Today You Can Buy Queen Mary I's Secret Trump Card

At the age of 15, King Edward VI was dying. For his last act as king, he excluded both of his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth, from the line of succession. (To get Mary out of the line, he had to ditch them both.) His Protestant cousin, Lady Jane Grey, was named the Queen of England.

Two days after his death, Mary raised an army of nearly twenty thousand. It took just nine days for Mary — the only child born to Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon — to correct her half-brother’s final request. Coercion by force was an effective instrument, and it would come to define her reign.

At 37, Mary finally got that throne, and she intended to stay to there.

The Queen was indeed her father’s daughter, but she would avenge her mother’s unceremonious banishment, and restore the kingdom to the sovereign nation she was born into: England would once again be Catholic, Spain would be an ally, and threats to monarchy would be quelled immediately.

Marriage was the solution to every problem she had. It would produce an heir, ensuring that Elizabeth, her Protestant half-sister, would be once again removed from the immediate line of succession. Of course, that would come with a bit of satisfaction: Elizabeth was born to Anne Boleyn, not only the progenitor of Henry VIII and Catherine’s divorce, but also of England’s break with Rome.

The House of Commons formally requested Mary take an English husband, with an eye towards Edward Courtenay. Whereas they saw a handsome nobleman, Mary saw a poor politician.

Edward Courtenay

Philip II, the heir apparent of Spain, was much more to her liking. He was born on the same soil as her mother, and both descended from Isabella and Ferdinand. By marrying Philip, she could repair relations with Spain, and once again be allied with the Catholic country.

Philip II of Spain

She announced her intentions. The news was not well received. In court, the marriage was called unpatriotic. Mary responded gamely, agreeing to a Marriage Treaty. Philip could not hold office, and would cease his affairs in England upon her death, and, meanwhile, give her the lion’s share of authority to rule.

In Kent, Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger was not so easily pacified. He swore the marriage would turn England into “a cockleboat towed by a Spanish galleon,” but in the 16th century, political and religious concerns were not mutually exclusive. Wyatt was Protestant, as were the powerful men he sought out.

Sir Peter Carew, a member of Parliament in Devon, could be counted on to dissent, although he was reckless. Fear-mongering about the arrival of Philip, he said that the Spanish Inquisition, a reign of terror in the name of Catholic Orthodoxy, was surely on its way to England’s shores. Henry Grey, 1st Duke of Suffolk, and Sir James Croft, of the influential Herefordshire family, soon joined up. Recognizing an advantageous power play, the French Ambassador promised a fleet of ships to block the ships that Philip would surely send.

They planned to march on London in three months’ time. They wanted Elizabeth to ready herself for the throne, and wrote as much in a letter that was intercepted. A warrant was issued for Carew’s arrest, but he fled, only to be captured in Normandy. Croft panicked. Grey, the most determined of the group, scarcely managed to inspire 140 rebels to join him, most of whom he was paying. He soon gave himself up as well; the French ships abandoned the cause completely.

Wyatt was undeterred, and resolved to set out for London in January. By the 26th, his troops occupied Rochester, and the populace seemed eager to hear his scheme. They too distrusted Philip, but their dissatisfaction had been allowed to fester long before the Queen was coronated. Kent, far more than other parts of the country, had been most affected by the reformers. 4,000 men readily pledged their allegiance to the rebellion.

So then Wyatt’s rebellion had the Queen’s full attention. She allowed a delegation to seek out his terms, and summoned Elizabeth to court. Her half-sister came willingly and denied involvement, but that did not save her from the tower that once held her mother. It was a precautionary measure, Elizabeth was told, but as interrogations wore on, it was clear her head was at stake.

“Sir Thomas Wyatt the Younger,” Hans Holbein the Younger

The delegation returned with rebel demands: Wyatt wanted the Queen placed under his charge. Mary embraced the moment as political theater, riding to Guildhall to make the details public. She read his demands as outlandish, and defended her position as Queen. The audience, once sympathetic to outcry over the marriage, now rallied around Mary, accusing the rebels of heresy and sedition. The Council even came to her bedchamber at four in the morning on February 7th, worried about her safety.

While Mary appreciated the support, she had it on good authority that Wyatt was forced to abandon his artillery in the muddy riverbanks at Kingston. Besides, her course of action had been decided long ago.

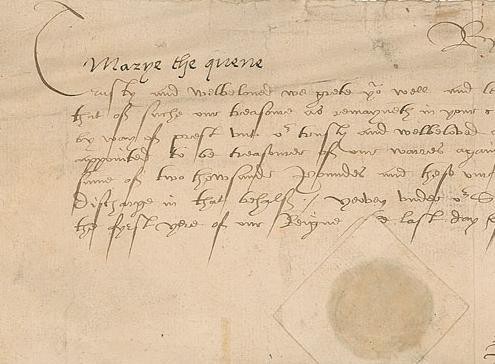

Just six days after the rebellion began, “Bloody Mary” had signed its death sentence. The document above — which is up for auction — may be written in Old English, but Mary’s intentions are as clear as her signature. She authorized the “treasourer of our warres against our rebels of o[u]r countie of Kent the sume of two thousand poundes.” By the time rebels reached the London Bridge, the treasurer had spent the money on a substantial force to confront them. Wyatt attempted another route, but when his army saw that security measures had been implemented, the majority fled or surrendered.

Wyatt was surrounded. He surrendered, but unlike the other ninety rebels who were either pardoned or hanged, Wyatt was tortured with purpose.

Mary hoped that physical pain and mental anguish would compel him to implicate Elizabeth, but he refused to name her as a conspirator. He was beheaded, the punishment for the charge of high treason. His corpse was then quartered, and his limbs circulated around the city, along with his head. Most of his extremities, and most certainly his head, were eventually stolen, as were his family’s land and titles.

The treasury document above, signed “Marye the quene,” is up for auction today. To compete in the final auction, bids are due by 6 p.m. After 26 bids, the current price is at $20,963.

Queen Mary I

Alexis Coe is a writer living in San Francisco, but not long ago, she was a research curator at the New York Public Library. Her work has appeared in the Atlantic, Slate, The Millions, and other publications. Alexis holds an MA in history. Follow her.