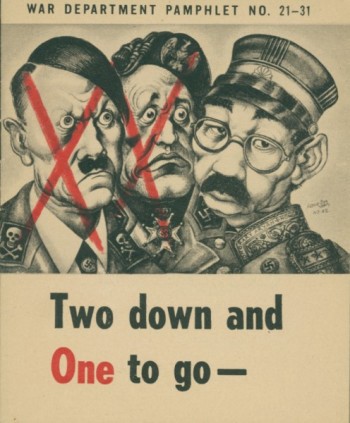

“Two Down and One to Go,” Szyk’s caricature of Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler, and Hideki Tōjō, became an increasingly circulated image as the Axis powers crumbled in Europe. It featured an “x” over the faces of Mussolini and Hitler, effectively depicting the stages of war to a population whose resolve, the military feared, had been enervated by Allied victories.

The war in Europe drew to a close, and homesick troops bypassing America for the Pacific front were in desperate need of a morale boost. Filmmaker Frank Capra, who was tasked with reminding soldiers “why the hell they’re in uniform,” was inspired by “Two Down and One to Go,” which appeared on the cover of War Department Pamphlet No. 21–31. In collaboration with Henry Stimson, the Secretary of War under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Capra soon released a short film under the same name.

The War Department circulated the film with two goals, both characteristic of wartime propaganda: to reinforce the righteousness of the cause and to demonize opponents.

Army Chief of Staff George Marshall, who narrates the film, is shown intermittently between a barrage of animated graphics and stock footage. After a swastika is exploded over Germany, Szyk’s “Two Down and One to Go” illustration appears. Tōjō remains defiantly untouched.

“Now that the United Nations has delivered Europe to the masses, two of our three enemies lie among the ruins of their own evil ambitions,” Marshall explains. He emphasizes the need to start in Europe, where supply lines were shorter, but that an invasion of Japan is by no means a disparate campaign, but rather part of “one global war.”

According to Marshall, the main impediment to a war simultaneously fought in Europe and Japan, or one that began in Japan, had been Pearl Harbor — the point being to remind viewers that Japan was a warmongering country. When the Japanese dropped bombs on the United States Naval Base in Hawaii, they did damage to an American fleet that, according to Marshall, would have been integral in launching an early offensive: “In England, we had bases from which to launch our fast growing air power, but in the Pacific, we had no air bases near Japan, and no strong allies, however brave.”

Onscreen, a stylized searchlight quickly extends from England to Germany, overtaking the giant swastika before moving across the Pacific, only to hover in the direction of Japan. Had the Americans instead focused on Japan — and defeated it, of course — they might have found Russia and Britain defeated by the Germans, perhaps too strong for even an American attack. The real end to the war, the film eventually explains, comes when the Japanese military is “completely crushed.”

Szyk’s “Two Down and One to Go” print, the cover of a U.S. Army booklet, was just part of a lot for auction at the Kedem Auction House in Jerusalem. The opening price of $600 included the pamphlet, additional caricatures, two signed checks, a single leaf depicting the Warsaw Ghetto uprising, an invitation to one of his exhibits in Philadelphia, and anti-Nazi Shabbat candles.

After the war, he produced radical work on wide array of topics — and, shortly after the founding of Israel and receiving American citizenship, was then investigated by the House Un-American Activities Committee shortly before his death. This film, produced by the Arthur Szyk Society, discusses the greater body of his work.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2NF5vU0fkrE

Alexis Coe’s work has appeared in the Atlantic, Slate, The Millions, The Hairpin, SF Weekly, The Toast, and other publications. She holds an MA in history, and was a research curator at the New York Public Library. Follow her. Image courtesy of Kedem Auction House, Israel.