When Food Attacks: A Selective History of Literature's Most Alarming Feasts

by Matt Seidel

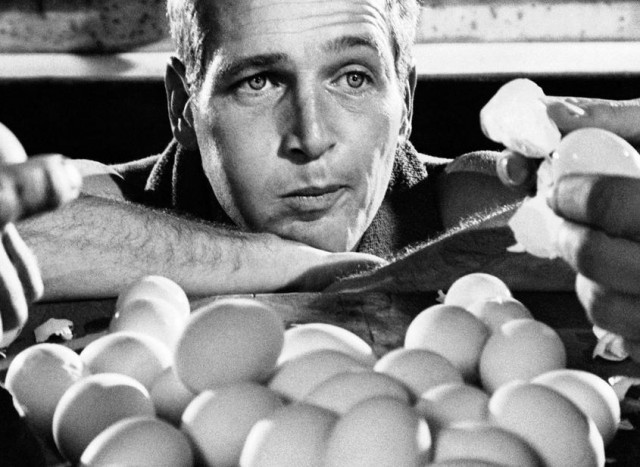

Paul Newman’s egg-gorging feat in Cool Hand Luke certainly inspires wonder (along with a tinge of disgust). And yet each time I watch the film, I struggle with a nagging question raised by that stomach-swelling exploit: Which came first, our appetite, or our drive for competitive eating? Owing to the glut of cooking competitions, food trucks racing across town serving up sliders and duck-fat tots, foodies one-upping each other on Instagram and restaurants aggressively advertising their farm-to-table bona fides (as brilliantly satirized on “Portlandia”), food culture feels increasingly competitive in the broader, non-Kobayashi sense.

As the battles unfold to perform more impressive culinary feats, whether inhaling hot dogs or crafting edible wonders using molecular gastronomy, we should pause to consider what happens when one combatant, the food, strikes back.

Though accounts of such rebellion are rarely recounted in real life, literature is a movable feast of culinary riches teeming with food both delectable — Mrs. Ramsay’s Boeuf en daube, Leopold Bloom’s tangy mutton kidneys, Proust’s madeleine, Prufrock’s uneaten peach — and devilish. This particular history deals with the feisty fare that refuses to go down one’s gullet without a fight. In this literary digest, a vicious sausage army attacks a giant, a barber finds something considerably worse than a hair in his food, spice leads to a diplomat’s ruin, a Roman gourmand stuffs himself too much to enjoy an historic belly-dance, a rich Elizabethan repast wages a brutal war against the intestines, a snobbish aesthete gets his hands on some poisonous mushrooms, and finally, a notorious bruiser meets his match in a steamed lobster.

1532

Over the course of François Rabelais’ five-part epic Gargantua and Pantagruel, food is a constant obsession, supporting the satirist’s contention that “Master Gaster — Sir Belly — is the true master of all the arts.” In one episode, Pantragruel and his travelling companions encounter King Lent, the abstemious dictator of Mustardland who “feared nothing but his own shadow and the bleating of fat kids.” As is often the case when Rabelais threatens to move the action forward, a tangent diverts the narrative down some fanciful path or intestinal byway. In this case, we receive a “monstrous anatomy” of the Lent, the tonsured “demi-giant,” of which here are some highlights:

His mammillary attachments like old shoes.

His spleen like a quail-decoy.

His spermatic vessels like puff-pastry cake.

His prostate gland like a feather-jar.

His bladder like a catapult.

If he frowned, it was pigs’ trotters fried in their own fat.

If he sweated, it was stock-fish in butter sauce.

If he blew his nose, it was salted eels.

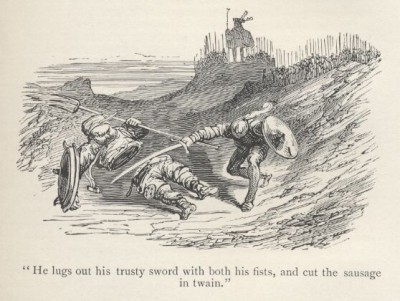

A Gustave Doré illustration for “Gargantua”, from 1854

King Lent has long been at war with a neighboring Savage Island, which is populated by wild Chitterlings and various other meaty comestibles (Blackpuddings, Mountain Bolognies). When Pantagruel arrives on the Chitterlings’ island, he and his men are marched on by 42,000 sausages “to the tune of bagpipes and flageolets.” Hostilities commence when “a stubby, wild saveloy” tries to seize one of Pantagruel’s companions by the throat. Luckily, Pantragruel has two aptly named commanders in his contingent, Colonel Maul-chitterling and Colonel Chop-sausage, as well as the indomitable Friar John, who herds his “cook army” into a wooden sow from which to launch a Homeric attack. The Chitterlings are saved from extermination only by the arrival of a giant flying pig flinging restorative mustard onto the battlefield. Any questions?

Detail from Pieter Bruegel’s “The Fight Between Carnival and Lent” (1559)

While Gargantua and Pantagruel revels in excess, it is also a perverse handbook for moderation, for how to wield one’s princely power, gigantic strength and outsized desires responsibly. And thus the allegorical battle between Lent and a sausage-packed Carnival seems particularly relevant in the giants’ struggles with their own appetites. Bruegel would later paint a more schematic version of this conflict, but Rabelais loses control of the allegory in the best way possible. He surrenders to a force greater than that of Lent or Carnival: his delirious and discursive imagination. More important than anything — the sex, booze, food and adventures — is seizing any opportunity to enlarge on his monstrously nonsensical anatomy of the world.

Everyone on the battlefield is controlled less by allegorical strictures than by language: “Maul-chitterling mauled Chitterlings; Chop-sausage chopped sausages”; and the cook army, composed of valiant men such as Cowardycustard, Gutspudding, Swillwine, Soused cod, Gnawbacon, Baconrasher, Snaildresser, Macaroon, Longtool, Oldtool and Hairytool, Muttonchop, Saffraneer, Chiefturnipeer, Tomturdy, Assface, and Rumblegut, is devised and called into action against the rampaging sausages. One is left with an ludicrous allegory and the only question in literature more baffling than “To be of not to be”: “The Swiss are now a brave and warlike people. But how do we know that they were not once sausages?”

1836

There is a Rabelaisian element of fanciful grotesquerie in some of Nikolai Gogol’s tales, especially “The Nose,” in which Major Kovalev’s nose disappears from his face one day and starts “driving around town calling himself a state councilor.” The story is an absurdist fable partly about snobbery, with Kovalev and his nose sharing an obsession with rank and title and knowing one’s place (literally and figuratively). It begins not with Kovalev but with his barber, specifically his traumatic breakfast: “…the barber Ivan Yakolevich woke up quite early and sensed the smell of hot bread.”

Gogol’s sly joke is revealed when the barber sits down to enjoy the treat:

Having cut the loaf in two, he looked into the middle and, to his surprise, saw something white. Ivan Yakolevich poked cautiously with his knife and felt with his finger. “Firm!” he said to himself. “What could it be?” He stuck in his fingers and pulled out — a nose!…and what’s more, it seemed like a familiar one.

Poster for the Metropolitan Opera’s premiere of William Kentridge’s production of Shostakovich’s adaptation of Nikolai Gogol’s “The Nose”

Ivan is awakened by his nose, only to find an actual nose in the food whose aroma stirred him from his sleep. There is just faint enough a trace of logic here to make the occurrence seem almost reasonable. As all great absurdist tales do, “The Nose” succeeds precisely by fitting an “extraordinarily strange incident” within an essentially realist house of fiction, which is why it is crucial that the nose is “familiar” to the barber. Similarly, when Kovalev finds his nose — reduced to its proper size, no longer strolling about town and sans uniform — he excitedly harps on a realistic detail: “That’s it!…There’s the pimple that popped out on the left side yesterday!”

Without explanation, the now pimple-free nose returns to its proper place on his face “on the seventh of April,” Kovalev not having learned any lesson “of benefit to the fatherland.” Though Kovalev’s vanity certainly invites moralizing, Gogol’s comedy is ultimately more concerned with exploiting the tension between realist forms and the “perfect nonsense [that] goes on in the world.” There are “incongruities everywhere,” perhaps even in your freshly baked, delicious-smelling bread.

1848

From the original cover of “The Book of Snobs”

Gogol’s vagabond nose ruins a Russian barber’s breakfast, but a Turkish delicacy in William Makepeace Thackeray’s The Book of Snobs ruins a Russian diplomat’s life. Thackeray’s diplomatic snob changes the course of history by smilingly eating a “horrible bolus” offered to him by his Turkish host, the Galeongee. In the episode, an English diplomat is trying to outmaneuver his Russian adversary, Diddloff, when each is offered the following dish: “Amongst the dishes a very large one…of a lamb dressed in its wool, stuffed with prunes, garlic, assafoetida, capsicums, and other condiments, the most abominable mixture that ever mortal smelt or tasted.”

The Englishman takes down the concoction with aplomb, but the Russian is not as skilled a statesman:

The Russian’s eyes rolled dreadfully as he received it: he swallowed it with a grimace that I thought must precede a convulsion, and seizing a bottle next him, which he thought was Sauterne, but which turned out to be French brandy, he drank off nearly a pint before he know his error. It finished him; he was carried away from the dining-room almost dead, and laid out to cool in a summer-house on the Bosphorus.

As a result, the British sign an advantageous treaty, and the Russian diplomat is last seen laboring in a Ural mine as “No. 3967.” Thackeray’s Vanity Fair may have been a novel without a hero, but The Book of Snobs supplies one willing to combat the vilest of delicacies for queen and country.

1877

Gustave Flaubert’s satire is subtler and more contemptuous than Thackeray’s, though the compiler of the Dictionary of Received Ideas surely would have appreciated the Englishman’s taxonomic study of snobs. In “Herodias,” his rendition of Herod’s feast from Three Tales, the target of Flaubert’s satire is a glutton, Aulus Vitellius, the decadent son of a Roman Proconsul who is better suited to Rome’s vomitoriums than Herod’s mountain citadel.

Tetrarch Herod Antipas has a lot on his plate even before John the Baptist’s head gorily appears on it. He must politically maneuver among Pharisees, Essenes, Arabs, Parthians, Sadducees, Jews and Romans; placate an aggrieved wife, Herodias; and silence a firebrand preacher, John the Baptist, critical of his ways. As that preacher wastes away in his dungeon, Aulus Vitellius stuffs himself to satiety, then vomits, then seeks a way to eat more: “Give me marble shavings, shale from Naxos, sea water, anything! What if I took a bath?”

Andrea Solari, “Salome with Head of St John Baptist” (1506)

Chewing on snow seems to bring back his appetite. Aulus feasts anew before the arrival of Herodias’ daughter, Salome, a postprandial treat if there ever was one: “Her movements were like sighs, and there was such languor in her body that it was not clear if she was mourning a god, or dying in his embrace.” The inflaming dance makes “the nomads accustomed to abstinence, the Roman soldiers experienced in debauchery, the avaricious tax gatherers, [and] the old priests made sour by endless disputes… quiver with lust.” Herod offers her half his kingdom and agrees to expedite John the Baptist’s execution. And Aulus? Perhaps made queasy by Salome’s gyrations, he vomits yet again. It is fortunate that Herodias didn’t invest all that time training her daughter to dance for him, since the libido is no match for such gluttony.

1929

Publicity image for the apparently terrible 1949 film adaptation of “Poet’s Pub”

The banquet in Eric Linklater’s Poet’s Pub is no less sumptuous than Herod’s but rather dull by comparison (what wouldn’t be?). In the novel, a young poet and former Oxford Blue rowing member, Keith Saturday, becomes the publican of an inn, The Pelican, in which Elizabeth I herself once stayed. To honor the anniversary of Elizabeth’s visit, Saturday, who once envisioned “writing a Gargantuan epic of food,” plans an extravagant Elizabethan meal for his eclectic group of guests. (We are told that in the Queen’s time, sixteen dishes was considered adequate for a good family feast.) Saturday’s verse pales in comparison to the menu, which is “a poem,” a “triumph of the imagination,” or as the chef malapropically puts it: “A node to the stomach.” The offerings — kickshawes, stewed pike, suckling pig, olive pie, roast capons, marrowbone — sound delicious, but consuming such a prodigious feast is not without consequences:

There was, in [Mr. van Buren’s] troubled belly, twenty-two feet of troubled gut and a tortured twisting canal six feet long. From his right arm-pit, it seemed, to his waist was a mountain of liver, a volcano in the throes of imminent eruption. Hostile fleets sailed upon his succus entericus, discharging their broadsides against his shrinking mesentery; and the appendices epiploicae, those tattered shreds of membrane, waved helpless in a flatulent gale like white flags of surrender that no one would see. He even thought of death; for he was past sixty, it was stark night, and his belly was a battlefield….

These eruptions, broadsides, and battles send the suffering guests in search of a loo, which affords the pub’s spies, thieves and snoops access to previously guarded rooms. In other words, for better or worse the meal gets both the digestive system and the plot moving. The Pelican’s journey back into the culinary past propels the novel forward, from a comedy of manners into a madcap chase to track down stolen documents, recipes and Saturday’s atrocious new manuscript.

As is always the case, comedy eventually digests and expels its conflicts, and in a touch that reveals Linklater’s charming wit, the theft of Saturday’s prized poetry actually puts him in higher stead with the pub’s owner, Lady Mercy Cotton: “Most poets were pleased enough if anybody borrowed their books, and here she had in her own service a poet who could get his own work stolen. It was a superb mishap.”

1996

The Elizabethan marrow pies and kickshawses cause Poet’s Pub’s feasters considerable discomfort, but worse fates befall the diners in John Lanchester’s The Debt to Pleasure. Tarquin Winot, a snob to rival Thackeray’s, is composing his “gastro-historico-psycho-autobiographico-philosophic lucubrations,” which, befitting the culinary theme of his narrative, is quite a mouthful. The “unconventional cookbook” is also a confession revealing the narrator’s gustatory predilections and unsavory acts. We receive Tarquin’s haughty, arch and learned digressions on all things culinary and aesthetic — the etymology of barbecue, the controversial nature of bouillabaisse, postmodern art, the edibility of puppy casseroles.

A young Amanita phalloides, photographed in Russia by Aleksey Gnilenkov

The entertainingly didactic narrator can’t resist informing the reader that he has not used “delicious” once in the course of his floridly written “memoir.” This is partly owing to Tarquin’s stylistic snobbery, but his aversion to “delicious” indicates a deeper philosophic stance. Tarquin cultivates an “erotics of dislike” vis-à-vis food, art and people: “The real meaning of our dislikes is that they define us by separating us from what is outside us; they separate the self from the world in a way that mere banal liking cannot do.”

While this “negative revelation” is certainly a welcome tonic to the pieties about food bringing people together or being cooked from the heart, The Debt to Pleasure is also a darkly comic novel about the isolating effects of good taste. Tarquin’s grandiose conception of himself as an artist becomes increasingly sinister as he employs his triumphant discrimination, and poisonous mushrooms, to separate himself from his fellow man: “So the agreeable taste of Amanita phalloides is a good joke on nature’s part, since the mushroom is very poisonous indeed — the most poisonous, in fact, in the world, and fully deserving of its common name, the Death Cap.” Woe to those not in on the joke — the only hope of a cure is ingesting raw minced rabbit brains — but Tarquin for one certainly finds the deadly fungi amusing. There’s no accounting for taste.

2012

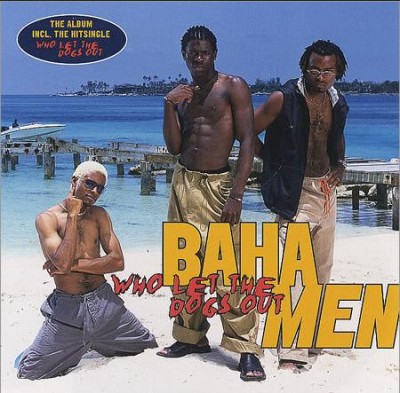

While we’re on the subject of taste, or lack thereof, there’s Martin Amis’ recent “State of England” novel, Lionel Asbo, which opens with a boy describing a torrid affair with his grandmother. The thuggish title character is notorious for being the youngest person ever to have received an ASBO, or Anti-Social Behavior Order. After winning the lottery, he finds himself flush with cash, out of prison, something of a celebrity and hungry. Amidst the novel’s incest, pornography, violence, humiliation, general depravity and bizarre fascination with the song “Who Let the Dogs Out,” one scene stands out from the satirical clutter: Lionel’s “climactic struggle with the main course” at an upscale restaurant.

Album cover for the Baha Men’s “Who Let The Dogs Out”

Swilling champagne from a beer mug and wolfing down caviar drenched in Tabasco sauce is merely the warm-up for his epic confrontation with a lobster, an “ugly-looking bugger.” Wary of “the monstrous hydraulics of the forearms,” Lionel proceeds cautiously at first in his determination “to confront the scarlet fortress of the crustacean,” which resists his advances by sending a “jet of hot butter” into his eyes. Never one to back down, the “Lotto Lout” attempts to breach the scarlet fortress with various utensils before deciding on a more elemental approach: “The key moment came ten minutes later, when he threw down his weapons and reached for the enemy with his bare hands.”

A perfectly placed ellipsis allows Lionel to carry on his struggle in peace and feels almost like an act of mercy on Amis’ part towards the paparazzo-hounded anti-hero. When we next see him, he is wounded, not mortally though needing stitches. Boiled alive though it may be, the lobster turns out to be the one creature in the novel capable of combating Lionel’s brutish bullying. Though Lionel takes the defeat stoically (“Next time, I’ll have the haddock”), he soon vents his pent-up rage by assaulting three uncarapaced photographers and landing himself back in prison, where at the very least he is free from the mocking glare, the “shrunken, horror-comic face” of his crustacean antagonist.

* * *

If there is in exquisitely prepared food the transcendent and poetic, there is also something depressingly earthbound and prosaic about having to stuff our gobs thrice daily. In The Pilgrim Hawk, a novella featuring a bird who experiences the most intense hunger in the animal kingdom, Glenway Wescott puts it more elegantly: “On the whole, throughout life as a whole, the appetites which do not arise until we have resolved to eat, which we cannot comprehend until we have eaten, are the noblest — marital, aesthetic, religious.”

There is a particularly human conflict between the elevation of our imaginations and the baseness of our needs, which is why it is so fitting that in Thomas Hardy’s Jude the Obscure, the lusty Arabella snaps the intellectualizing Jude out of his reverie by hitting him in the face with a bloody pig’s pizzle. Yet another victory for the underdog in the eternal struggle of man versus food.

Matt Seidel lives, writes and eats in Durham, NC. His stuff is up at Matthew Seidel Dot Com.