W. H. Auden's Juicy Missing Diary Appears! And Then Promptly Disappears, For $74,426.56

Hello, would you like to buy something weird? Hammer Time is our guide to things that are for sale at auction: fantastic, consequential and freakishly grotesque archival treasures that appear in public for just a brief moment, most likely never to be seen again.

Sixty-two years after its publication, notable events in New York City caused the poem “September 1, 1939” to be immediately, and repeatedly, invoked. Its application seemed clear. But so much of Wystan Hugh Auden’s poetry — for both his generation and those to follow — is full of the kind of abstraction that is less readily apparent, of verses that slowly unfurl with each reading.

The sentiments Auden shared in his journals, however, are far more direct. Today Christie’s auctioned off one of the most important, believed to be lost for decades, with a price tag of £47,475 ($74,426.56, at this afternoon’s exchange).1 That value means, unfortunately, that it’s unlikely that the journal has ended up in a public archive. (Christie’s London office didn’t respond to an email asking about the identity of the purchaser. Update, June 14th: That’s because the purchaser has lots to consider in going public. But terrific news! The diary has been purchased by The British Library. Good for them, good for all of us.)

The 96-page journal covers August 30, 1938 to November 26, 1939, offering an intimate look at a particularly important era in Auden’s life.

At 32 ½ I suppose I shall not change physically very much for some time except in weight which is now 154 lbs…I am happy, but in debt…I have no job. My visa is out of order. There may be war. But I have an epithalamion to write and cannot worry much.

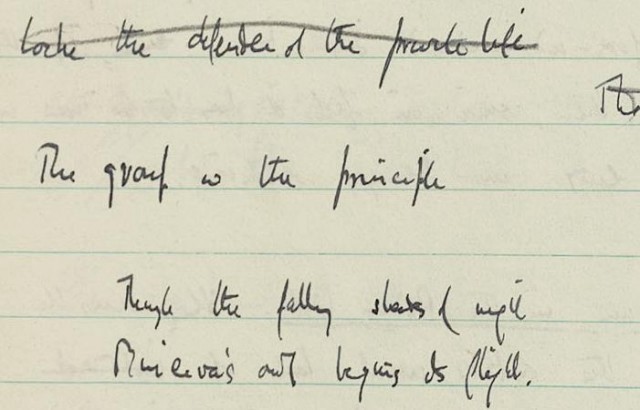

Auden turned to the journal in earnest as “a discipline for my laziness and lack of observation” in September of 1939, after spending “the eleven happiest weeks of my life” in California with the young hottie Chester Kallman, the poet and librettist who would become his lifelong companion.2 The pages consist of fragments written in pen, most lightly canceled out in pencil, with versos dedicated to idiosyncratic aphorisms, metrical experiments, reading notes and quotations. The last twenty leaves are purportedly filled with popular phrases and verse drafts, including sketches for eight or more sections of the long, philosophical poem, “New Year Letter.”3

Christie’s has released few spoilers, but we know it includes such admissions as “My hatred of women is such that if I am not afraid of them… I am cruel.”

Auden in 1931

He observes that “All the great heretics Pascal, Rousseau, Lawrence, Kafka etc have been sick men” and “It is impossible to listen to music and get an erection at the same time.” The importance of music — particularly by Wagner — is addressed throughout, as are works read, most notably by Gustave Flaubert and Laura Riding. He attempts John Milton’s 1642 An Apology for a Pamphlet, but fails because “The adjectives are wonderful but there are too many of them.” Auden, an Englishman who had just moved to New York, criticizes the practices of his adopted homeland, writing “Mean like the American habit of washing one’s hands after pissing, as if the penis were an object, too filthy for any decent person to touch.”4

Many of the famed residents of what Anaïs Nin later dubbed the “February House” — 7 Middagh Street, in Brooklyn Heights, rented by George Davis in 1940 — make an appearance. Davis, then the “literary” editor at Harper’s, seems to be a favorite lunch date, and was the man to whom Auden originally entrusted the journal.5

And Auden, like many of his soon-to-be roommates, really was good and broke:

Dear Harry,” Auden wrote to an editor at The New Yorker in a desperate note accompanying some poems, “PLEASE sell this to the New Yorker as I am VERY VERY VERY poor … I STILL HAVE NO HOT WATER. I STILL HAVE NO HOT WATER. I shall go crazy.”

The February House into which he would soon move was a wreck, though Auden brought some order to it, living on the top floor with Benjamin Britten, and also sometimes hosting his own wife, Thomas Mann’s daughter Erika, and her equally gay brother Klaus. (Auden and Mann had married in 1935, so that she could get a passport: “What else are buggers for?” Auden wrote. She was stripped of her German citizenship five days after their marriage.) Soon enough, anyway, the house would be bulldozed for the BQE.

Back in the diary, Gerald Heard, Archibald MacLeish, and Kallman, of course, frequently fill Auden’s days. So does drinking, smoking, and taking Benzedrine and Seconal.

But the entries written in the Fall, set against the outbreak of World War II, would be of greatest interest to scholars. Consider Auden’s notes below, which would contribute to “September 1, 1939”:

Sept 1st. Woke with a headache after a night of bad dreams in which C[hester] was unfaithful. Paper reports German attack on Poland… 6.0 pm. Benjamin [Britten] and Peter Piers [sic] came to lunch. Peter sang B’s new settings of Les Illuminations and some of H. Wolf…which made me cry. B played some of Tristan which seems particularly apposite today. Now I sit looking over the river. Such a beautiful evening and in an hour, they say, England will be at war…10:30 Went to the Dizzy Club. A whiff of the old sad life. I want. I want. Je ne m’occupe plus de cela. Stopped to listen to the news coming out of an expensive limousine.

One certainly hopes that the purchaser offers the public unfettered access, but if that day never comes, all is not lost. Christie’s notes that digital copies have been deposited with the Auden Estate and the Kurt Weill Foundation, though they are closed until April, 2014. So, it seems the plebe’s best bet is still the nearest library. See you next year!

Auden and Kallman, in Venice in 1951

1 Christie’s says that this journal is one of three he was known to have kept, and while it certainly speaks to an important time in his life, the claim seems dubious. The New York Public Library’s Berg Collection of English and American Literature has a substantial collection of Auden’s papers, and lists “diaries for 1959 through 1973, and journals for 1929 through 1964” on the finding aid. In a perfect world, it would end up at the NYPL, or another public archive with substantial Auden holdings.

2 They would be lovers for next two years, but Auden demanded monogamy, and Kallman could not abide. In 1941, he ended their sexual relationship, but they lived together from 1953 until Auden’s death in 1973. Kallman and Auden met when Kallman was 18.

3 Purportedly, because I did not see it with my own eyes. Christie’s has offered few glimpses at the journal.

4 Auden’s move to New York was considered quite a betrayal. It was even debated in Parliament. He left an Englishman, but in New York, Auden became the kind of European who wrote poems about Voltaire, co-owned a shack in Cherry Grove on Fire Island (shortly after the island’s devastation by the hurricane of 1938) and dressing up in camp costumes for parties. In 1946, he became an American.

5 It disappeared shortly after, only to be found recently. No more is known, or at least has not been made public, about the journal. It has been authenticated by Christie’s. They also consulted with the literary executor of the Estate of W.H. Auden, Columbia professor Edward Mendelson.

Alexis Coe is now a writer living in San Francisco, but not long ago, she was a research curator at the New York Public Library. Her work has appeared in the Atlantic, Slate, The Millions, The Hairpin, and other publications. Alexis holds an MA in history. Follow her.