Killer Cops And Newspaper Wars On The California Coast

“America’s largest open-air mental hospital,” that’s how Oceanside police spokesman Bob George described this run-down coastal city between Camp Pendleton and the surfer towns of North San Diego County. I called it the Slum by the Sea. Despite the miles of beach and the beautiful old Spanish mission and the Southern California weather, Oceanside was a honky tonk Marine Corps town on the west side of Interstate 5 and a sprawling mess of trailer parks and starter-home suburbs to the east.

I spent a lot of time at Bob’s desk in the back of the OPD headquarters. Sometimes it was as a police beat reporter, sometimes it was as the City Hall reporter chasing the latest on the endless war between the crooked mayor and the corrupt police chief. The paper had been called the Blade Tribune when I managed to get a job on the copy desk after many tries, and it was the Blade-Citizen by the time I became a reporter. A dirty shore town between Tijuana and Los Angeles had everything the Blade needed to fill its broadsheet-sized daily with tabloid soul: a massive Marine Corps base to supply fights and drunks and war casualties, an infamous white supremacist in the avocado hills, Samoan street gangs, Mexican drug runners, redneck cops, amateur mafia routines on the City Council, Vietnam-era explosives about to blow up the whole town, a boobs-shaped nuclear plant on the beach and always on the verge of meltdown, surfers vs. jarheads, Reagan vs. the homeless who stopped at Oceanside because that was the edge of the country. The publisher sponsored surfing contests and paid for psychics to search for missing kids. It was magnificent.

It was also a full-blown newspaper war, with four dailies competing for stories and subscribers: Helen Copley’s San Diego Union-Tribune, the North County Times-Advocate, the expansionist Los Angeles Times’ San Diego edition and the terminally understaffed and underbudgeted Blade. A half-dozen television news teams, radio newsrooms and wire service bureaus rounded out the San Diego County competition, along with dozens of weeklies and twice-weeklies and the big guns in Los Angeles that would always appear whenever we got another grisly murder or cop scandal or mayor going to prison or natural disaster.

It was the mad genius Tim Mayer who plucked me from the copy desk when the Blade-Tribune was still an afternoon paper. The PM dailies were fading by the end of the 1980s, and they attracted a talented bunch of drunks, bums and burnouts. We started work at six in the morning and put the last editions to bed by early afternoon. Tim was the city editor, and I worked the slot next to him in the fantastically ruined newsroom of worn-through carpeting and curving 1960s’ desks and nicotine-stained computer terminals connected to an unreliable mainframe we all called “Mother,” with equal parts respect and loathing. Tim had been a Navy SeaBee, one of the maniacs who cleared the ever-changing frontlines in Vietnam with bulldozers, before the infantry. He had a walrus mustache, wore a tie and suspenders over his striped dress shirts, and inhaled huge amounts of snuff from his top desk drawer. He would lean over the kit, take a loud snort, then raise his arms in victory and slam the drawer shut. I had never seen anyone do snuff. My first few weeks on the desk, I assumed this manic ritual was for cocaine.

The terrible Italian restaurant directly across Hill Street from the newspaper’s 1970s beige-block headquarters was the natural place to go after another day’s work. But I lived 25 miles down the interstate in San Diego and deeply feared the CHP, so I kept my after-work drinking to a minimum. Instead, I worked hard — editing the next day’s stories, volunteering to write stuff for the features section, reading endless wire stories from Washington and New York and Moscow to teach myself about the current batch of people who ran the world. That wire-service education proved extremely valuable when the Berlin Wall came down during my time on the copy desk. But it shortened my daily newspaper career, too: I was standing at the wire-photo machine when those first images of people dancing on the Wall inched out, looking like stills from the video for “Radio Clash.” Too much was happening. Before the Soviet Union collapsed, I would be living and working in Central Europe.

But first I needed to become a daily newspaper reporter. I assembled my unimpressive clips and gave them to Tim, who glanced over them with dismissive grunts.

“I’m not hiring you because of these,” he said as he pushed the slim stack of Xerox copies back at me. “It’s because of what you’ve done here on the desk. Do that on your beat.”

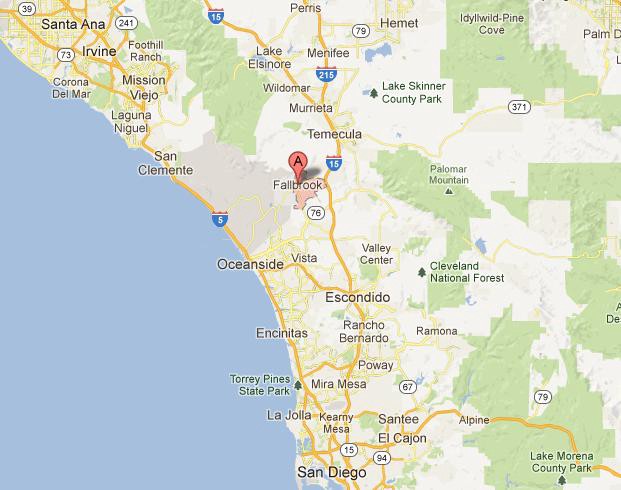

The beat in question was Fallbrook, an avocado and citrus town at the very edge of the Blade’s range. It was a beat close to Tim’s heart, because he had it himself years earlier. So did my friend and hero Terry Wells, who now covered City Hall and would burst into the newsroom in a cloud of smoke, his lone necktie hanging askew over a wrinkled short-sleeved shirt, talking so fast and in such arcane detail that nobody was sure what his story was about, but it would be huge, and was definitely front-page material, above the fold, just give him a few minutes. Terry’s ex-wife ran the copy desk, and she would watch him with a mixture of affection and revulsion. They somehow shared the duties of raising their daughter and only fought very quietly in the back corner of the newsroom.

As an official staff writer, I was given a “Trash 80” computer for filing remotely. These things were made by Tandy and sold by Radio Shack. The display was a narrow liquid-crystal rectangle that showed exactly what I needed to see: the sentence I was typing. There was a modem on the city desk and an occasionally functional way to call in from any phone line and dump your copy to the system. But it worked best if you were already in the newsroom, so most nights in Fallbrook I would drive the winding country road back to Oceanside, file my stories, and then drive home to San Diego. A hundred miles of driving a day was normal, and I have always loved driving. There was a micro-cassette recorder called the “Devil Box” on the dashboard, ready for mobile dictation, and several rolls of quarters in the glove box for dictating stories straight to the city desk by pay phone.

I covered all the usual meetings and events: the Avocado festival, county land-use hearings, the Farm Board, the new suburbanites complaining about the smelly old agricultural economy, and the antics of White Aryan Resistance founder Tom Metzger. It was the beginning of the militia movement in America, with laid-off defense contractors and bad cops relocating to the rural fringes of the West and congenitally dumb exurban skinheads looking for a religion to match their racism. Metzger was a perfect clown for this scene. W.A.R gave Geraldo Rivera a broken nose on daytime TV, Metzger ran for Congress as a Democrat, he was sued by the Southern Poverty Law Center, and he had enough publicity smarts to keep himself in the local newspaper.

One afternoon in his corny country kitchen, his wife dead from cancer and his house lost in the civil trial over W.A.R. skinheads killing an Ethiopian immigrant in Portland, Oregon, he began a rant about The Jews.

“Tom, you know my wife is a Jew,” I said. During a very brief marriage, my reporter wife had joined the staff of the Blade and was covering the courts beat, which included covering Morris Dees’ very effective strategy of suing W.A.R. out of existence.

“Oh, Stacy’s all right,” he said. “She’s a good Jew.” Metzger was not very good at being anti-Semitic or racist, in the end. He made excuses for every minority or Jew he personally knew.

The paper switched to morning publication within weeks of my ascent to the Fallbrook beat, and the disgustingly charming old newsroom was soon replaced by a sterile high-ceilinged warehouse of new cubicles like you’d see in an insurance office. “Mother” died by assisted suicide and powerful Sun workstations appeared on our shiny new formica desks. The resident computer genius, a shabby black-goateed and motorcycle-booted Harley rider named Ernie, had convinced the publisher to outfit this newsroom with the very best desktop publishing system, including these powerful Sun boxes for reporters who only needed the most basic word processor. But these graphics powerhouses were fantastic for pranking people on deadline — my favorite little program would make everything on the screen deteriorate and flake away, like reality itself crumbling. You could set this to run at a certain time, and it really did have the power to make the hardest reporter shed real tears. Computers were still so mysterious. Ernie would have to come out of his server-room hole and restore the screen and try not to laugh.

There weren’t a lot of front-page stories in Fallbrook, so I muscled in on any big news that needed an extra hand. Then I teamed up with the county government reporter, a deadpan character from Stockton named Harry Fotinos, and we won a bunch of state and local press club awards for a series on agriculture. He won an entire fake Victorian house from the city of Oceanside when he bought a raffle ticket on a whim, and the crooks on the City Council despised him because he worked for the hated Blade.

I learned pretty quickly how to write for the press club judges — just follow the pretensions of the Los Angeles Times “Column One” features and you could get an award for any old horseshit. (One of these prizewinners was literally about horseshit. Harry and I wrote some “times are changing” pathos about a battle between the residents of a new suburb and an organic mushroom farm run by righteous hippies who fed their crop a steady diet of manure from a nearby racehorse farm that served the Del Mar track.)

There were promotions and raises, and my natural dislike of cops made me a good match for the police beat. I covered Oceanside’s old-boy cops and then moved on to the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department, a right-wing fear machine run by Nixon crony John Duffy. An old Navy cleric who served in Vietnam got roughed up by a couple of instant redneck deputies outside his house in the North County suburb of Vista. He was outside trying to help some people who crashed on a hairpin turn, and the deputies beat the hell out of him and tossed him in the county jail. I covered the civil trial, and was delighted to report that James Butler had won $1.1 million in what was then the biggest cash award for being a victim of the sheriff department’s brutality.

Around this time I began getting the phone calls late at night, the gruff warnings to watch my back and make sure to check my brakes. I wasn’t sure if it came from the violent idiots at the Oceanside police department or the furious deputies put on leave for their various crimes against humanity, but I was glad to be living within San Diego city limits and outside the range of the sheriff and OPD.

John Duffy had suddenly retired after 20 years of mob entanglements, homophobia, corruption and liberal-baiting stunts, rather than face one of his own captains in the 1990 election. Upon quitting, the forever-agrieved Texan bully said, “The power of the media in this country is awesome and is a threat to every American.” He dropped dead of a heart attack three years later, at 62, while on a fat consulting contract for the policia in El Salvador.

Jim Roache was the captain running for Duffy’s job, and I liked him because he was young and friendly and mostly because he wasn’t Duffy. He met the editorial board at the paper and gave a good outsider’s pitch. The feuding brothers who ran the Blade as publisher and editor-in-chief, Tom and Bill Missett, always liked the underdog. I think we endorsed Roache, but the value was questionable after I broke a front-page story about Roache choking an inmate to death in the North County lockup.

Still, Roache won. I was at Golden Hall in downtown San Diego where the press always gathered on election nights, and I vaguely recall dancing with Roache’s wife after the race was called. Objectivity has never been my strength. I wouldn’t see either of them again until the funeral of a deputy shot dead by another deputy in a bizarre home-invasion robbery involving pistol whipping, diamonds, drugs and somebody’s elderly mom tied up inside an Encinitas beachside mansion.

Back when monitored home burglary alarms were rare enough that the cops actually responded to break-ins, a sheriff’s deputy had burst into this house to find a masked villain threatening to kill the old lady and her adult son. The deputy fired, and when he pulled off the mask he found… his fellow deputy from the same sheriff’s substation. The dead deputy forfeited his official Sheriff’s Department funeral by being killed in the commission of multiple felonies, but he was still a Navy veteran and would get that military ritual at the veterans’ cemetery on San Diego’s Point Loma. The press was barred from attending. Marines guarded the chapel and its parking lot.

That I looked and dressed like a cop is just one of those mysteries of life. On the day of the funeral, I stripped my pickup of press stickers and press cards and drove to the funeral. When asked, I told the teenaged Marine guard I was a colleague of the deceased, which was true in its own way. In my aviator sunglasses and Navy blazer, I entered the chapel and was greeted by a deputy dressed in nearly identical civilian clothes. It took me a moment, blinking in the dark and silence, to realize his eyes were welled with tears and that he seemed to recognize me, but the details of his memory were wrong. I was not a fellow cop, but I hugged him back just the same.

He handed me off to another stone-faced deputy in a coat and tie, and this designated usher led me to a pew near the front. I slid down the bench next to Mrs. Jim Roache, the new sheriff sitting beside her. We were instructed to hold hands and pray, and I prayed she wouldn’t recognize me. If she did, nothing was said. When I got back to the newsroom in Oceanside, comrades were watching the TV over the city desk and laughing. The longshot video from the edge of the parking lot showed the sheriff and various deputies streaming out of the chapel. I was walking down the steps with the rest of them, trying to get my sunglasses on before any more eye contact occurred.

What else was left to do? A war began, in Iraq and Saudi Arabia, and because I had also worked the Camp Pendleton beat I lobbied for a Saudi press visa and was scheduled for a cargo plane flight out of March Air Force Base to the massive Pentagon encampment on the border with Saddam’s Iraq. Once there, I would hire a car to Israel or Lebanon and begin my foreign corespondency. But the first Gulf War ended so quickly that my press pool never happened.

I didn’t care too much about reporting but I had a natural ability to write the stories the Blade needed for the front page, day after day. I could pick one of these out of a half-heard conversation at City Hall or the coffee shop where the old guys would gather to talk about the latest corruption scandal in the works, and I’d have the required 12 inches of copy by deadline that same day. My salary was just shy of $25,000 a year, the top of the non-union pay scale for reporters. A recession had already begun in Southern California and would be the latest excuse for newspaper hiring freezes and layoffs and the already destined collapse of that whole industry. I got an interview or two, but lost the jobs to people with Ivy League degrees in journalism. Out of boredom I put together a honky tonk band and we played the Belly Up Tavern once a week, and I wondered, like I would periodically wonder, if I’d chosen the wrong profession, if I just didn’t have the social standing or education for American journalism.

Then I got the chicken pox and nearly died. Do not get the chicken pox when you’re 25. No doctors would even see me, because there was nothing they could do, but one did kindly inform me by telephone that sterility and blindness were possible outcomes. Sterility would be fine, but I needed my eyes. When the month-long fever haze of this terrible childhood disease finally faded, I looked at my pox-scarred face and said, “It is time to get out of this country.” A few months later, after selling the pickup to the guys at Alberto’s Taco Shop for their avocado farm just across the border in Mexico, I was in Central Europe. The Iron Curtain had collapsed but the U.S.S.R. was still hanging on. I never worked for a daily newspaper again.

The four-paper news war ended a long time ago in San Diego County. The L.A. Times abandoned its local edition first, and then the Blade merged with the Times Advocate, and the U-T finally subsumed the remains of the North County competition. The Blade’s old headquarters on South Hill Street in Oceanside was abandoned years ago. The only part that still lives is the weird news collection I loved to edit more than anything on the copy desk, the back of the A section. It was called, simply, “The Back Page,” and a version of this tabloid outrage exists in the San Diego U-T today. “The Back Page is appalling,” a reader commented just last month. It is still doing its job.

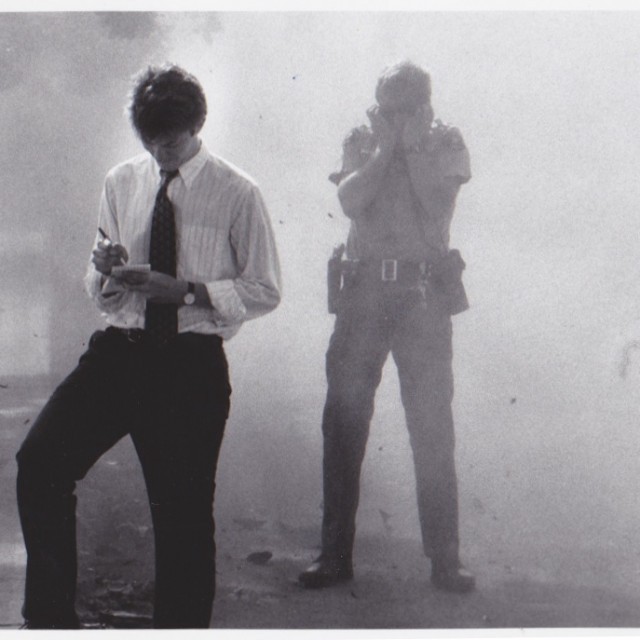

Layne and a sheriff’s deputy at some disaster, San Diego’s North County, circa 1990.

Previously: The Rise and Fall of the L.A. Examiner, a Blog That Was a Newspaper That Never Existed

Ken Layne has held approximately a hundred media jobs around the world. One of the best was writing for The Awl these past six months.