Carmine Infantino, 1925-2013

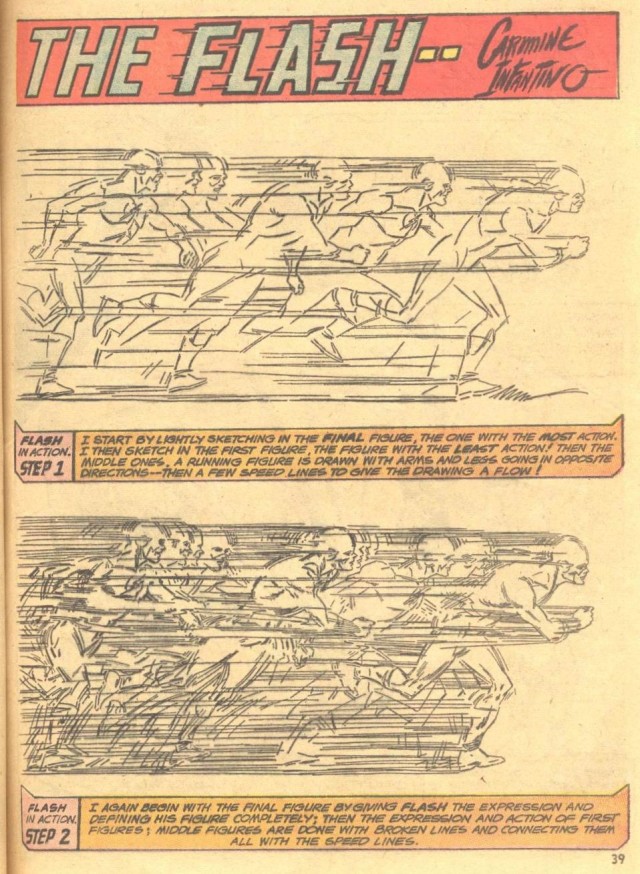

Lifelong comic book man Carmine Infantino died yesterday at the age of 87. If you are even a casual nerd, you know Infantino as that guy that got to draw The Flash off and on for thirty years. And his pencils were immediately identifiable: square-jawed and kinetic, with characters constantly tilting into a run or skidding to a halt. But that’s not all Infantino did.

Born in Brooklyn in 1924, Infantino got into the business while still in school (at what is now the High School of Art and Design), freelancing for “packagers.” (At the time, the early 40s, some comic books were sub-contracted to studios — “packagers” — who would write and draw the stories from scratch and deliver the final work to publishers.) As a hint of his later career, he illustrated the first appearance of DC superheroine Black Canary in Flash Comics #86 in 1947, a character design with Veronica Lake hair that made preadolescents feel funny for decades.

By the mid-1950s, Infantino was full-time with DC Comics. Led by editor Julius Schwartz and along with writers Gardner Fox and John Broome, Infantino was intrinsic to the launch of the so-called Silver Age of DC Comics. The comic book business was contracting, and heat from Congressional hearings instigated by Dr. Fredric Wertham’s lurid (and poorly researched) Seduction of the Innocent, which concerned the immorality being pumped straight into the eyeballs of American children, resulted in the formation of the Comics Code Authority. That self-regulator for the industry prohibited depiction of things like kissing, and crime. This all but erased the super-hero characters that had been so popular only ten years before. With a backlog of Golden Age characters like Green Lantern and Hawkman that were not being used, Schwartz opted to relaunch the characters, the first example of company-wide retconning in the history of comics.

The first character (re)launched was the Flash, and Infantino’s costume design was ground-breaking. This was no circus costume with the underwear on the outside — instead, a sleek red jumpsuit with heavy-soled yellow boots, incorporating the insignias of both the lightning bolt and the wings of Hermes. And the Flash was not muscle-bound, but sleek and lithe, like a marathon runner. The first appearance of the new Flash was Showcase #4, in 1956, and from there DC’s Silver Age began.

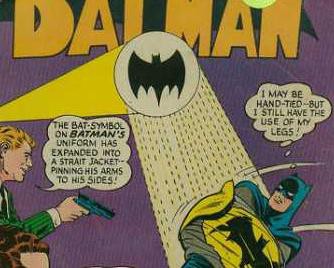

Besides the Flash, Infantino also co-created the Flash’s Rogues Gallery, an assembly of arch-criminals, each usually embodying an element of science (Mirror Master, Captain Cold, the Top), and Batgirl. (No, not Bat-Woman, the one from the 50s, but Barbara Gordon, Commissioner Gordon’s daughter.) But perhaps the most interesting contribution of Carmine Infantino is being indirectly responsible for the Pop Art infusion into comics. In 1964 Infantino was assigned to Batman, who was at the time a bit fusty, as he had spent most of the 50s chasing aliens and fantastical monsters while Robin would stagger around, crippled by separation anxiety. Infantino brought the characters up to date, spiffed up the supporting cast, and — and this is the big one — added the yellow circle to the Bat-insignia on his chest, which before that was just a big grey lumpy bat. Coincidence or not, the uber-camp television series “Batman” that aired from 1966 to 1968 was developed soon thereafter; history made.

Infantino was not just an artist. By the time “Batman” was on the air, he had been promoted to artistic director, making him responsible for the design of all the characters and each cover, and in 1971 he was bumped up to publisher of DC Comics, where he remained for five years. The parting was not so amicable, as is so often the case in the comic book industry, and rumor had it that Infantino never set foot in the DC offices again. But he freelanced steadily, most notably on a sixty-issue run on The Flash in the 1980s, ending with the “death” of Barry Allen, (Flash’s secret identity). Don’t worry, he came back.

Infantino was one of the last surviving architects of the Silver Age of comics. He will be missed by all the little kids who read his comics, back in the day.