House Ghosts

by Rachel Monroe

1.

The day my friends and I moved into the warehouse, we found cat shit in the corners and a cat skeleton in the sub-basement. The former tenant’s graffiti tags covered every conceivable surface, and the anarchists who lived upstairs made strange sounds, rendered uninterpretable by their floorboards, our ceiling. Whenever they dropped a heavy object (what were they doing up there?), a fine film of dust drifted down onto our heads. The door of my new room was red, and someone had spray-painted it with dripping, silver letters: SLUT ROOM.

None of us had ever smudged a house before, but this one seemed in dire need of psychic cleansing. I don’t remember where we got the bundle of sage, only that once we’d lit it on fire and sent its sweet smoke spiraling up toward the ceiling (and the anarchists), we had no idea what to say. Eventually, Cricket mumbled some sort of hippie exorcism, a banishment of bad vibes. We were making space for ourselves, we thought. Out with the old, and in with the new.

2.

In 1989, New Yorker Jeffrey Stambovsky signed a contract on a $650,000 three-story Victorian house in Nyack, New York. He soon learned that the house had one major drawback that neither the seller nor the realtor had disclosed before he offered up the down payment: it was haunted. The house’s previous owner, Helen Ackley, was friendly with the ghosts, who preferred Revolutionary War outfits and occasionally gave her grandchildren gifts. Every morning, Ackley bragged to Reader’s Digest, she’d been woken up by some unseen force shaking her bed. When she had a week off for spring break, she asked the ghost to let her sleep in. The next morning the bed was undisturbed.

Upon learning of the haunting, Stambovsky sued Ackley and her real estate broker, seeing to cancel his contract on the house and recover his down payment. A lower court dismissed the action, and Stambovsky appealed. The New York State Supreme Court ruled that under the doctrine of caveat emptor (buyer beware), Stambovsky was not due damages. The court did, however, approve his request to cancel the sale, noting that Ackley had frequently and publicly discussed the house’s ghosts. “As a matter of law,” the court concluded, “the house is haunted.”

3.

Horror movie hauntings have a reassuring, if programmatic, narrative logic: torture or betrayal or abuse or an evil cult produces a ghost, which proceeds to traumatize anyone trying to share its space. Maybe it’s angry or maybe it just wants to be loved; in any case, the consequences are usually violent. But if you have ever seen a ghost — and 41 percent of Americans report that they have — it was most likely a very different experience. On the whole, the ghosts of daily life are less homicidal and more enigmatic than their horror movie counterparts. They hide the salt shakers and bother the cat. They flit by the door on rainy evenings, or stand by the bed with a sad look on their faces. It is unclear where they came from, and difficult to know what exactly it is that they want.

In his taxonomy of the ghosts of New York state, mid-twentieth century folklore scholar Louis C. Jones noted that “something more than a third of our ghosts died violent or sudden deaths,” implying that the majority died more quietly, in the traditional manner. (Perhaps, then, they have nothing major to avenge, and thus make for tolerable roommates.) The converse also appears to be true: famous murders don’t tend to produce famous ghosts. Nonetheless, most of us would prefer not to live in a house where a stranger has met a violent or tragic end. But why is that, exactly?

In research for her 1999 master’s thesis, folklore scholar Julia Kelso interviewed real estate agents, homeowners, and potential home buyers in order to determine how beliefs about death impacted actual or theoretical real estate purchases. Overwhelmingly — and unsurprisingly — she found that people expressed discomfort at the idea of living in a house where someone had died in a violent manner. They gave a variety of reasons: What if the murderer came back? What if the house was impossible to re-sell? More than any fear of tangible, physical consequences, though, Kelso’s interviewees chalked their unease up to bad vibes, bad energy, bad dreams: “I’m afraid I’d obsess about it, have bad dreams about it, get nervous when I was home alone at night,” one subject explained. “I don’t expect I’d ever have any physical trouble, except for what I caused myself with my own irrational fear. I know that the fear is irrational, but I also know I would have it.”

Most (but not all) were fine with the idea of living in a house where someone had died of natural causes. (One man, however, refused to live in a house where anyone had ever died of any reason; he tended to prefer new construction, he said. Because you just never know.) Accidents were upsetting to some, especially when children were involved, but on the whole they were less troubling than intentional deaths. Suicide-by-pills was less upsetting than than suicide-by-gun. And nearly everyone was bothered by murder.

Kelso chalks this up to superstitious uneasiness about “bad deaths.” If the ideal death occurs at home after a long, happy life, with one’s affairs put in order and one’s rosy-cheeked descendants surrounding the bed crying quietly while the priest administers last rites, a bad death is disruptive and sudden. Nothing is put in order; in fact, order is destroyed, as is any sense that the world is a predictable or benevolent place. In the Middle Ages, those who died out of turn were considered at least partly to blame for the circumstances of their deaths. Many religious burial traditions keep the bad dead away from their virtuous friends. We don’t want anyone getting any ideas.

Even those placid, rational Swedes were known to segregate their dead well into the 20th century. Burial place and method depended on the manner of death, whether it was public, quiet, shameful, or depraved:

“Public” funerals were the norm. “Quiet” funerals were for stillborn children, the unbaptized, people who had committed suicide in a fit of temper, alcoholics, and those who had given their bodies for anatomical research. The priest was present, but was allowed to read only the commitment. “Depraved” burials were for victims of duels, for anyone who had been killed in anger, died in prison, or lived an ungodly life, for murdered children, and for the unknown found dead. Their graves were situated in the “worst corner” of the graveyard, still seen in many churchyards today. The priest was not present and there was no Christian ceremony. “Shameful” burials were for deliberate suicides (who were excommunicated) and for the executed. Their bodies were buried in the forest. (Juha Pentikainen, The Dead Without Status)

“There’s a certain eerie feeling… if you know someone was brutally murdered on the floor, you know, and the blood was dripping there,” a real estate agent told Kelso. “The violence touches us in some way.” Even though it doesn’t, of course: There’s a confusion here, about where my body ends and someone else’s begins. Other people’s tragedies feel like a threat, and we prefer to avoid the contamination. Please, we say, I would prefer not to get that person’s bad death on me. I am afraid that it’s contagious.

4.

“If It were a bloody death — intentional or not — that would probably bother me,” another interviewee told Kelso. “Just the idea that they would probably never be able to get all of it up. For instance. even if it looks ‘clean,’ criminal investigators can still use luminol to detect the presence of blood, and it would still show up. The idea of a bodily fluid having been splattered all about bothers me regardless of the fluid. So in other words, suicide wouldn’t bother me unless it were particularly messy.”

Messy fluids, secret stains, blood that’s visible only under certain lights — even a house that appears ordinary may be splattered with all sorts of invisible contaminants, the physical or psychic residue that lingers long after any evidence has been scrubbed away. Think about it too hard and it can make you crazy: The room you’re in right now — someone else has lived there, maybe dozens of other people. Did they walk around naked, have sex on the kitchen counter, leave toenail clippings embedded deep in the floorboard cracks? Didn’t you read somewhere that dust is mostly dead skin cells? Their skin is piled in the corners, it’s getting on your dishes, it’s all over the floor! It’s enough to make you want to live alone in a brand new house and never open the door to anyone.

If normal strangers are bad, bloody strangers are worse: Courts have ruled that, even years after a crime, potential buyers should be notified if a house is marked by violence for fear that it remains invisibly tainted or stained or contaminated. Or stigmatized, which is actually the proper legal term for houses with substantial, non-physical damage. In the 1970s and 80s real estate law began moving away from a strict caveat emptor system, and began requiring brokers to disclose material defects such as insect infestations or nearby nuclear waste plants. By the late 1980s, some jurisdictions extended those protections, considering that houses could appear physically intact, but still be emotionally or psychologically damaged. Depending on the jurisdiction, “stigmatized properties” could include houses where people had killed themselves or been murdered; where Satanic rituals had taken place; or places with known ghosts. But violence was not the only thing that could invisibly mark a home, rendering it suspicious; in some jurisdictions, stigmatized properties also included places whose previous owners or tenants had been diagnosed with HIV.

I asked my mother, who’s an HIV/AIDS specialist, what it would take to catch the virus from a piece of property: “It’s physically impossible,” she said. “There is literally no way.” But mom! I said, and then came up with various bloody scenarios. But HIV is relatively wimpy, as far as viruses go, and doesn’t survive long outside the body. “Even if there was a mattress with a bunch of dried blood from an HIV-infected person soaked into it,” she said, “and you rubbed yourself on it, and you had an open wound, you still wouldn’t get HIV.” It’s actually more conceivable (though not probable) for hardier diseases, like tuberculosis or Hepatitis B, to be transmitted through household contact. (And even then, it’s people who are sharing the household, not people who live in the house years later, who are most at risk.) In other words, being afraid of getting HIV from your house makes even less sense than being afraid of being murdered by a ghost. (I know that the fear is irrational, but I also know I would have it.) Nonetheless, in 1989 the Texas legislature passed a law requiring brokers who had “actual knowledge” that a seller or former tenant had AIDS to disclose that information if a prospective buyer asked. (The question of what “actual knowledge” might consist of — a doctor’s note? local rumors? a really strong feeling? — was never resolved, as the federal Fair Housing Act’s provisions against housing discrimination nullified the Texas law.) No such provisions were made for other communicable diseases. Other states considered and enacted similar legislation, although none of it stuck for very long. Even now, although various privacy and anti-discrimination laws specifically prohibit the disclosure of HIV status, most casual definitions of “stigmatized property” mention murder, ghosts, and HIV infection, as if these are comparable things.

Perhaps, though, they are, in a way. As The Pagan Library helpfully points out, “You can potentially hurt yourself through your own fear much more than the ghost can hurt you.” Laws against house ghosts — like laws against house AIDS — didn’t safeguard anyone from actual harm; instead, the irrational fear of harm (which is not far removed from prejudice) was what the law protected.

5.

There is more than one way to clear a house (or a town, or a city) of its ghosts. Louis C. Jones thought there were three requirements for robust ghost lore: a place that’s been settled for a while (to provide the ghosts); housing stock that’s relatively old (to provide the haunted houses); and a somewhat stable population (to exchange and embellish the stories). Just-built suburbs may be frightening, but not because of hauntings; it takes some time to cultivate collective fear.

(This may also be why the empty strip malls and uninhabited housing developments of Florida and Arizona, those suburbs no one turned out to be able to afford, seem so sinister. They never had the chance to acquire their ghosts, and so they sit there quietly, horrifyingly unhaunted.)

So: to live ghost free, build brand-new houses and never talk to your neighbors. Depending on where you live, you may already be doing this, and perhaps it brings you peace of mind. But then again, peace of mind is overrated.

In The Gentrification of the Mind: Witness to a Lost Imagination, Sarah Schulman notes that the neighborhoods that had the highest rates of HIV infection in New York City in the 1980s became some of the city’s most gentrified neighborhoods twenty years later. A young dancer who lived in her building died of AIDS; after his death, his rent-controlled apartment jumped from $305 per month to $1,200. Meanwhile, the story of AIDS itself slowly became gentrified. Schulman describes her rage upon hearing a “clean-cut” NPR story about how Americans “came around” to accepting people with AIDS: “Now after all this death and all this pain and all this unbearable truth about persecution, suffering, and the indifference of the protected, Now, they’re going to pretend that naturally, normally things just happened to get better,” she seethes. But with the original inhabitants of that world gone — either dead or pushed to the margins by rising rents and relentless development — no one was around to argue otherwise. And so Schulman writes with the rage of a person who sees the dead who cluster on the sidewalks and cafes of their former neighborhoods, and the living who don’t even seem to notice: Watch out, she seems to be screaming: You’re walking right through him.

Gentrification, in Schulman’s formulation, turns out to be like the worst kind of spirit cleansing: rather than banishing the ugly past of a place through incense or holy water or ritual words, we simply raze their buildings and put up something sleeker and more expensive (or faux-artisanal but unghostly). Instead of ghost stories, the radio gives us uplifting bedtime narratives about how things were worse then, but are better now.

I have thought about this a lot and I am sorry I smudged the warehouse to chase out the spirits. I wouldn’t do it again. I can see no other choice but to take a radically pro-ghost position. And I think you should join me. Let’s spend some time with the quiet dead, and with angry or frightened or tragic dead, too. We can let them pass through our walls, accept their gifts. Maybe we’ll learn their stories and avenge their wrongs. At the very least, we can try to gaze upon their faces without fear. If we are lucky, someday maybe we will join them.

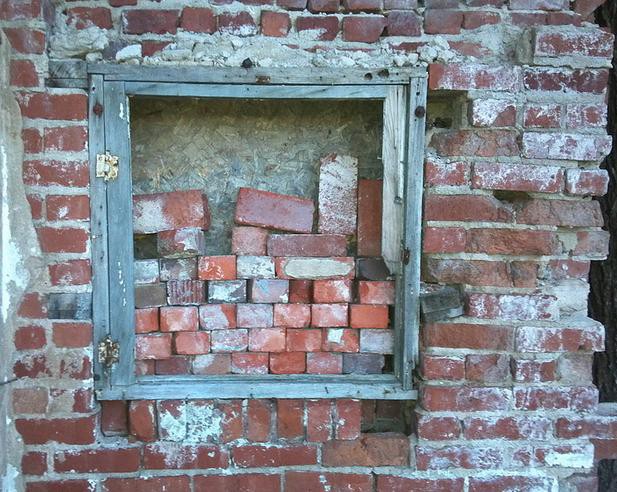

Rachel Monroe is a writer living in Marfa, Texas. East Village photo by Rex Brown. Propped-up house photo by Kurt Nordstrom. Contagion photo by Eneas De Troya. Condemned house photo by Megan O’Hara. Dumped items by Alan Stanton.