Whatever Happened to MTV's "Buzzkill"?

by Sean Manning

Not long ago, MTV made an unusual appeal: It asked for help finding information about one of its own shows. The show was “Buzzkill,” a hidden-camera program that ran in 1996. The plea came from MTV’s Guy Code blog:

If you try to find old clips online, they’re nonexistent. Seems impossible, right? The web is where you can find the most obscure remnants of every era, the most disturbing videos the human mind can conjure. And yet it has seemingly been scrubbed clean of all “Buzzkill” details…. Internet, we need your help. We must uncover the truth of “Buzzkill.” Send us your tips and clues. Better yet, if you have any old “Buzzkill” episodes on VHS, transfer that s*** to digital and send it our way.

I was already aware of this predicament. I was in high school when “Buzzkill” aired and I loved it. It was goofy — performing a seemingly fatal voodoo ritual, offering free shuttle bus rides to spring breakers then pretending to rob a convenience store with them in tow — but it was also smart. I didn’t get some of the gags and voice-over jokes, but that made me like the show even more. It wasn’t pandering. It didn’t just make me laugh, it made me think.

(Read later with Pocket.)

I had searched for “Buzzkill” clips a few times over the years without any luck. I figured the reason was simple: nobody liked the show enough. But with MTV’s imploring, I realized I was wrong. There were other “Buzzkill” fans out there. And I was suddenly very curious. Why didn’t the show last longer? What ever happened to the three guys in the cast? Were they themselves, as the blog speculated, somehow responsible for their Internet absence — was it one last grand prank?

Dave Sheridan

The summer before his senior year at William Paterson University in Wayne, New Jersey, Dave Sheridan had an internship in Manhattan with “CBS Evening News” host Dan Rather. A friend of his parents got him the job.

“I just needed a job,” Sheridan said. “I didn’t care about journalism. But every day Dan would call me into his office and offer me a cigar and say, ‘Son, let me tell you about being a reporter….’ I’d just sit there staring at his eyebrows.”

This was 1990, the summer the Gulf War started.

“CBS was doing these crazy graphics for their Desert Storm coverage. They had these jets flying over and this theme song and huge logo. They had a logo for a war! It was like ‘Monday Night Football.’ I just thought it was so over the top and ridiculous. I said, ‘I gotta meet whoever came up with that.’ It was this guy Steve in the graphics department. I went to see him and he was like, ‘Yeah, isn’t that hilarious?’”

Sheridan doesn’t remember Steve’s last name. “You could try and track him down. He was secretary of the Writers Guild East. Even if you did find him, I doubt he’d remember me.” (The Writers Guild East didn’t reply to an inquiry.)

“He asked me what I wanted to do with my life. I said, I want to be on ‘Saturday Night Live.’”

Sheridan had been doing comedy, he said, “since kindergarten.” In high school, he was also really into skateboarding. Hoping to get sponsored, he made home videos of himself skating. Eventually the skateboards disappeared from the videos, and he began filming skits of himself doing funny characters — including “Stewart,” the nunchuck-wielding, white-trash wild man he’d eventually reprise in the 2001 film Ghost World.

“I’ve got this friend Herb,” Steve told Sheridan. “Let me make a phone call.’”

“Herb” turned out to be Herb Sargent, who with Chevy Chase had created “Saturday Night Live”’s “Weekend Update” and was still its head writer.

“Steve made one call and got me an interview for an internship. I showed up and there were all these Harvard grads dressed in blue blazers and red-and-blue ties. I was wearing jeans and a tee shirt. That’s actually what got me the job. Herb said, ‘You look like a guy I can treat like shit and won’t quit. Will you quit?’ I said, ‘No,’ and he hired me.”

Sheridan interned at “SNL” for all of the 1991–92 season, the first featuring Kevin Nealon as “Weekend Update” host. He worked mainly as a gofer.

“This was pre-Internet,” he said. “So any photos they wanted to use for ‘Weekend Update,’ I’d have to run over to the Associated Press offices and get them.”

He also did some writing, even got a few jokes on the air. “They paid me $50 a joke,” he said.

Most significantly, Sheridan became friendly with cast members Adam Sandler, Chris Rock, and Chris Farley.

“They were still doing stand-up then, and they would take me with them and let me do five minutes before they went on. And I pretty much sucked. That’s exactly what they said. They’d come into the office and say, ‘You pretty much suck.’ Farley was finally like, ‘What’s your act, dude?’ I told him I did all these characters, and he recommended I go to Second City.”

The famed Chicago improv theater had produced some of the most legendary names in American comedy, including John Belushi, Bill Murray, and Farley himself.

Farley called Joyce Sloane — a longtime Second City producer and den mother who died in 2011 — and got Sheridan a job. He moved to Chicago in the summer of 1993. He didn’t receive a warm welcome.

“At Second City you start at the bottom,” he said. “Washing dishes, ripping tickets, sweeping the floor. They try to make you feel better. They’d be like, ‘David Mamet ran that same dishwashing machine,’ or ‘John Belushi was back here doing whippets.’ But there’s definitely a pecking order that needs to be respected. And here I am with Chris Farley vouching for me, and Joyce Sloan looking after me, and I’m walking around with a ‘Saturday Night Live’ employee jacket on. People were like, ‘Who the fuck is this guy?’”

Before long, though, he found two allies. Within three years, they’d be on national TV.

Frank Hudetz

Frank Hudetz’s mom was college friends with John Belushi and his younger brother, Jim.

“I always heard about John growing up,” Hudetz said. “John this and John that. Jim Belushi would come to the house and play Santa.”

Hudetz grew up in the Chicago suburb of Naperville. His best friend since first grade was Travis Draft. They were daredevils — sledding down steep hills, ding-dong ditching, racing BMX bikes on the dirt tracks behind the Centennial Beach public pool. Like Sheridan, they also skateboarded — and videotaped themselves. Like Sheridan, they made comedy videos as well.

“Travis would follow me around with a camera,” Hudetz said. “One of my characters was called ‘Rex Braxton, Chick Magnet.’ He’d get off work and come home and fix himself a screwdriver, and he’d call all these girls, and girl after girl would reject him.”

In high school, Draft moved to Jacksonville, Florida. Around that same time, Hudetz started taking classes at Second City. He was 15.

“Chris Farley was an idol for me. I got to see him perform live. And I got to meet John Candy once. He came to Second City. I almost shit my pants. I said, ‘I’m really excited about Uncle Buck.’ That was about to come out.”

When he was 17, Hudetz was sure he was about to catch his big break.

“MTV wanted to do a ‘Real World’-type show with Second City. It was up to Second City to pick the cast. They had an audition and I made it.”

The cast performed at the theater in front of MTV executives. The show didn’t get picked up. Hudetz took it hard.

“I got really down. A few times I thought about quitting the theater. Then Dave showed up. It was so refreshing meeting him. ‘This guy likes putting on thrift store clothes, too. He likes wigs and mustaches.’”

The main thing they had in common — an interest in video — is what most ostracized Sheridan from Second City.

“He’d try and get everyone in his videos,” Hudetz said. “Was always pushing cameras at people while they were saying, ‘No, we’re improv.’”

Sheridan enrolled in a single class at the Chicago Art Institute — Art Appreciation — just so he could have access to the school’s cameras and editing equipment. Hudetz had access to the video equipment at Columbia College, where he was studying drama full-time. He still kept in close touch with Draft and convinced him to move back to Chicago and attend Columbia. Draft majored in film and also took classes at Second City. He and Hudetz lived together in an off-campus apartment.

“Dave would come over and we’d watch each other’s old home videos,” Hudetz said.

“We’d get drunk and high and watch those videos,” Sheridan said. “They were getting electricity from the apartment across from them. The guy’s parents were paying his electric bill so he didn’t care. Frank and Travis had an extension cord running from his place into theirs.”

Together, the three of them further alienated themselves from their Second City peers.

“There was this office-slash-kitchenette that nobody used,” Sheridan said. “It was more the size of a closet. We asked Andrew Alexander if we could use it as an office. He said, ‘Sure,’ and we crammed a couch in there. People were pissed.”

It wasn’t the last time Alexander, Second City co-owner and CEO, would take an interest in the trio.

In the summer of 1994, Sheridan and Draft went to New York to prepare a one-man show Sheridan planned for the theater that fall called “Seven Levels of Love.” (“I can’t remember why I called it that,” Sheridan said. “Maybe cause there were seven characters? And they all had a need for love?”) Draft was to shoot Sheridan on the streets of Manhattan performing different characters. These video vignettes would be shown at Second City. After the vignettes ended, Sheridan would appear onstage as the characters and reveal something unexpected about them.

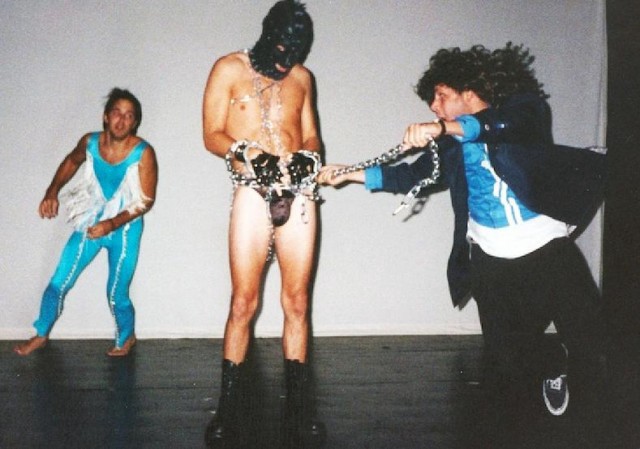

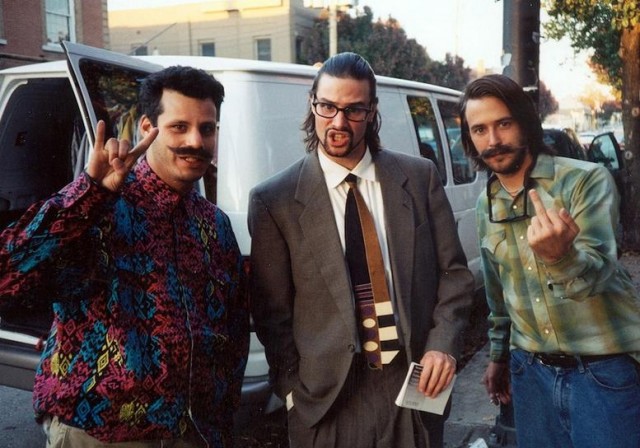

From “Seven Levels”: Photo courtesy Dave Sheridan

“It was pretty much like Borat,” Sheridan said. “We shot it in New York instead of Chicago because I didn’t want any of the locations to be recognizable. And also because I had access to the video equipment at Paterson University. A friend of mine who still went there helped with the filming and checked out cameras for us. We edited there, too. One character was a transvestite. I walked all around Times Square. You know those dudes that hand you fliers for the peep shows? I got a stack of those and handed them out, propositioned people for blow jobs. Then when we went back to Second City and did the show, after the video I’d come out as the transvestite and read beat poetry. That’s what he did on Saturday nights. Another character was a guy who worked at a chicken processing plant. We went to a real chicken processing plant and murdered chickens. Then I’d come out onstage dressed in a Boy Scout uniform. On weekends he’s a scoutmaster.”

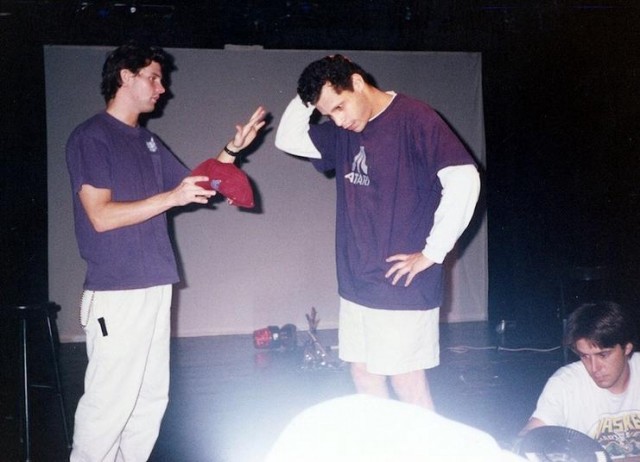

“Seven Levels” Rehearsal: Photo courtesy Dave Sheridan

Hudetz and Draft played several characters in the show’s live portion.

Andrew Alexander was impressed.

“Dave really had a commitment to a character,” he said. “He would do stuff out in the street. I can remember him standing in the street directing traffic as some police character.”

He offered the group $10,000 to film a TV pilot. In return, he’d hold a one-year option. It didn’t win Sheridan, Draft, and Hudetz any more friends at Second City.

“Most people are there for six years before they see any payoff,” Draft said. “The three of us had been there together a year-and-a-half, two years.”

They called the show “Dave Sheridan’s America.” The three of them would drive around the country, interacting in character with an unwitting public and providing not just laughs but a subversive state of the union. Using the same premise nearly 15 years later, Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat would gross more than $260 million worldwide.

For the pilot, Sheridan, Hudetz, and Draft drove to Detroit and back. (Second City had just opened a theater there.) Unlike the New York videos for “Seven Levels of Love,” they used hidden cameras, including a “glasses cam.” This came in especially handy for a segment filmed at the Chicago Bears’ October 2, 1994 home game against the Buffalo Bills.

“I called up the Bears front office and told them we were filming a pilot and said we wanted to film some actors in the crowd,” Draft said. “Somehow they gave us permission.”

That summer, former Bills Hall of Fame running back O.J. Simpson had been charged with murder. Jury selection for the trial was currently underway. Sheridan and Hudetz showed up at the game dressed as Bills superfans. Zubaz pants. Facepaint. And for Sheridan, an O.J. jersey.

“They were pounding beers the whole game,” Draft said. “And cheering, cheering, cheering. Belly-bumping and stuff. Beyond enthusiastic. They wouldn’t stop.”

Draft, dressed normally but for the glasses cam, sat a couple rows in front of the pair. With his press pass, he also filmed their antics from the field.

It wasn’t all juvenile obnoxiousness. In the footage that appeared in the pilot, there are also flashes of the biting intellect and heady improvisation that would come to epitomize the group’s work, as when Sheridan harangues Bears fans, “O.J. can cut to the left. He can cut to the right. And he can cut your throat.”

As anticipated, the Chicago faithful didn’t take the harassment kindly. They screamed “Murderer!” and “Killer!” at Sheridan and soon started pushing and shoving. Eventually he and Hudetz were arrested.

“It was right after Dave had bought a beer,” Draft said. “We were broke as shit, so as they’re putting the cuffs on him he’s still chugging the beer — partly for the camera but also cause he couldn’t afford to let that thing go.”

“They held us in prison for, like, nine hours,” Sheridan said. “This was in the early days of computer scanning. Our fingerprints had to be sent to the FBI to get checked out. And it was Sunday. There was one guy in there who was like, ‘I’ve been in here for five days, man!’ They tried to scrub off the face paint for my mugshot but it just smeared everything purple. My fake mustache was half falling off.”

Andrew Alexander went to MTV with the finished 30-minute pilot for “Dave Sheridan’s America.”

“They liked it,” Sheridan said, “but they didn’t want to do anything with Second City. I’m not sure if they had a bad experience or what. So MTV signed us to a development deal and we moved out to California and just sat around for a year until Andrew’s option ended.”

Alexander remembered it differently: “One night Dave just left for L.A. and took the tapes with him. He never asked. We never had a conversation. It was the oddest thing. I thought about taking legal action. I spoke to an attorney but he said it wasn’t worth pursuing. I didn’t have any paperwork. It was a handshake agreement. I haven’t spoken to him since.”

“I like that story better,” Sheridan said, “but it’s so not even close to the truth — except for us not talking since I came to L.A. I took the tapes of ‘Seven Levels of Love.’ He still had the ‘Dave Sheridan’s America’ tape to sell the pilot.”

Sheridan was 24. He had graduated college before moving to Chicago. Hudetz and Draft were 20 and still in school. But they didn’t think twice about dropping out and moving to L.A.

“This was all I’d ever wanted to do,” Hudetz said. “Here was my chance.”

Travis Draft

Out in L.A., the threesome waited for Alexander’s option to expire. But they didn’t just sit around. On weekends they’d perform a version of “Seven Levels of Love” at Santa Monica’s Upfront Theater, run by a Second City alumni. Their time slot followed another Second City transplant: “Curb Your Enthusiasm”’s Jeff Garlin.

“He did this show called ‘That’s Jeff Garlin,’” Draft said. “It was the lamest show ever. It was just him talking with Larry David, Colin Quinn, and a bunch of other dudes. Boring-ass shit. And it just went on forever.”

One night Draft, Sheridan, and Hudetz finally had enough. Wearing ski masks and carrying fake guns, they stormed the stage yelling, “Get the fuck off the stage!” and pretended to kidnap Garlin.

“Everybody in the audience was clapping,” Draft said.

Even Garlin approved. “That was fucking awesome!” Sheridan recalled him saying. “That’s the way you start a show! You should’ve done that eight weeks ago!”

Finally, the three began meeting with MTV, with Sheridan acting as point man.

“Dave is such an awesome speaker,” Hudetz said. “He can really work a room. They’d have these meetings with all of us, then they’d kick Travis and I out. I really think Dave was the reason the show got picked up.”

MTV first asked them to film another pilot. For one of the skits, Sheridan and Hudetz once again dressed up as football superfans, rooting for the University of Southern California. And Sheridan once again wore an O.J. Simpson jersey. (Simpson won the 1968 Heisman Trophy for the Trojans.) But this time, Draft wasn’t just a bystander. He dressed in a stolen UCLA marching band uniform. Sheridan and Hudetz acted as if they’d kidnapped him — gagging him and binding his ankles and wrists with duck tape — and brought him to the bonfire pep rally before the USC-UCLA football game. They also brought foam baseball bats, which the USC students used to wail on Draft. Then they decided to see just how far the students would take things.

“We had these gas cans we’d filled with water,” Sheridan said. “We started pouring it all over Travis and yelled, ‘Let’s barbecue this fucker!’ Travis was squirming all around and acting like the gas was stinging his eyes. The kids freaked out. ‘No, no way! You can’t do that!’”

Besides the pilot, MTV had a couple other demands. They got rid of the travelogue portion of the show. Each episode would take place in a different city but the trips to and from wouldn’t be filmed. And they asked for a title change. Someone suggested “Guerrilla TV” but that was rejected. Somebody else — no one can remember who exactly — tossed out “Buzzkillers.”

“The head MTV exec loved it,” Sheridan said. “’What’s it mean?’ he asked. I said, ‘A party pooper. Somebody that kills your buzz.’”

“But ‘Buzzkillers’ had already been copyrighted,” said Vince D’Orazi, who worked on the show as a production assistant. “So they made it ‘Buzzkill.’”

“Buzzkill”: Photo courtesy Dave Sheridan

“Buzzkill” premiered on MTV in May of 1996. Along with “The Real World,” “The State,” “Beavis and Butt-head,” “Road Rules,” and “Singled Out,” it was part of MTV’s shift away from music programming. “The Real World” debuted in 1992; “The State” and “Beavis” in 1993; “Road Rules” was spun off in 1995. “Buzzkill” had a less organized and more punk rock, do-it-yourself ethos. Aside from D’Orazi — who also appeared in a few of the episodes — the crew consisted of just a director, a tech supervisor, occasionally a coordinator, and a couple local production assistants. The show’s logo — a happy face in the crosshairs of a gun — was designed by a friend of Sheridan. For the theme song, he commissioned the Columbus, Ohio, band Gaunt, whose recent debut album had been produced by Steve Albini. Then there was the mobile prop closet/escape vehicle: a beat-to-hell white cargo van with a shag carpet interior and silhouetted nude girls on the grille.

Most of the time, Sheridan, Draft, and Hudetz flew between the cities in which they filmed: Miami, New Orleans, Atlanta, New York, Portland, Detroit, Minneapolis, Washington, D.C., Nashville. (Short-lived Western Pacific Airlines was a sponsor, and their planes and crew were featured in the show’s opening credits.) It was D’Orazi’s job to drive the van from place to place.

“It was an incredible job. I was 22 and I got paid to travel across the U.S. But the van had all these registration issues. For the first episode, I had to drive it from L.A. to Panama City, Florida. Took me three days. I had the wrong plates and old registration. But the only place I ever got pulled over, shady as that van looked, was in South Dakota.”

They were there for the annual Sturgis Motorcycle Rally. They had just finished a long day of filming, most of it spent in the desolate Black Hills leading an alien tour and, after coming across extraterrestrial-looking goo, calling in a Men In Black-type squad to decontaminate everyone with a chemical spray (water). In the van on the way back to the hotel, the group — D’Orazi excluded — started to unwind.

“We did some shrooms, smoked some pot, drank some beer,” Sheridan said. “The beer tasted really great. It was so cold and it was a really hot day and we were all sweaty. And we were on shrooms. We got pulled over by the police. They were looking for a white van.”

“They were pulling over every car with California plates cause they thought Hell’s Angels were running drugs into the bike rally from California,” D’Orazi said. “ I saw the car behind us and the lights come on and I’m like, ‘Shit.’ The guys are wasted. The cop comes up and says, ‘Do you know why I pulled you over?’ And I say, ‘No.’ And he says he saw me toss a lit cigarette out the window, which is bullshit. So he has me sit in the passenger seat of his highway patrol car. He asks me if there are any drugs in the car. And I say, ‘No, not to my knowledge.’ He says, ‘You shouldn’t have said not to my knowledge. I’m gonna have to call in the dogs.’ So he calls in the K-9 unit. And they’re going through the van and finding all this weird shit. Wigs, fake mustaches. We try to explain that we’re filming a TV show for MTV. In every other city, people would be like, ‘MTV’s here! Jesus!’ In Atlanta, we hired some off-duty cops for a fake running of the Olympic torch and they were like, ‘Whatever you guys need. You want some streets closed down?’ They even gave us a police escort. But this is South Dakota. They have no idea what MTV is. They don’t care.”

Ultimately the search came up empty and they were free to go.

While part of the reason they picked the cities they did was their wiretapping and privacy laws — in some states, only one party needs to know they’re being filmed, in others all parties need to consent — their choices were also based on live music. “We picked New Orleans because Phish was playing Jazz Fest at the same time,” D’Orazi said. “We picked Atlanta cause the Black Crowes were gonna be there.”

As more episodes aired — holding auditions for a Unabomber musical, dressing up in a Bigfoot costume and scaring hikers — and the cast began getting recognized in public, they also attracted their fair share of groupies. Sometimes so did their alter egos.

In Miami, Hudetz impersonated fashion designer Isaac Mizrahi. Though the two bore an eerie resemblance, Hudetz said he’d never heard of him before the show’s writers proposed the idea. Dressed in Mizrahi’s signature bandanna and crisp white button-down, Hudetz — with Sheridan and Draft posing as assistants — went street casting for a fashion show called “Apocalypse Wow!” Held on the beach, the show featured Miami locals dressed in hazmat suits, bathmats and indoor golf chipping targets.

“There were all these model chicks coming up to Frank and giving him their numbers,” D’Orazi said. “In the hotel afterward there was this one chick who wanted to hang out with him and he was all freaking out, like ‘What should I do?’ Sometimes it was hard to know where to draw the line between work and not working.”

That’s not to say they didn’t take work seriously. To prepare for the Mizrahi bit, Hudetz flew home to Chicago, locked himself in his room, and watched the documentary about the designer, Unzipped, for three days straight. And while the glasses cam might sound easy to operate, it was actually quite challenging. “That was a skill,” D’Orazi said. “You had to be directing in your head — know what framing is.” Usually one segment would take an entire day of filming.

“We wanted to make the show remarkable, so that people talked about it,” Draft said.

One way they distinguished “Buzzkill” from any other hidden camera show that had come before it — and why the Mizrahi groupie might be forgiven her mistake — was by not providing a reveal after each bit. There was no ending in which the actors dropped the ruse and explained that it’s only a TV show, then shared a hearty chuckle with the “marks.” Instead, the three just jumped in the van and sped off.

“We were like Ken Kesey’s Merry Pranksters,” Sheridan said. “Or that Allstate ‘Mayhem’ commercial. We came, we fucked with, we left. This was always a struggle with MTV. They wanted the people laughing at the end.”

That wasn’t the only point of contention. “These guys were writing shit for us that was stupid,” D’Orazi said.

“The writers were not the demographic,” Draft said. “They were older and friends of the producers. None of them listened to punk music or skateboarded.”

The cast did their best to improvise.

“They’d say, ‘You’re gonna blow up a cake at the MTV Beach House and run away,’” Draft said. “And we’d be like, ‘That’s fucking stupid. After we blow up the cake, we’re gonna pants Simon Rex and throw some people in the pool.’”

They also offered suggestions, but few got past MTV’s legal department.

“We had a ton of ideas they wouldn’t let us do,” Draft said. “Like, we wanted to go to Mexico and run across the border with some Mexicans but dressed as marathon runners. MTV put the reins on us big time.”

The higher-ups were particularly concerned about the 1996 MTV Movie Awards, for which Hudetz planned to bring back Mizrahi. He’d be there filming a sequel to Unzipped called Buttoned Up.

“MTV told us, ‘You can fuck with anybody but Whitney Houston,’” Sheridan said. “She was their golden goose. We messed with David Spade, Shaq. We rolled up Shaq’s pant legs and he left them like that. He thought, ‘If Isaac’s doing it, it must be stylish.’”

“At some point, Frank disappeared and wound up hanging out with Whitney’s background singers,” D’Orazi said. “They come walking out with Frank and say, ‘You gotta say hi to Whitney.’ And we’re like, ‘Oh shit.’”

“It wasn’t our fault!” Draft said. “Whitney came to us.”

“She heard Isaac was there and she came to us!” Sheridan said. “We were doing it to show how fake these celebrities are. Like with retakes: We said we didn’t get a shot of her running up and hugging Isaac and asked if she could do it again, and scream louder. And she did. Then one of the producers told her, ‘You know that’s not really Isaac?’ She flipped out.”

“Some asshole from MTV told her he wasn’t Isaac,” Draft said. “If nobody told her, she would’ve been fine and just gone off and smoked some crack somewhere. Instead, she got in her limo and drove off.”

The tape used for the purported documentary was immediately confiscated. (The glasses cam was overlooked, however, and a few years ago the footage surfaced online.)

According to Sheridan, Van Toffler, a top MTV executive, fired them on the spot: “He said, ‘You came in limos. There’s a shuttle bus over there.’” (Toffler, currently president of MTV Music and Logo Group, didn’t reply to an inquiry.)

But the network recanted. “They pulled us into the office Monday morning,” Draft said. “They said, ‘Every time you just push it too far… so we’re only gonna give you 13 episodes next season.’ Our Spring Break episode had debuted with higher ratings than anything they were running at the time. We had ’em by the balls.”

And they acted like it. During a meeting with an MTV publicist, the cast refused to speak to him and threw things at him until he ran from the room. The network acted just as immature, Draft said: “They held the show hostage. We had a schedule to keep to, but the executive producer wouldn’t approve the bits till like the morning we were supposed to shoot.”

On a shoot in the Dallas-Fort Worth area, things finally came to a head. The bit was called “Beef Shake.” Dressed as a cowboy, Sheridan set up a table outside a Whole Foods and offered samples of steak he’d blended into a smoothie. He asked one customer to mind the table while he used the bathroom. The customer repeated Sheridan’s pitch to other customers — one of whom was Hudetz. He drank the shake, fell to the ground, and began convulsing. Also posing as a customer, Draft ran over, informed the gathering crowd that he was a doctor, and asked one of the onlookers to give mouth-to-mouth while he performed chest compressions. As Hudetz spit up the beef shake all over the mark, one of the other onlookers did something that the cast had been encountering more and more: they pulled out their cell phone and called 9–1–1.

“Cell phones were just starting to get popular,” Sheridan said. “Suddenly people could call 9–1–1 right away. Police were always showing up.”

They showed up this time, too. The director shut down filming for the rest of the day.

“We were in our hotel room in Fort Worth,” Draft said, “and I remember looking out the window and saying, ‘Soak it up boys. This is the best it’s gonna get.’ We went back to L.A., got screamed at some more. ‘You guys are giving us no reason to give you another season.’ And that was it.”

The network was so fed up that “best of” compilations were used for the remaining episodes. The final episode of “Buzzkill” ran in fall of 1996.

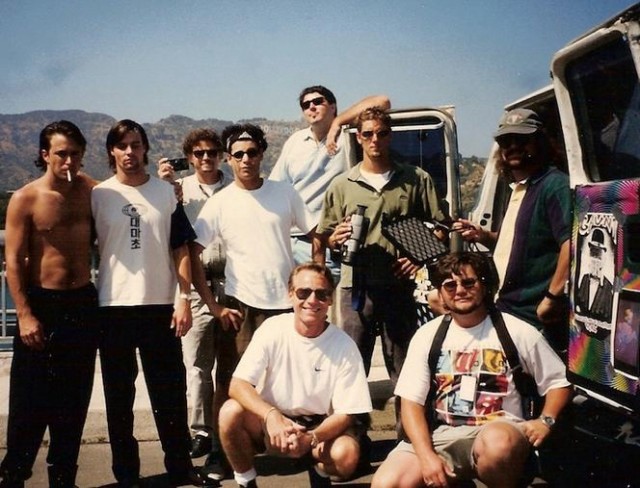

The cast and crew: Photo courtesy Travis Draft

One of the more curious aspects of the “Buzzkill” story is that, despite the MTV brass’s uproar over the show’s lack of propriety, they would soon condone related but far more provocative fare, like “The Tom Green Show,” “Punk’d,” and “Jackass,” which premiered just four years later.

“They were never allowed to take it as far as they wanted,” D’Orazi said, “yet a few years later ‘Jackass’ was taking a dump on people’s lawns. I’m not sure how that was okay and what we wanted to do wasn’t.”

“I heard that was a big mandate by the network,” Draft said. “’Find a show to replace ‘Buzzkill.’ That’s how they came up with Tom Green. I know for a fact Bam and all those Philly guys from Jackass who made the original CKY videos were big fans of ours.”

“They asked me to be involved,” Sheridan said, in “Jackass”: “Bam Margera used to stay at my place whenever he came out to L.A. to skate or do trade shows for Landspeed Wheels. That was my friend Rob Erickson’s company and Bam’s first sponsor. But we were on different trajectories. I was doing some movies and thought that was where I was headed. When it didn’t happen that way, and they took off, there was maybe a little bitterness. I’ll be honest about that. But Borat…. My wheels were sort of spinning in L.A. And this dude is getting all this attention for something ‘new.’”

Sheridan was more amused by the success of his old Second City cohorts — Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, SNL alum Horatio Sanz, writer and producer Adam McKay.

“We were the first to be famous — and ended up the least famous,” he said. “I remember Tina Fey running up to me like a little puppy. ‘What’s it like to work in TV?’ Now she’s a fucking mogul.”

“It happened so quickly,” D’Orazi said. “They felt like they were young and it was their first step — there was nowhere to go but up. Then the balloon just burst.”

In addition to Ghost World, Sheridan has had roles in Rob Zombie’s The Devil’s Rejects and the Wayans’ horror spoofs Scary Movie and A Haunted House.

He’s currently working on a documentary about Van Stone, the now defunct satirical shock-rock band he co-formed with Draft in the early 2000s. Draft was also a founding member of the “yacht rock”-spoofing Knights of Monte Carlo, and he’s continued to be involved in hidden camera shows, appearing in and directing Playboy TV’s “Totally Busted,” Syfy’s “Scare Tactics,” and NBC’s “Spy TV” and “Off Their Rockers.”

Hudetz, too, tried to subsist in show business — for a time. “We all got spit back into Hollywood. Each of us got hit around like a pinball. Me especially. There are guys out there who are 80 and haven’t done anything and they’ve been out there since they were 20.” Returned to Chicago, he’s embarked on a career as a DJ.

“If he hadn’t gotten involved with us, Frank probably would’ve gone through Second City and been on ‘SNL,’” said Draft. “He was that funny.”

While they warred with MTV at the time, they now appreciate just how much leeway they had.

“I dug out an old contact sheet,” Sheridan said, “and out of 34 people on the list, only one had a cell phone and five had e-mail — all AOL. You didn’t have to send anybody the link to the footage immediately. We had a lot of freedom.”

“Looking back after 17 years in the business,” said D’Orazi, who still works in TV, “the whole production seemed fast and loose. Low budget, skeleton crew. We were making it up as we went along. I’ve never experienced a production like it. Totally unstructured. A lot of reality shows today are all mapped out. MTV had to have a lot of faith in them to say, ‘Go do something crazy.’”

Operating pre-Internet allowed more creative control, but it possibly kept the show from achieving greater success. “It might’ve caught on a lot more if there’d been the Web to champion it,” D’Orazi said.

Which raises the great mystery of the Buzzkill story. MTV aired 21 episodes. The “Buzzkill” account on YouTube has all of three videos, and apart from a couple other videos, there’s just nothing out there. Compare that with another 90s MTV comedy, “The Idiot Box,” created by and starring Alex Winter of Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure. Though only six episodes aired, clips from each are available on YouTube.

Sheridan is happy about the scarcity of “Buzzkill.”

“Everything’s online. There’s nothing special anymore,” he said. “Plus, your memory of the show is better being your memory in that period. Our core audience was 13- to 16-year-olds. If you watched the show now, it probably wouldn’t hold up. And so much has been done since. It probably wouldn’t hold up to the Funny or Die audience.”

But what about MTV not possessing any of the footage? Do they have any idea how that happened? What of the speculation that “Buzzkill” was behind it?

They all claim innocence.

“I heard all the master tapes went missing,” Sheridan said. “But I don’t know how. It’s a Buzzkill.”

Sean Manning is the author of the memoir The Things That Need Doing and editor of several nonfiction anthologies, most recently Bound to Last: 30 Writers on Their Most Cherished Book. He also edits the blog Talking Covers.