How Writers Can Get Paid Now: Adventures In Invoicing Your Copyright Violators

by Abe Sauer

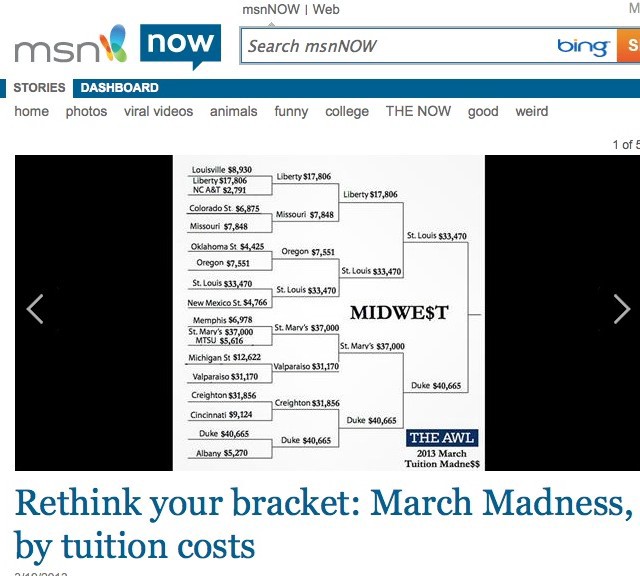

In March, I put together the fourth annual March Madne$$: The School Tuitions Of The NCAA Bracket. A popular piece, I watched as numerous sites reposted the work wholesale and sold ads against it.

That’s when I tried something new in the ongoing efforts of writers to get paid on the Internet. Instead of angry emails or cease and desist notes, I just sent invoices to site editors and managers.

To my surprise, one paid me.

Writers of original reporting or editorial work — journalists and others — are accustomed to the brave new race to the bottom of content aggregation, or, in more friendly terms, a system by which an original story’s “atomic units” are used “ to reinvent the news-consumption experience.”

Do legwork (or phone-work), get interviews, break a story, create art or charts, uncover information that was theretofore uncovered — and then sit back and watch as the guts of those pieces are aggregated with some “value-add” garbage (“curatorial”), making visiting the original piece unnecessary and unprofitable which, ironically, makes the publication that paid for the piece less inclined to pay a writer for future original content that can just be aggregated.

After The Awl posted the March Madness piece, I watched as blogs and other sites republished it. This case was especially aggravating since the brackets had been made as flat images with “The Awl” watermarks specifically to discourage such reposting.

It’s true that the tuition brackets idea itself is not protected. I did the brackets in 2009, 2010 and 2012, but by no means do I own the concept. Founder and Executive Director of Scholarship Junkies, Samson Lim, took the time to do the brackets by average net price, or “what you pay after grants and scholarships are subtracted from the college or university’s cost of attendance.” (It’s not The Awl winner Bucknell, by the way.)

Meanwhile, website eCollegeFinder.com posted its own brackets for tuition — with the same Bucknell result — a few days after The Awl. The site also ran other brackets by professor-to-pupil percentage and “built-in fan base.” And, ten days after The Awl’s post, The Hartford Business Journal posted its own version, sponsored by Tomorrow’s Scholar® 529 Plan. In these cases — and especially the identical eCollegeFinder one — the information was organized in new brackets with the site’s own marks.

Some of the publications that had reposted The Awl work were money-making endeavors. In a few cases, the blogs were under the umbrella of massive media companies, the kind that go on public crusades over how copyright infringement is damaging their business.

So I selected a number of offenders, created publication-specific invoices for each, and sent those invoices to the publication editors and managers with a note of thanks for buying my piece.

To get it out of the way, only one publication responded and paid me.

One typical reaction to the invoice was an apology and a removal of the post. This was the case for Washington, D.C.-based blog In The Capital, which had published The Awl work in a slideshow on its site.

Next Impulse Sports (formerly “Cosby Sweaters”) — one of Time Magazines Best Websites of 2012! — was brazen enough to not only post the full brackets but also the lead paragraph. The site is owned by Next Impulse Media, motto: “We create

digital content for grown men” (emphasis, mine). Next Impulse Sports did not respond to the invoice. The post remains up.

But some of the sites were bigger.

* * *

Seattle’s KMPS 94.1 went out of its way to reassemble the five-part tuition bracket to fit its page. Lest KMPS be mistaken for some artisanal ham radio operator, it’s a station run by CBS Radio Inc.

Meanwhile, KISS 106.7 (“All the hits for Rochester”) also posted The Awl brackets. KISS is part of the Clear Channel Media and Entertainment network.

Clear Channel’s own copyright and trademark policy states that “The Clear Channel Site, and all of its contents, including but not limited to articles, other text, photographs, images, illustrations, graphics, video material, audio material, including musical compositions and sound recordings, software, Clear Channel logos, titles, characters, names, graphics and button icons (collectively ‘Intellectual Property’), are protected by copyright, trademark and other laws of the United States.”

In essence, by putting all of The Awl’s work on its site, Clear Channel is claiming the work now falls under its copyright. Or did a $16.3 billion American mass media conglomerate just blow your mind?

The CBS digital media policy governing the KMPS site is equally absurd in this case. It reads, in part: “The content, information, data, designs, code, and materials associated with the Services (‘Content’) are protected by intellectual property and other laws. You must comply with all such laws and applicable copyright, trademark, or other legal notices or restrictions.”

Delicious too that Clear Channel’s parent company, CC Media Holdings, was a big financial backer of politicians intent on passing the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) bill.

As with Clear Channel, CBS’ claim that “we reserve all other rights to the Services and Content” seems to claim copyright over my work simply because CBS used it.

CBS has been very litigious when it comes to what it sees as its intellectual property. In January, the network sued Dish Network over the satellite provider’s ad-skipping technology. CBS, in just one more juicy bit of irony, argues that ad-skipping threatens to devalue its platform by robbing CBS of ad revenue. CBS even had CBS Interactive’s tech media service CNET boot Dish from contention for CNET’s “Best of CES” list.

Neither CBS’ nor Clear Channel’s stations replied to several invoices. The posts remain on their respective sites months later, just to the left of the advertising.

* * *

So, who paid?

Microsoft has — rightly so in many cases — been complaining about intellectual property piracy for years. In fact, Microsoft is daily engaged with a war on piracy. It recently sued Australian radio stations regarding software. It squeezed a per-unit licensing fee out of Nikon after it discovered the Japanese camera maker was using its IP. The Washington-based tech company claims that China has a $9 billion software piracy industry, while its legal market is only $3 billion.

This sensitivity to the piracy issue may be why MSN was the only publication to respond positively to the invoice.

A day after The Awl post, MSN Now posted a slideshow of the original sides with a short note concluding “Go to slide 5 to see who wins.”

While MSN was slow to respond and the invoicing took a few sendings, I was finally contacted by a legal representative who saw to it things were crossed and dotted and signed. The final part of that agreement prevents me from disclosing the invoiced amount. But the agreement does make MSN the only site beyond The Awl that bothered — even if out of embarrassment — to put its money where its legal department is.

In light of other publications’ complete unwillingness to account, MSN rightfully comes out looking decent.

Was it worth the trouble to make the invoices and send the follow-ups? Probably not by itself. Is this approach likely to answer the question about how (and how much) writers can and should get paid? No, no it is not. But, as writers old and young and at every level of experience who struggle with the new realities of content ownership probably know, every little atomic unit of a dollar helps.

Abe Sauer is the author of How to be: NORTH DAKOTA. He is currently working on a book about Chinese consumers.

A note from the editors: The Awl’s publication agreements with writers explain that authors retain their copyright, and that we are merely purchasing a license to publish it. Most publications have writers cede copyright to the publication. Because of this, Abe was free to pursue his collection activities on his own behalf.