The Nobel Peace Prize For Espionage

Hello, would you like to buy something weird? Hammer Time is our guide to things that are for sale at auction: fantastic, consequential and freakishly grotesque archival treasures that appear in public for just a brief moment, most likely never to be seen again.

On February 28, 1933, the Reichstag Fire Decree gave Adolf Hitler the emergency powers he needed to suspend civil liberties, and the Nazi party wasted no time targeting political opponents.1

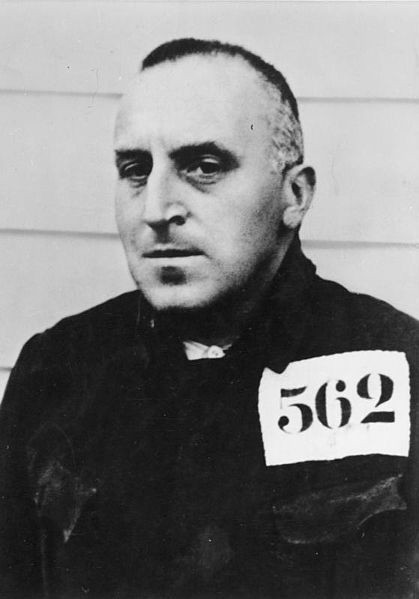

Carl von Ossietzky was arrested by the special police that very morning. It was not the first time the editor-in-chief of Die Weltbühne (The World Stage), the voice of leftist intellectuals, had been in a German prison. After Ossietzky ran an article exposing Germany’s secret rearmament, a clear violation of Treaty of Versailles, he was convicted of “treason and espionage.” He was sentenced to 18 months in Spandau Prison, but was released after seven months for the Christmas amnesty.2

The first time Ossietzky entered a Berlin prison, he was led by a procession of prominent German intellectuals, but many of those dissidents fled when Hitler was appointed chancellor in January of 1933. Philosopher Walter Benjamin lit out for Paris, and scientist Albert Einstein left to visit America and never returned, calling the Nazi takeover a “psychic illness of the masses.”

Ossietzky refused to leave his country, reportedly saying “a man speaks with a hollow voice from across the border.”3 He was an avowed pacifist dedicated to the restoration of “the other Germany,” the one he watched collapse as a soldier during World War I. Reactionaries on the right were actively seeking to amplify Germany’s power and militarism through fascism, and Ossietzky was determined to challenge them at every step.

This time, however, the Berlin prison did not release Ossietzky to freedom. Hitler hurriedly established concentration camps to imprison nearly 45,000 political opponents. Ossietzky was first sent to the Sonnenburg concentration camp shortly after it opened, and later Esterwegen.

In the camps, Ossietzky was subjected to hard labor and tortured, deprived of medical attention, forced to live in unsanitary conditions, and deprived of adequate sustenance. According to fellow prisoners, he suffered a heart attack, but the forced labor continued.4

By October of 1934, a small but notable group of European intellectuals began calling themselves the Freundeskreis Carl von Ossietzky. They launched a letter-writing campaign on the pacifist’s behalf. William Butler Yeats declined to get involved, asserting “he never meddled in political matters,” especially those outside of Ireland. But Virginia Woolf, Aldous Huxley, and Rose Macaulay readily showed their support.

Few believed Ossietzky would be freed. The Freundeskreis hoped that the editor’s plight would force the world to acknowledge the atrocities in Nazi Germany. The Third Reich was just a year old, and many still believed, or chose to believe, that Hitler could be reasonable.

When the letters received little response, the campaign took on a more specific goal: The Nobel Peace Prize. Romain Rolland sent a letter of support to Oslo, asserting the committee “has never before had the opportunity to crown an apostle of peace who had remained true to his cause until martyrdom.” But as a recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, Rolland could not nominate Ossietzky.

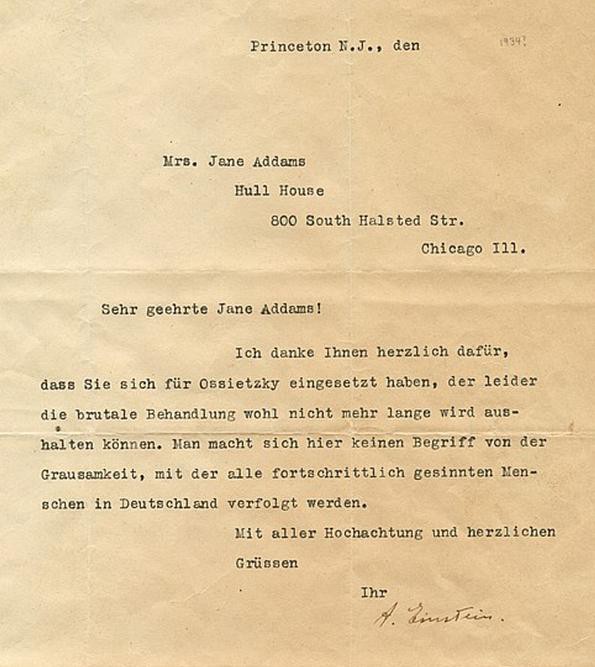

Albert Einstein, who had won the Nobel Prize for Physics, wrote to the committee as well. He was teaching at Princeton, and focused his efforts on American recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize, hoping he could convince them to nominate Ossietzky. Among others, he wrote to Jane Addams, the first American woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize.5 The founder of Hull House was a well-known pacifist, and immediately cabled a nomination to Oslo.

On July 10th, Profiles in History will auction off a letter of appreciation written by Einstein, with a starting bid of $6000.

Dear Mrs. Jane Addams!

Thank you so much for supporting Ossietzky, who unfortunately won’t be able to endure the brutal treatment much longer. People here cannot imagine the cruelty suffered by all progressive people who are being persecuted in Germany.

Yours respectfully,

Einstein

In addition to laureates, the group also lobbied Norwegian politicians and other nominees shortlisted for the prize. Czech President Tomáš Masaryk, considered the frontrunner, was convinced to show support for Ossietzky, but no committee member dared to push the nomination through.

In 1935, there was no Noble Peace Prize awarded. The committee, afraid to offend the new regime, announced they would exercise their right to reserve the prize for the following year.

After the announcement, Norwegian Nobel Laureate Knut Hamsun published a pro-German attack on Ossietzky. The essay incensed other writers, liberals, labor groups, and students, who actively took up Ossietzky’s cause. Back in Paris, Freundeskreis sought to capitalize on the controversy. They made Ossietzky’s writings on peace widely accessible to Nobel laureates, along with a memorandum arguing that he deserved the prize for peace, and it was not an attempt to free him. In response, Oslo received a record-breaking number of nominations from 86 laureates in 11 countries.

With the 1936 Berlin Olympics rapidly approaching, the Nazi regime’s effective propaganda campaign was being hijacked by Ossietzky. His imprisonment was not only a distraction, but it brought attention to concentration camps. When the Red Cross insisted they be allowed to visit Ossietzky, Hitler felt obligated to agree.

Swiss diplomat Carl Burckhardt was sent to visit Ossietzky, who he found gravely ill with tuberculosis. In his report, Burckhardt described him as “a trembling deadly pale something, a creature that appeared to be without feeling, an eye swollen, teeth apparently smashed, it dragged a broken, badly healed leg… a human being that had reached the uttermost limits of what can be borne.”

The German government feared that Ossietzky would die, and made a great show of sending Ossietzky to a prison hospital. Following the lead of the Freundeskreis, the Nazis pressured Nobel laureates to write to the committee as well — in support of Baron Pierre de Coubertin of France, who founded the modern Olympics. They also challenged the assertion that Ossietzky had ever been advocate of peace, disseminating anti-Ossietzky materials at home and abroad, including a fabricated interview in which Ossietzky proclaims, “Heil Hitler!”

The advisor who drafted the original report on Ossietzky assured the committee the documents were falsified, but many of the members took Germany’s threats seriously. Halvdan Koht, the Norwegian Foreign Minister who sat on the committee, withdrew from deliberations. The Prime Minister, Johan L. Mowinckel, left shortly after.

In 1936, the committee nonetheless announced Ossietzky was indeed awarded the previous year’s Nobel Peace Prize. In his speech, committee chairman Fredrik Stang made it clear they were not disapproving of the Nazi regime, and made no mention of the concentration camps, concluding: “In awarding this year’s Nobel Peace Prize to Carl von Ossietzky we are therefore recognizing his valuable contribution to the cause of peace — nothing more, and certainly nothing less.”

Nazi Germany, however, read the award as a direct critique. The Reich formally complained to the Norwegian government, and Hitler sent Hermann Wilhelm Göring to deal with Ossietzky in the prison hospital.6 The Gestapo, which Göring founded in 1933, argued that even if they accompanied Ossietzky to Oslo, he might escape, and would most definitely use the prize money to speak out against Germany. Instead, Göring offered Ossietzky a deal. If he rejected the prize, the German government would offer him freedom and a pension. Ossietzky proved more determined than ever, declaring, “I was a pacifist, I remain a pacifist.”

The German Propaganda Ministry publicly declared that Ossietzky was free to accept the award, but denied him the passport to do so. The Nobel committee sent the prize money to Germany, which was promptly stolen by Ossietzky’s lawyer.7 The German press was forbidden to comment on the prize, while the government proclaimed that all future German nominees were obligated to reject it.8

Ossietzky was moved to a private sanitarium, where he clung to life for another 17 months. The Gestapo guarded his room, regulating correspondence and visits.

On May 4, 1938, Ossietzky died from tuberculosis and other injuries resulting from three years in concentration camps. That same year, Time named Hitler “Man of The Year.”

In 1990, Rosalinde von Ossietzky-Palm called for her father’s high treason and espionage conviction to be reopened. Two years later, Germany’s Federal Court of Justice upheld the 1931 ruling, stating:

According to the case law of the Reichsgericht, the illegality of covertly conducted actions did not cancel out the principle of secrecy. According to the opinion of the Reichsgericht, every citizen owes his Fatherland a duty of allegiance regarding information, and endeavors towards the enforcement of existing laws may be implemented only through the utilization of responsible domestic state organs, and never by appealing to foreign governments.

While that ruling was unfortunate, just last week Julian Assange said that the new “mark of international distinction and service to humanity” was not the Nobel Peace Prize, but rather an indictment for espionage. 9

1. The February 27, 1933 arson attack on the Reichstag building, which housed the German Parliament, enabled the Nazis to become the majority party. Hitler had become the Chancellor of Germany just four weeks before the fire, but the mass arrests of Communists and other political opponents allowed him to greatly consolidate his power.

2. He had been the editor of the article, but the writer was Walter Kreiser. He was convicted and sentenced to 18 months in prison as well, but fled Germany. While Ossietzky did not appear to show any particular attachment to Christmas, his parents were Catholic and Protestant.

3. Biographer Wilhelm von Sternberg has speculated that Ossietzky, given a few more days, would have fled as well. Given Ossietzky’s contention that his voice would lose potency outside of Germany, compounded with a later offer of freedom that he rejected, suggests that the Sternberg’s suggestion was a highly debatable opinion.

4. In 1934, Heinrich Himmler’s SS took over the concentration camps and began purging Germany of “racially undesirable elements,” including Jews, criminals, gay men and women, and Gypsies.

5. Addams had won the prize in 1931 for her “expression of an essentially American democracy,” and donated the money to the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. She was regarded as the most prominent woman reformer of the Progressive Era, helping bring attention to women’s issues.

6. Hitler would name Göring as his successor in 1941.

7. The German government sentenced the lawyer to two years of hard labor for embezzlement, and forced the gravely ill Ossietzky to attend the show trial. It would be his last public appearance.

8. The proclamation would prevent three German citizens from accepting their awards: Richard Kuhn and Adolf Butendant won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1938 and 1939, and Gerhard Domagk won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1939. The committee would eventually reissue their certificates and medals, but not the prize money.

9. Assange, who is wanted for espionage, wrote, “It is getting to the point where the mark of international distinction and service to humanity is no longer the Nobel Peace Prize, but an espionage indictment from the U.S. Department of Justice.” He was referring to Edward Snowden, who is the eighth person to be charged with espionage under President Barack Obama. Widney Brown, Senior Director of Amnesty International, worries that Snowden’s “forced transfer to the USA would put him at great risk of human rights violations and must be challenged.”

Alexis Coe is now a writer living in San Francisco, but not long ago, she was a research curator at the New York Public Library. Her work has appeared in the Atlantic, Slate, The Millions, The Hairpin, and other publications. Alexis holds an MA in history. Follow her.