Eldridge Cleaver's Emo Diary

Hello, would you like to buy something weird? Hammer Time is our guide to things that are for sale at auction: fantastic, consequential and freakishly grotesque archival treasures that appear in public for just a brief moment, most likely never to be seen again.

Two days after Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, community leaders urged the nation to honor the pacifist leader with nonviolent gatherings. But among the vigils and demonstrations, riots also erupted in over 100 cities, although not in New York.

In Oakland, 15 members of the Black Panther Party parked their cars on Union Street, just a few blocks from where their leader had shot a police officer, and waited to be noticed. According to the Oakland Tribune, a patrol car soon pulled over to question them. The policeman riding in the passenger seat emerged first, and he was met with bullet. A shotgun shell grazed the driver, and 49 more bullets littered the cruiser.

“I will tell anyone that that was the first experience of freedom that I had,” Eldridge Cleaver, who was the group’s Minister of Information, told Henry Louis Gates, Jr. in a 1997 interview.

Backup was called, and the group disbanded. Cleaver and Bobby Hutton, the party’s first recruit, were among the eight men who sought refuge in a nearby house on 28th Street. Residents narrowly escaped as police arrived; a 90-minute gun battle ensued. The Oakland police launched round after round of tear gas through windows, and soon the house was in flames.

The fire forced them out, but what happened next is still debated. According to the police, Hutton emerged in a coat and was unresponsive to calls demanding he halt. Cleaver and eyewitnesses contend that Hutton not only halted, but responded to policemen’s suspicions that he was armed by stripping down to his underwear. Lieutenant Hilliard would later say that Hutton was handcuffed.

They just took Bobby and pushed him. They pushed him, and he only went about five feet. He was stumbling and almost falling. They shot him 12 times. Murdered him right on the spot. He fell down.

Hutton was 15 days shy of his 18th birthday. The Blank Panther Party’s first recruit was buried three days after Dr. King, six days after the shooting. By then, Cleaver was in jail, but more than 2,000 people attended Hutton’s funeral at the Ephesians Church of God in Christ in Berkeley. Marlon Brando and James Baldwin were there. Gloria Steinem, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Terry Southern, Norman Mailer, Susan Sontag and many others signed a letter about Hutton’s death to the New York Review of Books. At the time, The Black Panther Party asserted they had not planned the attack; Cleaver later said it was an ambush.

After the shooting, Cleaver faced up to 82 years in prison for violating parole. He spent his youth in and out of detention centers for petty crimes and a drug felony at the age of 18, but in 1958 he was convicted of rape and intent to murder. While in prison, he wrote Soul on Ice, an influential and celebrated work on race relations and black liberation ideology. The collections of essays was divided into four parts, and it is the first, “Letters from Prison,” that proves to be the most controversial. In it, Cleaver chronicles his transformation from marijuana dealer to rapist, the act of which he called “insurrectionary.”

I started out practicing on black girls in the ghetto where dark and vicious deeds appear not as aberrations or deviations from the norm, but as part of the sufficiency of the evil of a day. When I considered myself smooth enough, I crossed the tracks and sought out white prey. I did this consciously, deliberately, willfully, methodically…. It delighted me that I was defying and trampling upon the white man’s law, upon his system of values, and that I was defiling his women.

While he did renounce rape and his previous philosophy, he went on to write that “the blood of Vietnamese peasants had paid off all my debts.”

After he jumped his $50,000 bail, Cleaver relied on left-leaning countries and individuals to aid him. For seven years, he and wife Kathleen sought refuge first in Havana, and finally in France. Their son, Maceo, was born in Algeria, and daughter, Joju Younghi, in North Korea.

The Cleavers housed American psychologist Timothy Leary after the Weather Underground helped him escape from prison, but the two soon fell out. Cleaver placed Leary under “revolutionary arrest” after he continued to advocate for the use of psychedelic drugs.

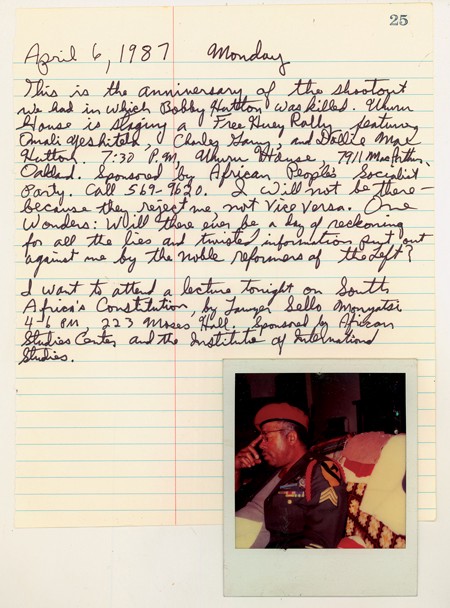

Cleaver also criticized Huey Newton, the co-founder of the Black Panther Party, who now believed guns were antithetical to greater goals for the black community. Cleaver argued that armed resistance was not an aggressive enough response to COINTELPRO, and urged Newton to adopt a policy of guerilla warfare. His position isolated him from the Black Panther party; Cleaver wrote, “One wonders: Will there ever be a day of reckoning for all the lies and twisted information put out against me by the noble reformers of the left?”

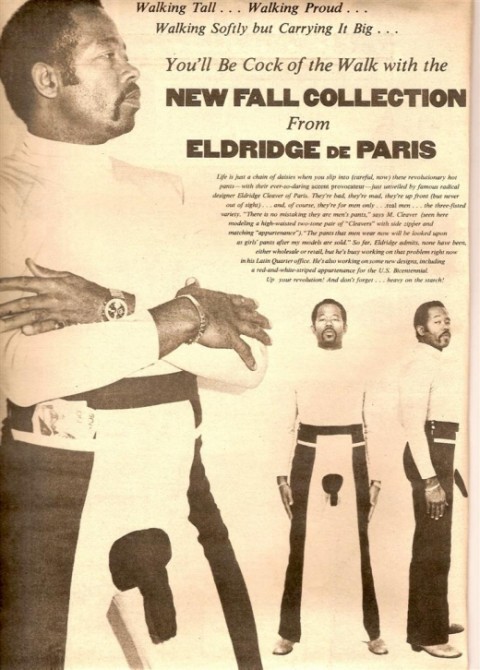

By the 1970s, Cleaver’s ideology dramatically shifted, as did his focus. He tried his hand at fashion design, creating a codpiece, which was basically an exposed jockstrap pant for men. He told Newsweek that “Clothing is an extension of the fig leaf — it put our sex inside our bodies. My pants put sex back where it should be.” They failed to take off, and Cleaver became a born-again Christian.

By 1975, life in exile had lost its appeal. Cleaver surrendered to the FBI and renounced his radical past. Back in America he pled guilty to the shooting and was given parole. He soon became disillusioned with the commercialization of Christianity by Evangelicals, and attempted to launch the Eldridge Cleaver Crusades, a hybrid of Islam and Christianity called “Christlam.” He eventually converted to Mormonism, and regularly lectured at LDS gatherings.

He also spoke at the California Republican State Central Committee meeting on his journey across the political spectrum, and ran for several offices. He lost the Republican Party primary for the Senate seat in 1986, and when he insisted the Berkeley City Council begin its meetings with the Pledge of Allegiance, Mayor Gus Newport told him to “Shut up or we’ll have you removed.” He was arrested for burglary in 1988, and was sent to a drug rehabilitation center. He was arrested two more times for possession of crack cocaine, and, ten years later, died in Pomona Valley Hospital Medical Center on May 1, 1998. The cause of death was not revealed.

Bobby Hutton and Eldridge Cleaver are buried at the Mountain View Cemetery in Altadena, California. DeFremery Park in West Oakland was unofficially named after Hutton, and a memorial event commemorating his life and dedication to black consciousness has been held annually since 1998.

Alexander Auctions is offering for sale a diary entry that Cleaver wrote in 1987, on the nineteenth anniversary of Hutton’s death, and around the time of his divorce from Kathleen. In his own handwriting on the page, Cleaver notes he will not be commemorating Hutton’s death at a Free Huey event at Uhuru House, an indication of his gradual adoption of more conservative values. Huey Newton by then had been free for 17 years; two years later, Newton would be shot to death in Oakland. The Uhuru House however is still open and serving the community.

Alexis Coe is now a writer living in San Francisco, but not long ago, she was a research curator at the New York Public Library. Her work has appeared in the Atlantic, Slate, The Millions, The Hairpin, and other publications. Alexis holds an MA in history. Follow her.