Reckoning With 'Thelma & Louise'

Reckoning With ‘Thelma & Louise’

by Maud Newton and Carrie Frye

Carrie Frye: Maud! I rented Thelma & Louise a few weeks ago, and it was, weirdly, only on rewatching that I realized why every so often I get an irresistible urge to rent an aqua convertible, conscript a few female friends for the trip and just drive… south, west, wherever: it’s because of Thelma & Louise! It should have been the obvious source of the daydream, but I had lost track of the full extent to which this movie had hardwired my brain. It’s been 21 years since it came out — it is now old enough to walk into a bar and order a Wild Turkey straight up and a Coke back. I have no memory of when I first saw it — my first distinct memory about it is of listening to two college friends — older, sophisticated (we were all young enough that someone being a year ahead in school made them “older”) — discuss whether they’d be ‘Thelma’ or Louise.’ (There’s a continuum here going back to grade school when you had to call whether you were ‘Kelly,’ ‘Jill’ or ‘Sabrina.’) When I mentioned I was watching it to you, you were able to immediately quote a bunch of favorite lines — which made me think that Thelma & Louise might very well have hardwired your brain, too. If I correctly remember all the concerns swirling around this movie when it came out, that can only mean a dire ending is in store for us both.

Maud Newton: Wait, hold up, Carrie! You didn’t answer the question. Would you have been Thelma, or Louise?

The conclusion to a short series about our strongest movie opinions, past and present.

Carrie: Well, I think that’s partly why I still remember the conversation: listening, I couldn’t decide. I probably leaned Thelma then (a gawky, friendly overpacker, sometimes capable of robbing a store); older me slants more Louise (don’t we all?).

Maud: Obviously I was born Louise. Except that she’s really tidy and I am way too uncoordinated to wait tables. I love how she’s so grimly determined to have fun on this trip that is designed, fundamentally, to make Jimmy miss her.

Carrie: The excellent description of her, from the waitress where they stop for drinks: “The smaller one, the one with the tidy hairdo.” (The same waitress also discloses that Louise had, of course, left her an exorbitant tip.)

Maud: Thinking about your convertible hankerings, I wonder if I started smoking because of this movie. My sister came to visit in the summer of 1993 and for a week we ignored my boyfriend and slept all day and stayed up all night, ordering pizza and watching and rewatching it on video. I remember the two of us lavishing particular delight and rewind attention on the part where Louise narrows her eyes at the guy who’s hitting on Thelma (“what are a coupla kewpie dolls like you doing in a place like this?”) and exhales a big cloud of smoke into his face that makes him wince. “If you don’t mind,” she says, “I’ve got somethin’ I’d like to talk to my friend about in private.” So passive-aggressive and aggressive! I haven’t had a cigarette in almost seven years, and I can’t think of anything that makes me want one as much as that scene does. Luckily, after 13 years of living in New York City, I have learned many other ways of dispersing assholes. I used to be much more Thelma-like in those situations.

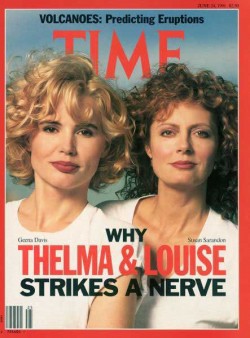

But aren’t all the 90s touches great? Geena Davis’ 80s holdover Guess jeans! Susan Sarandon’s fabulous sunglasses. Jimmy’s Elvis Presleyesque haircut and vest thingie. Brad Pitt’s implicit tutorial on how to wear a chambray shirt (basically, be a young Brad Pitt, hitchhiking).

Carrie: Charlie Sexton as the singer at the local bar!

Maud: Singing John Hiatt!

Carrie: Speaking of 90s touches: In 1991, we were two years past Sinéad O’Connor singing “Mandinka” at the Grammys (are those stonewashed jeans Guess?), and only a year away from her tearing up a picture of the Pope on “SNL.” In a couple years, I’d be having earnest discussions with friends about whether Courtney Love’s nose job (undergone pre-Live Through This) would or would not better enable her to disrupt The System from the Inside, as she’d told Rollerderby was her plan. (We were leery.) I mentioned this movie as hardwiring me; but then it came along at a time when I was so wildly receptive.

Maud: God, so true. When it came out, I was really getting into my Women’s Studies minor. You know, denouncing the patriarchy, feeling guilty for wearing makeup and shaving my legs, advocating the overthrow of language (though Cixous and Irigaray never explained how exactly this would work and I didn’t have any real ideas of my own). Weirdly, it turned out that being furious and resentful about gender inequality didn’t lead to my feeling empowered or energetic or to good decisions of any kind. I spent most of my free time fighting with my boyfriend.

I was instantaneously obsessed with Thelma & Louise. At the time it felt so true and like such a validation of everything I was learning about oppression.

Carrie: Yes! I have an acute memory of going to a packed lecture that Eve K. Sedgwick was giving my junior year and springing out of my seat right before the lecture started and skulking out of the auditorium, because I’d realized my ex-boyfriend was in the row behind me and I couldn’t stand to sit there all night. That was my own conflicted feminist college self right there. I used the word “hegemony” a lot; I wore overalls; but I thought Victoria’s Secret had really pretty bras. But what was even considered feminist — or ‘feminist enough,’ maybe — then was up for grabs and contentious (as it continues to be!).

Maud: Ha! That was such a particular moment. Trying to reconcile my Angry Women anthology — featuring Susie Bright, Lydia Lunch, et al. — with my Shulamith Firestone.

Carrie: Angry Women! (God, I hope that eventually gets re-used as a title of a film about two now-70-something Gen X second-wave feminists in the 2040s: There’d be a scene where, after terrorizing the local merchants and citizenry, they retire to their homes to twist around to Free To Be songs.) So, you know how in the beginning of the movie, Thelma’s not sure what to pack for their fishing trip, and so she brings along everything, including a lantern and the entire contents of her underwear drawer? This movie felt like it had to carry a similar load when it came out. Like it wasn’t enough that it be a sharp buddy road-trip movie in the western mold, but it also had to stand as a definitive statement on feminism and being a woman in the 90s.

That’s a lot of freight for one movie to have to carry, regardless of whether it’s projected out of affection or fear. It’s a pattern that now feels familiar as to what happens when something out of the usual mold about women reaches prominence: the event’s so rare, the movie (or show, or book) is made to carry such enormous amounts of symbolic weight, it can’t help but buckle under the load. It can never just be this wonderful entertainment, this great hero’s story. I don’t think if you really enjoyed the hell out of, say, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid you had to do quite so much hard thinking about whether that meant you were deeply hostile to trains.

You can see the conflict in this 1991 interview with Callie Khouri, who wrote the screenplay (and won a well-deserved Oscar for it). She sounds so exasperated: “People say Thelma and Louise are not role models… Well, they were never intended as role models, for God’s sake.”

Maud: Poor Callie Khouri. She must have been called upon about a million times to answer accusations that the movie was all about gratuitous man-bashing. I can almost conjure up a memory of her being grilled on “Entertainment Tonight.” Maybe I made that up, but you could feel her getting more incredulous and annoyed in each interview. (“Here we are in an age where a guy like Andrew Dice Clay is filling Madison Square Garden and they’re asking me if I’m writing a feminist revenge flick.”) She said her husband described T&L; as “9-to-5 meets Easy Rider,” which is so accurate and underscores the fun of it that a lot of the talking heads missed or were willfully blind to.

Carrie: More Khouri: “It just seems ludicrous in the face of all that’s going on out there to ask whether this is hostile toward men. I don’t think that it is. I think it is hostile toward idiots.” I’m not a misandrist, I’m a misanthrope, you dumbasses.

Something else I’d forgotten about T&L;, and this is a fairly essential part of its DNA, is that Ridley Scott directed it.

Maud: You can really see Ridley Scott’s fingerprints, too: the trucks speeding by, splashing through puddles and careening far too close to the little convertible, the sounds of the road that almost mimic the wail of a far-off siren but turn out to be something completely innocuous, the blue-collar feel of everything and everyone except the FBI guys, and the anonymous old people in anonymous towns dully watching Thelma and Louise through windows.

The direction and cinematography have almost as much to do with the larger-than-life, iconic feel of the movie as the script does. Almost. When you look at this as the 90s film that best satisfies the spirit of the Bechdel Test and also as a sibling of Alien, Ridley Scott starts to look pretty feminist. But it’s not hard to dig up Susan Sarandon’s rejection of that idea: “It wasn’t trying to be a polemic, it wasn’t trying to be anything and (Ridley’s) not a feminist, really, and so it was a turning point for him too. I think it could’ve been a very small movie if a very serious feminist had made it that didn’t put it in this heroic, I mean, that’s what he does, he just put us in this huge heroic kind setting and we took care of the human part.”

Carrie: In this Daily Beast interview Scott gave around the time Prometheus came out, he discusses that he had only wanted to produce T&L;: “I first came on as producer, and I was selling the notion to four or five male directors — this was made over 20 years ago, so there weren’t many female directors to do it — that the movie should be an epic about two women on their journey for freedom. One director who turned me down said, ‘I’ve got a problem with the women,’ and I said, ‘Well you’re meant to, you dope!’” (Strong echoes here to what “Enlightened” creator Mike White said this week about creating projects around women: “If I have a male protagonist, it’s a studio movie, and if it’s a female protagonist, it’s an indie movie.” And even now, there wouldn’t be that many female directors for a producer like Scott to approach.)

This is a movie that ends — spoiler! ha! — with two women sailing off a cliff in a Thunderbird. And yet, Maud, when I went to rewatch it all I felt was exuberance and elation. Khouri’s screenplay has such incredible lines and moments, from the very opening when Louise warns the young girls not to smoke because it’ll ruin their sex drive and then ducks back to smoke herself at the back of the restaurant. Or when Thelma says she doesn’t know how to fish, and Louise says, “Neither do I, Thelma, but Darryl does it. How hard can it be?” (I can hear Sarandon’s and Davis’ particular intonations whenever thinking of any of these lines.) And then once they’re outlaws! “You’ve always been crazy, this is just the first chance you’ve had to express yourself.”

Maud: I don’t think I’ve ever read that interview with Ridley Scott! It’s fascinating that he takes on powerful female protagonists so self-consciously. I wonder why there’s not more discussion of this. I also wonder why I’ve never seen Prometheus.

I completely agree about the exuberance. Thelma and Louise is still so fresh, and the details are so surprising and true, like when Hal tells Darryl that he’s standing in his pizza, or Louise says, “you finally got laid properly, that’s so sweet,” or Thelma keeps putting all the travel-sized bottles of Wild Turkey in front of the cash register and the cashier picks up a pint bottle and says, “Ma’am, are you sure you wouldn’t like the large economy size?” I believe that little imp J.D. really would say, “I like your wife” and then rock his hips at Darryl when they accidentally meet up in the police station. And Jimmy’s such a sweetheart, rushing in with money and declarations of love, but when he starts acting rough in the hotel room, you can feel the history there.

Carrie: Brad showing Thelma how to rob a bank with the blow-dryer as a gun —

Maud: OMG, yes, that’s the best one of all!

Carrie: — “well, I’ve always believed that if done properly, armed robbery doesn’t have to be an unpleasant experience.”

In the second half of the movie Thelma and Louise keep declaring, “I’m awake, I’m awake” and “I’m awake for the first time,” and then… they drive off a cliff. Khouri (and again: apologies to poor Khouri! please tell us what everything in your movie signifies and make sure your answer is meaningful and comforting to our generational experience) has said she sees the ending as not a bummer, but as hopeful, like the car leaps off the cliff and enters into the culture’s group unconsciousness. And even if that quote was borne from interview fatigue and post-narrative neatening, it’s not an inaccurate interpretation of what’s happened: Here we are still gabbing about this movie as something that means a great deal to us, whose two characters, Thelma and Louise, stand as fantastic (if inadvertent) outlaw-adventures and abiding fast friends. But you can’t get around the depressing two-step of: THEY WOKE UP AND THEN… THEY DROVE OFF A CLIFF. Of course, there’s a fine western tradition for an outlaw ending like that. Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (speaking of) go out in a similar glory blaze — albeit without Harvey Keitel running in slow-motion behind them (and more’s the pity: “be carrreeefulllll with those guns, guys”) — but it’s also hard not to see it as a sort of sad blankness as to what options you have “once you’re awake.” (Cf. here, as you reminded me the other day, Kate Chopin’s The Awakening, which ends with the heroine letting “the waters overtake her.”)

Maud: Yeah, there’s not a whole lot of hope here. In a way, that feels right and accurate: we live in a world that was and is in some ways shitty and unfair. Even now a not-insignificant number of politicians seem to doubt that rape exists. And just about everyone knows the feeling of doing one dumb, rash thing in an unjust situation, and watching the situation snowball into more stupidity and unfairness. I like the way Carina Chocano put it: “what ‘Thelma and Louise’ did was unexpected and thrilling. It took all those feelings of alienation and anger … and turned them into something rebellious, transgressive, iconic, punk rock and mainstream. And it forced this feminine perspective onto the popular culture at gunpoint.”

But while I miss many things about second-wave feminism, the movie also underscores its shortcomings: identifying and denouncing misogyny doesn’t in and of itself lead to a way forward, especially if all your energy goes into being locked in a rage-dance with it.

Looking back on that time — and on that movie — I remember feeling that things were shifting, finally and irrevocably. As Chocano says, “For the few years after the release of ‘Thelma and Louise,’ the culture seemed unusually and (in hindsight) unbelievably receptive to the plaintive howls of a generation of girls who, as I did, felt exiled from the culture.”

I often think how disappointed my young self would be to see things like Seth MacFarlane’s stupid “we saw your boobs” song at the Oscars or all those Republican hopefuls opining that women’s bodies know how to stop pregnancies if they’re raped, or to know that, even now, there’s really only allowed to be one admired female director at a time. I didn’t realize at the age of 23, even though history is full of examples of this happening, that in addition to bending toward justice a culture could go backward.

Obviously all of the baggage I brought and still bring to Thelma & Louise is a huge burden to place on a road movie just because it has two women in the lead roles. But, as you say, it doesn’t have much company, so we ponder and scrutinize.

I wonder: what did you think about the scene where they lead the gross trucker off the road and he thinks he’s finally going to get lucky? I used to love it.

Carrie: I was thinking about that while rewatching! It feels shoehorned in and the trucker’s a straight-up cartoon-rodent stereotype, acknowledged… and still, when they shoot up his truck (and they both turn out to be amazing sharpshooters, right?), and it explodes and makes that big, big boom, it gave me a thrill-wave. (When I was rewatching, I was thinking about the burn-down-the-house fires in Rebecca and Jane Eyre… or the flaming gymnasium at the end of Carrie: Like all pent-up female rage ultimately ends narratively in SOMETHING VERY BIG BURNING DOWN.)

Maud: God, exactly! Ridley Scott likes these kinds of sideplots, and sometimes they work beautifully, but this guy, this whole series of events, I dunno. It’s funny and satisfying, in a cheap, ha-ha-that-asshole-got-what-was-coming-to-him way. It’s interesting to see women exacting this kind of revenge. But is it gratuitous? Does it cheapen the film as a whole? Or do I just need to chill out and enjoy the road movie for what it is?

Carrie: The scene where the black cyclist blows pot smoke into the trunk of the cop car has a similar tacked-on, overtly explicit feel now. I’m on board with the agenda, I just don’t think it works.

Maud: Agreed. Even Jimmy Cliff can’t save that one. But for me these hammy scenes don’t detract too much from the overall greatness.

Carrie: Completely. Would you get into that convertible again, even knowing everything? YES. ALWAYS.

Previously: The Future Looks Back On ‘Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story’

Maud Newton is a writer and critic living in Brooklyn. Carrie Frye Tumbls here.