William Gibson On Burroughs, Sterling, Dick, Libraries, The Uncanny, The Web

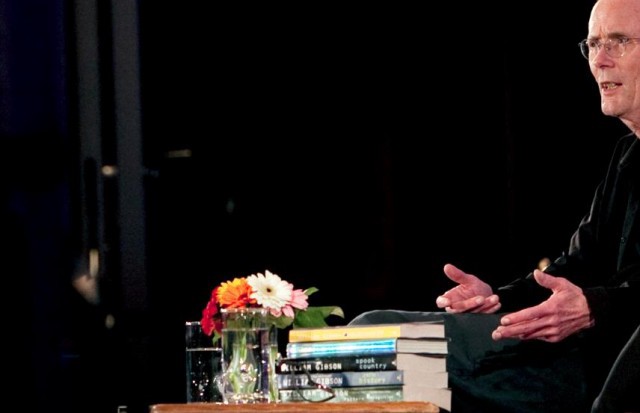

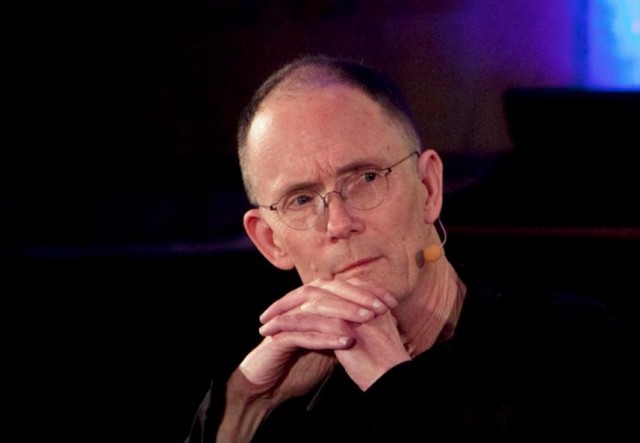

In real life, William Gibson looks like you would imagine. A little older than the Gibson you imagine, but he was born in 1948, so it only stands to reason. He is gaunt and affable, clothes black, smart looking frames on his eyeglasses, more avuncular than professorial. And he really talks like that! Those neologisms and the sizzling chrome-finished turns of phrase? They fall out of his mouth in the course of conversation. He lives the gimmick.

Gibson appeared at the New York Public Library on Friday night for the LIVE From the NYPL series, and it was something of an occasion. Gibson, as active as he is in social media, is somewhat known for begging out of extraneous obligations while he is in the process of writing a novel, which he is now. He did not explain why he broke his self-imposed solitude, but he did make some news, as he read publicly for the first time pages from his upcoming novel.

Gibson has described the upcoming book in a Tweet: “New novel’s an sf turducken: it’s got sf *inside* its sf, and arguably a loosey-goosey science-fantasy core.” At the event, he went one step further: he gave it a working title, The Peripheral, and he shared details of the structure. It is currently two storylines in alternating chapters, with two different narrators, with the first set in a recognizable future some thirty years from now, and the second in the way way way future (“It’s really hard to write,” he said). And then he went one step further and read from his iBook the first couple hundred words. It’s Gibson’s return to “ess eff,” as he referred to it a couple times, and if the first excerpt is any indication, it is good.

A transcript and video of the event will be posted by the NYPL in a week or two, at which time you may relive the event in real time, but in the meantime there were a few portions of the conversation that were funny and charming and absolutely worth sharing.

First off, the host and curator of the series, Paul Holdengräber, asked Gibson to talk about the influence that William Burroughs had on a young Gibson.

Gibson: I was probably twelve or thirteen years old, and I went virtually every day to the three rotating wire paperback book racks in the small rural town in Virginia where I lived, to see if there were any new books. The library burnt to the ground forty years earlier, and had never been replaced, so that was my library. Even though I knew that the books on the racks were only changed once a month, I’d still go every day just in case something new had arrived. And I literally checked out everything. And I found a very cheaply assembled anthology of Beat writing, which I bought and took home and hid from my mother, because I could see from the content that she wouldn’t approve of it. So I started reading the Beats out of this rather badly assembled little anthology. And I really couldn’t make head nor tail out of most of it. But then I hit their excerpts from Naked Lunch, which made no sense to me at all. Like reading messages from Mars. But I could sense that it was in part built out of science fiction.

Holdengräber: Really.

Gibson: In some cases quite literally, because Burroughs would chop up whatever ess eff he happened across and collage it into the text. So I could see the gristle of ess eff floating on this bilious soup of rectal mucus. And there I was at thirteen going, “Whoa, what is this, what is this about?” But even then I could sense that he was able to do something really remarkable with words, and that was what kept me reading Burroughs, was the extraordinary things he could do with the English language that I never encountered anywhere else. It was like discovering the one human being on Earth who could play slide guitar. So, that’s what I came back for. I didn’t come back for the baldly libertarian politics, or the super-cranky Reichian Dianetic stuff. I mean, I didn’t come back to Burroughs for the intellectual content, I came the extraordinary style, this completely original way of handling language. Because in some way, I wanted to play slide guitar. I wanted to figure out how he was doing it.

Holdengräber: You came back perhaps for the feeling of uncanniness.

Gibson: Yes. And by the time I encountered Burroughs, I had read a great deal of English language science fiction.

Holdengräber: What in particular?

Gibson: Mm, I read the central shaft of commercial ess eff, so, Heinlein, Bradbury. So I starred with that. But I very quickly found myself over in a sort of left-wing, reading Philip K. Dick and Robert Sheckley, people Heinlein probably would have found as being of a certain ilk. Definitely not West Point material. And all of these writers prided themselves on being able to hit the Uncanny Valley pedal now and again. Like you go, “Uhooooh, that’s weird!” I was reading these really mild publishable excerpts from Naked Lunch that were just blowing that stuff away. Burroughs’ foot on the Uncanny Valley pedal was an eye-opener.

As you can see, William Gibson talks just like his prose. It’s fascinating.

Speaking of which, Gibson has the most fabulous speaking voice, and he’s just riveting to watch speak. For a man who left the country in the late 60s and has never lived here since, he has a pronounced Southern accent. Not quite a drawl, but one of those DelMarVa accents that smoothes out some vowels thoughtfully. And it’s not a strong voice either, but one you pay attention to. He came off as politely attentive at first, and maybe a bit cagey once or twice, but once he got some downhill momentum as in the above exchange he gets this smile, almost at the wonder of it all.

Naturally, given the free-ranging nature of the conversation (which still felt abbreviated — an hour and forty minutes and no mention of the immediately previous trilogy?), the topic of the coining of the word cyberspace, arose, and Gibson gave the secret origin of the phrase:

Gibson: I came to that out of a perceived need to find an arena in which I could set science fiction stories. The science fiction arena of my childhood was space travel, and the vehicle was the rocket ship, the space ship. And in the late 70s early 80s, that wasn’t resonant to me. I knew I didn’t want to do that. I knew I didn’t want to to do the post-apocalyptic wasteland. I knew I wanted to try to write science fiction, but I didn’t have an arena. And I arrived at cyberspace —

Holdengräber: By arena, you mean?

Gibson: A territory, a place in which the story can unfold. And I wanted that sense of another realm, and I wanted a sense of agency for the characters, and particularly for the protagonist. She drives her (hmmm) through (hmmm). But I didn’t know what she was driving, and I didn’t know what she was driving it through. So in some odd way I think I began to mull over that and keep my eyes open while walking around in my daily life. Bits and pieces of reality, bits and pieces of something that could be cobbled into the arena I need this character to have, some sort of agency. And the pieces I came up with were just the sight of kids playing very early huge plywood-sided arcade games, and the body language of just intense longing and concentration and when I glanced into these arcades that I was probably afraid to go into myself, it seemed to me that like they wanted to go right through the glass, they wanted to be right there with the Pong, or whatever. But you could see that they wanted it, and I think I could also see that they were very likely to get more complicated games than Pong pretty quick. Which indeed they did. I had that, I had the big bus stop posters of the actual computer part of the Apple IIc, which was smaller than most briefcases. It was a very crisp-suited businessman arm, holding this thing, and it didn’t show you that there was this big clunky monitor that you had to have. He was just holding this thing with a keyboard on it. I knew people who were starting to buy Sinclairs and kits, building kits, like these incredibly primitive little computers that, you built it, and you had to keystroke all of the programs into it, and if you made a single mistake, the whole thing wouldn’t work. But I knew that people did that. I started hearing about people that connected home computers distantly via telephone, and because, fortunately, I knew absolutely nothing about computers, I was able to smoosh that all together and get this vague vision of my arena, which I then need a really hot name for. Dataspace didn’t work, and infospace didn’t work. Cyberspace. It sounded like it meant something, or it might mean something, but as I stared at it in red Sharpie on a yellow legal pad, my whole delight was that I knew that it meant absolutely nothing.

And I feel like no long conversation with William Gibson is complete without a cameo from Bruce Sterling. This is Gibson answering the question of whether he is in some way being transmogrified by his use of technology.

I don’t know, and I don’t think we can know how technology affects us. As soon as it affects us we become that which has been affected… I wrote Neuromancer on a manual typewriter, and Count Zero and half of Mona Lisa Overdrive. I was a very late adopter, a very late adopter, of the Internet. I’m increasingly not that way. What I find though is that the solitude of the act of seriously writing fiction is such that it comes within the whole loopy shitstorm social media that most of now live in. It comes anyway, and you’re absolutely alone doing this strange, sometimes, sometimes seemingly very hard and other times wildly exhilarating thing and there’s nobody else there, even though you’re Tweeting with the other hand. Some people disagree, they block the little holes in the laptop. I don’t have that problem.

Bruce Sterling had a computer before anyone else I knew. He had a computer he used as a word processor and I remember him calling me up one day and saying that he had a small television set with MTV on top of his monitor. He’d built this incredible distraction machine. “It’s great. man, you should try it,” and I’m shuddering delicately.

Let me advocate the use of actually seeing your living literary heroes speak live and in person. It will color all of your readings, and rereadings, of their work. It could be argued that a certain anonymity of voice is a prerequisite of good fiction, maybe. Sure. But just the small process of going back to consult Gibson’s work to double-check this thing was a trap door I found it difficult to resist — ”OMG, you stress that word in the phrase. And, it’s supposed to come off laconic.” It was fascinating to watch that mind work in real time.