Our Radical Future: Cults, Utopias and Rebellions of the 1890s

by Jacob Mikanowski

Women and prisoners of war from Canudos, Flávio de Barros, 1897

Canudos, the holy city. From the hills it had looked like a mirage. Fifty-two hundred mud huts and a handful of white-washed churches spread along a bend in the Vasa-Barris, where a few years before there had been only a ruined farmhouse and an old well. The walls of the houses were the same shade as the parched earth on which they stood, so you could barely see the town until you were already in it. For the last ten months of the city’s life, it been bombarded by a full division of the Brazilian Army. Thousands of its defenders — the half-cowboy, half-bandit jagunços — were dead. They had been shelled by artillery from the mountains and gunned down by machine guns on the plains. When the fighting moved into the city itself, they fought house to house and door to door, using piles of corpses as barricades. Their leader was dead. Dysentery claimed him in the night. Hundreds had died in the weeks since. The end was at hand. On October 5, 1897 the Army made its final assault on the town. They found four combatants left in the trenches: two adults, an old man, and a child. They died where they stood. Canudos was no more.

Euclides da Cunha, an engineer and journalist embedded with the troops, nicknamed Canudos the “mud-walled Jerusalem,” but to the people who lived there, it was Belo Monte, the beautiful hill. When the soldiers of the Brazilian Republic finally took the city, they burnt every house, one by one, and pulled down all the spires. Then they cut the throats of all the male prisoners, including the children, and sold the women and girls to the brothels on the coast.

Finally, they dug up the body of Antonio Conselheiro, Antonio the Counselor, maybe to make sure the Messiah of the Brazilian backlands was dead. They cut off his head and sent it to Salvador, where it was met by a jubilant crowd. Doctors studied the skull for abnormalities, after which it was placed in a museum.

The photograph above shows prisoners from Canudos. It might be the first photograph of refugees, ever. It was taken just before the end of the siege by Flavio de Barros, a journalist embedded with the Brazilian Army. Barros’ equipment wasn’t very good. His pictures are scratched, damaged, and blown out by the force of the tropical sun. In this photo, the blurriness comes from the slow exposure time. Inadvertently, he caught the adults’ restlessness, the fidgeting of the children. We can’t know for sure if they are aware of what’s coming, but it’s a safe bet that they’re afraid.

The apocalypse they had been promised was different. It was supposed to be an end to poverty, an end to hunger, an end to drought, an end to property and rank. They were going to inherit the earth. For a time, it had even felt as if they had.

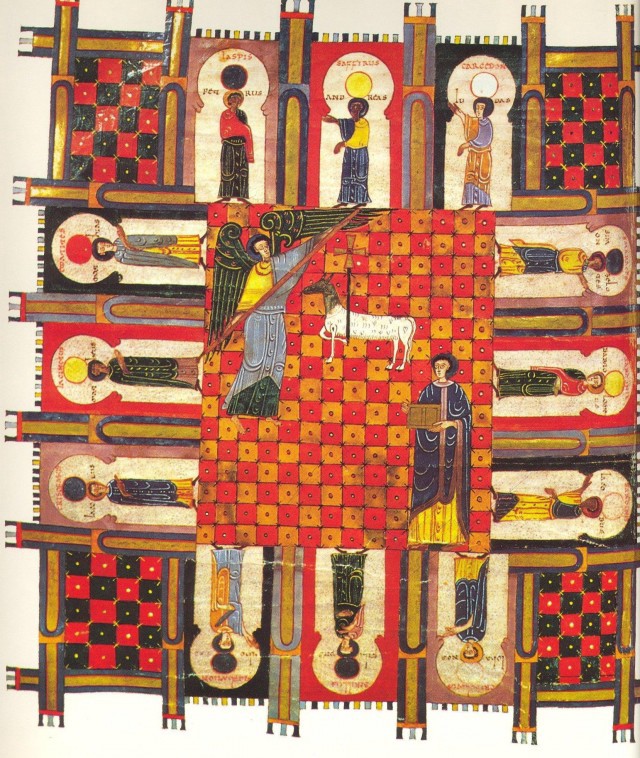

The Descent of the New Jerusalem, 14th century tapestry

(Read later with Pocket.)

Canudos came into being because of a dream. It was a dream of utopia and a dream of escape. It was an ancient dream: the earthly Jerusalem, the heavenly city. And in the 1890s, it was shared by the dispossessed and marginalized the world over: by the inhabitants of Canudos in the drought-raved backlands of Brazil, by the anti-foreign Boxers in northern China, by the half-ecstatic, half-despairing practitioners of the Ghost Dance in the American West. All of them, in their separate ways, were searching for space and the means to remake the world over in their image.

The 1890s were a time of starvation and revolt. It was a decade of environmental catastrophe, economic depression and savage colonial wars. It was also the golden age of liberal capitalism and global imperialism, a time when the combination of industrial manufactures and Western arms had penetrated almost every corner of the world. In the 1890s, most people still lived on the knife-edge of subsistence, stalked by the threat of drought and flood, boom and bust. In his book Late Victorian Holocausts, Mike Davis argues that the El Niño-driven famines that characterized this era, exacerbated by political forces, helped to create the Third World. Climate oscillations put millions in jeopardy, while new technologies reduced them to the status of laboring machines and made armed resistance seem futile. In response, people pursued politics by other means. Messiahs and prophets walked the land offering fiery predictions and magical cures. Their movements confronted despair with millenarian longing. Their methods combined mysticism with violence.

In the United States, the 1890s are an almost forgotten time. The whole stretch of American history between the end of the Civil War and the 1920s is gray area in popular memory, but the 1890s are especially blank, occupying a dead zone in between “Deadwood” and “Boardwalk Empire.” The decade lacked wild frontiers to mythologize or heroes to emulate (which might be why no one remembers it). Instead, the 1890s were marked by ferocious class hatreds and savage industrial strife. In Pittsburgh, a strike at the Homestead Steel Works turned into an all-out war between union members and the Pinkerton detectives sent to break them. In Johnson County, Wyoming, big ranchers fenced off lands which had once been held in common. When small farmers refused to leave, the ranchers hired mercenaries to kill them. In 1893, a banking panic set off a four-year depression, the worst the country had known until that time. One in five industrial workers was unemployed. Groups of men in the West banded together into tramp armies, overpowering railroad guards and riding trains for free in search of food. In the East, they rallied around a man named Jacob Coxey, who led an army of them to Washington to ask for work.

Charles Koehler family in front of their farmstead, c. 1890, Charles J. Van Schaick

Michael Lesy captures this world in his book Wisconsin Death Trip, which uses photos and newspaper snippets from Black River Falls, Wisconsin to tell the story of a rural community consumed by disaster, epidemic, and despair. As agricultural prices fell and farmers could no longer pay their mortgages, families moved out or succumbed to destitution. Lesy writes: “By the end of the nineteenth century country towns had become charnel houses and the counties that surrounded them had become places of dry bones. The land and its farms were filled with the guilty voices of women mourning for their children and the aimless mutterings of men asking about jobs.”

Some people hung themselves, some went insane, and some fled to the cities, but for the most part, the American response to these blows was political. Working people agitated for full employment and loose silver. They organized in unions and voted for the Democrats. But then, they had practice. Politics was an American habit.

In other parts of the world, places where literacy was rarer and rights newer, politics took on different forms. In Sicily, socialism was received by the landless peasants of the interior as if it was the true teaching of Jesus Christ. A peasant woman from Corleone (where Vito came from in The Godfather) told a delegation: “We want everybody to work, as we work. There should no longer be either rich or poor. All should have bread for themselves and for their children. We should all be equal…,” she said: “Jesus was a true Socialist.”

Further afield, the response of local people had less to do with parties and more with prophecy, magic and war. In Northern Sudan, Arab people rallied around their own Messiah, Muhammad Ahmad — the Mahdi — whose army drove out the Egyptians before killing General Gordon at the Siege of Khartoum. His followers believed that he could turn enemy bullets into water. A few years later, the Maji-Maji in Tanzania became convinced that their war medicine (a mixture of water, castor oil, and millet seeds) had the same power, as they did their best to slaughter the German settlers who had taken their land. In Zimbabwe, the spirit mediums of the Mwari cult promised that the rains would return as soon as the white men were driven out. In the Philippines, thousands of sugar plantation workers fled into the hills, led by charismatic miracle workers, which included an eighty-year-old woman who called herself the Virgin Mary and a transvestite who claimed to control the weather.

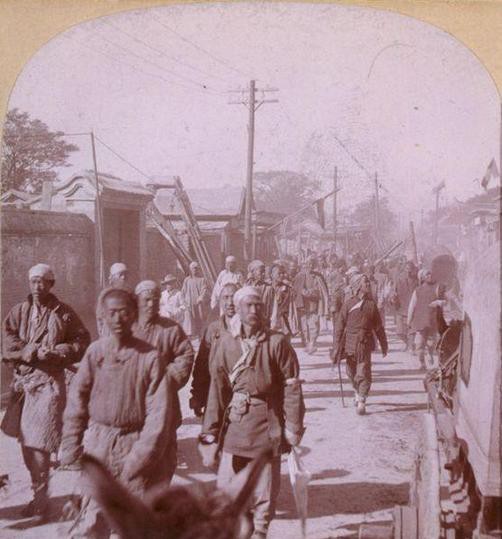

Boxer Militia, 1898

In China, the forces of famine, folk religion and hostility to foreigners coalesced to create the most spectacular conflagration of all. At the end of the 1890s, in the drought-stricken provinces of Shandong and Zhili, bands of landless peasants organized together in martial arts societies. They became convinced that Christians, both Chinese and foreign, were harming the geomantic currents in the earth, causing drought and floods. The churches had bottled up the sky. Fearing starvation, at odds with the government and outgunned by the Western powers, the Boxers turned to the only instrument at their disposal — their bodies. They believed in the discipline of body and of breath. With sacrifices and spells they invited spirits to possess them. Once possessed, they behaved as if they were drunk or in a dream state. They felt themselves to be invulnerable to bullets. Like the dervishes and Maji-Majis, they fought courageously and recklessly, winning many victories on the road to total defeat.

America had its own messianic movement aimed at negating the circumstances of the present, although with prophecy in place of bloodshed. In Nevada, a Paiute man named Wovoka (he also went by Jack Wilson) fell into a trance during a solar eclipse. When he woke up, he was a prophet. He told his followers that Jesus was now upon the earth, “appearing like a cloud.” A golden age was coming. There would be no more sickness. Whites would make peace with the Indians and everybody would be young again. Game would return to the land, and so would the dead. Wovoka taught his people the ghost dance, which they believed would bring their ancestors back to earth. He said that while they waited, he would be God’s deputy in the West, just as Benjamin Harrison was in the east.

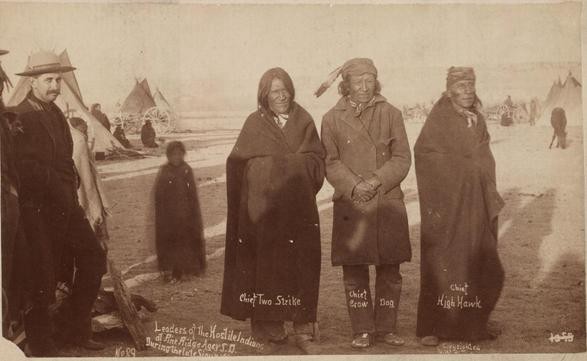

Chief Two Strike, Chief Crow Dog, Chief High Hawk, Pine Ridge Reservation, L.T. Butterfield, 1890

The Ghost Dance spread across the tribes of the American West, taken up in turn by the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Caddo, Kiowa, and Pawnee. The Sioux went furthest in embracing the new religion. Like many of the Western tribes, they had recently lost their land, as well as the land that had been given as compensation for that loss. After a dry summer, they were at risk of starvation. In the fall and winter of 1890, they gathered by the hundreds to dance. They wore ghost shirts, which would make them (yes) invulnerable to bullets. Their numbers frightened some of the resident Indian agents. They thought Sitting Bull was in charge of the movement. When they went to arrest him, they shot him instead. Next, they tried to disarm the Miniconjou chief Big Foot’s band. A shot went off, and the Army began to fire, training rifles and machine guns both into the crowd. A hundred forty-six Indians died, mostly women and children. Now the land is for sale.

The Ghost Dance was a religion of peace, a way of cultivating hope in the face of defeat. The dance itself was ecstatic, apocalyptic, a bit frightening — but a dance all the same. A doctor on the reservation remarked before the massacre, “If the Seventh Day Adventists could put on strange robes and perform rituals in their wait for the coming of the Messiah, why shouldn’t the Sioux be granted the same license?”

Like the Ghost Dance, the story of Canudos began with a dream and ended in a massacre. The dream belonged to Antônio Conselheiro, a shopkeeper’s son from the Sertão, the semi-desert scrubland of Brazil’s Northeast. Like most inhabitants of the backlands, Antônio’s family suffered from drought, the oppression of landowners, and hereditary feuds. For a time, he worked as a salesman and a tutor. Then his wife left him and something broke. He withdrew into the country and had visions. He lived like a vagabond and a tramp. For twenty years he wandered the backlands preaching, restoring churches and ministering to the poor. With his long tangled beard, emaciated face and piercing eyes, he looked like Elijah in a blue canvas robe. Thousands would gather to hear him speak. When the Brazilian Republic was established in 1889 (until then, Brazil had been an Empire, ruled by the heavily bewhiskered Pedro II), the new regime struck him as an abomination, godless and absurd. He spoke out against inequality and slavery (only abolished in 1888), and predicted the days when the backlands would turn into the seacoast and the seacoast into the backlands.

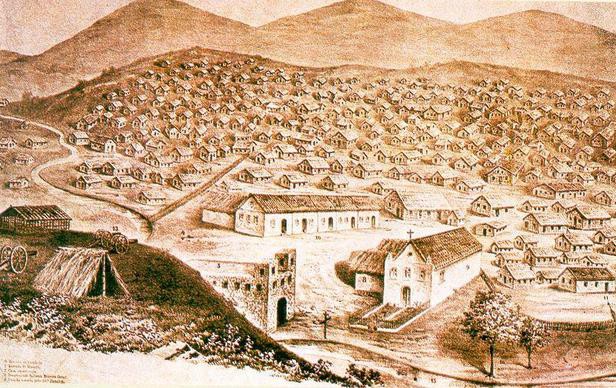

Canudos, Flávio de Barros

In 1893, Antônio settled with a handful of followers on an abandoned farm in Canudos. They were squatters on land belonging to the richest landowner in the province, the Baron of Jeremoabo. Northeastern Brazil was a lawless place, and desperately poor. Less than one percent of the inhabitants owned more than the clothes on their backs. In the 1870s, drought had killed a million people. At the end of the 1890s, it killed a million more. For the dispossessed, Canudos acted like a magnet. From across the Northeast, landless peasants and former slaves streamed into the Holy City. There they were joined by backland cow drovers and uprooted Kiriri Indians, and even a few bandits. By 1897, Canudos had grown into a town of 30,000 people, the second largest in the province.

For a few years the experiment flourished. The city was run as a communitarian theocracy, with rule by apostle. Property was held in common. Money and alcohol were banned. Businessmen moved in, setting up a thriving trade in leather with the coast.

This is the part of the story where I would normally explain that it was all really a cult, that Conselheiro was a fanatic, and that his movement was really about self-aggrandizement or sexual control. That’s generally the case with charismatic movements and self-contained utopias. From the beginning, millenarian movements, no matter how egalitarian, have been afflicted by a creeping Jim Jones-ism: megalomania among the leaders and subservience in the followers, all leading up to catastrophe in the end. But that doesn’t seem to have been the case in Canudos. While the city grew, Conselheiro kept doing what he had always done: preaching and building churches. He left the day-to-day administration of the town to his deputies, the apostles. He was treated like a beato, a holy man, but he didn’t take on airs. ‘The Counselor’ was just a nickname. Conselheiro always referred to himself by his given name, Antonio Maciel. From the outside, it looks as if he made good on his promise. He returned the church to its communal roots, and built a place where race and class didn’t matter.

Canudos in 1895, by an unknown painter

But then again, it’s hard to know exactly what happened in Canudos. For the most part, we have to rely on the testimony of their enemies. Our main source is Euclides da Cunha, the journalist who accompanied the invading army. The war moved da Cunha to write his epic account Os Sertoes (Rebellion in the Backlands), a masterpiece of engaged nonfiction but a work so riddled with contradictions it’s hard to take as a direct account. Da Cunha was an engineer, a soldier, and a bit of a dandy. He stood for the Republic and for progress. Canudos was everything he opposed: fanaticism, superstition, monarchy, backwardness. But it was also a puzzle, and he threw everything at his disposal at solving it, from anthropology to geography to history. He tried to locate the origins of Canudos in the harsh landscape of the backlands, in the hereditary imbecility of its people, and the history of religious manias.

It’s easy to get seduced by da Cunha. His language is unhinged and magnificent. He tries to explain everything, down to the bedrock he’s standing on, yet he always cycles back to his own confusion. The motives of Antonio’s followers mystified him. Their beliefs were repellent. But knew that what the army was doing was an obscenity. Throughout The Backlands da Cunha behaves like James Agee in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, agonizing over his relationship to the Gudgers, wondering if he should be there, if he should be writing this. You can feel da Cunha’s anguish soaking through the curlicues of his Baroque prose. The harder he tries to make sense of what he sees, the more his metaphors proliferate and spawn: Canudos is an “an unconscious brute mass… without organs and without specialized functions in chaotic layers reminiscent of a human polyp.” Conselheiro’s cowboy defenders are “truculent John the Baptists, capable of loading their homicidal blunderbusses with the beads of their rosaries.”

Body of Antônio Conselheiro, Flávio de Barros

The war that brought an end to Canudos started as a dispute over trade. The apostles bought some lumber in another town to use in the building of a church. A local landowner confiscated it — revenge on the holy city for luring away his workers. The police were brought in. The quarrel escalated and shots were fired. An army expedition was sent to bring Canudos to heel. It was beaten back. So were two more. Panic started to set in throughout the country. If a bunch of primitive backlanders could hold out against the full power of the state, the Republic was doomed. Finally, a whole army column was sent to destroy the town once and for all. That ten-month siege began, a terrible war, in which the aggressors suffered nearly as much as the besieged. Conselheiro spent his last days in communication with heaven. According to legend, his last vision was of Jesus Christ, blown up by a grenade.

So what was Canudos, really? Everyone who writes about it finds what they expect. Da Cunha saw hysteria and mass delusion. Mario Vargas Llosa, in his novel The War at the End of the World, saw a story of dueling fanaticisms. The historian Robert Levine sees a rational response to social change, rooted in Orthodox Catholicism. Slavoj Žižek sees a precursor to Communism, in line with his own ideas of a radical faith. The same problems of interpretation crop up with the Boxers, the Ghost Dance, and all the others. Messianism is a language that’s always spoken in the vernacular, and easily misunderstood. To Marxists, charismatic movements seem primitive. To liberals, they’re fanatical. To the orthodox, they seem heretical. And to those predisposed to put faith in revolution and resistance, they can seem like glimmers of utopia. All too often, charismatic and millenarian movements are dismissed as anachronisms, suffering from what socialist historian E.P. Thompson called the “enormous condescension of posterity.” Just as frequently, they can be used to ventriloquize the politics of the moment, and fulfill our own sense of what’s just and unjust.

The New Jerusalem, Illuminated Manuscript (Spain), 1047

So who’s right? My instinct is to listen to the people themselves, but the burning (and subsequent dynamiting) of the city left little trace of what they thought. There are a few exceptions though. Before the city fell, a young captive was taken to Salvador to be interrogated by officers from the Brazilian army. They expected to hear stories about miracles and visions. They asked him what Conselheiro had promised his followers to convince them to die for him. The answer was simple: “To save our souls.”

A few sermons and poems were recovered from the ruins of Canudos. One of them reads: “Backed up by the law/Those evil ones abound/We keep the law of God/They keep the law of the hound.” What does that mean, the law of the hound? It’s the law of the wolf, the law of the strong. Whether or not the Canudense believed in a messiah or were fighting to bring about the end of days, it seems clear that this is what they were trying to escape. The laws were terrible, so they found a way to live outside those laws. They came to Canudos in search of salvation, but they also arrived in search of autonomy, and of dignity. They became masters of the art of not being governed. Their achievement was brief, but real. And if in the end they failed, the failure wasn’t their own. Even if their project began in a dream, the city they created was real, and it was a failure of imagination on the part of the powerful that brought about its destruction.

Canudos Burning, Flávio de Barros

But then again, maybe success and failure, delusion and reality, aren’t the right yardsticks for measuring utopia. At the start of The Stammering Century, his history of the radical movements, religious cults and utopian communities thof 19th century America, Gilbert Seldes writes that even though many of the figures he describes were ridiculous, “ridicule failed to touch them…. What made them important is what they did and the various ways in which, from time to time, they laid hold on the imagination of a group, or community, or country.” Utopias aren’t political programs; they’re attempts to find the limits of what’s possible. They crystallize aspirations and create a bulwark against despair.

That might be something worth remembering now that the 20th century has run its course. The ideological wars that dominated it, between liberalism and fascism, communism and capitalism, seem to be mostly settled. Smaller battles have taken their place. In many ways, we’re returning to the world of a hundred years ago: a hot, dry place, where political questions revolved around water and bread and protection from arbitrary force, with Global Warming in place of El Niño and Predator drones instead of the Maxim gun. And as the world gets hotter and drier and more unpredictable, maybe we shouldn’t be too quick to flinch from the glare of magical thinking and extravagant belief. This past is our future. So for the time being, let’s not focus on the defeat and the slaughter, and instead freeze the frame a moment before, on the ecstasy of dance and the refusal to be ruled.

Jacob Mikanowski writes about art, books and Europe east of Berlin.