Quit Your Job! Living With the Wild Things, Without Compromise

Wild Nature Institute is the nonprofit creation of wildlife biologist Monica Bond and quantitative ecologist Derek Lee. They live and work for much of the year in Africa, where they study and inventory iconic and threatened wildlife populations such as the Masai Giraffe, which is rapidly declining due to lost habitat, disease and illegal hunting.

Ken Layne: Hello, Derek Lee! Because you are traveling between Nairobi and Zanzibar and I’m on the other side of the planet, maybe we’ll do this in email format? So what is it that you and Monica do in Africa? This past week sounds like it held a lot of safari travel and adventure.

Derek Lee: We are extremely fortunate to live and work in Tanzania, which undeniably has the best wildlife experience on Earth. Nowhere matches the incredible diversity combined with the extremely high density of mammals and birds found in northwest Tanzania. And there’s still the full suite of predators and scavengers indicating a relatively intact food web. The area also holds some of the last remnants of our planet’s pleistocene megafauna — elephant, rhino and giraffe. But it isn’t as glamorous and exciting as the typical romantic stereotypes of safari.

Safari just means “travel” in Swahili, and travel doesn’t always go smoothly, particularly when you are driving remote dirt tracks in Africa in a 20-year-old Land Cruiser and camping rough in the Bush. Our typical workday of surveying starts before dawn so we can eat and break camp to start surveying at first light. Animals are more active early in the day, so we have to be ready by 6:30 a.m. Then we spend the next 12 hours bouncing over what we euphemistically refer to as “roads” but are often just vague tracks across the savanna through washed-out areas, swamps, or places where the road has otherwise disappeared.

We look for ungulates — animals with hooves — and when we find some we count and record their distance from us, using a laser rangefinder; that’s so we can use statistics to correct our counts because as you can imagine animals are less likely to be seen when they are far from the “road.” When we see giraffes, we drive off-road to get close enough for a good picture of their right side. Photos of the giraffes’ unique fur markings go through pattern recognition software to identify individuals and track their births, deaths and movements. This is where we usually get stuck. It can be mud or sand or a huge hole dug by elephants or aardvarks, but eventually while off-loading we get stuck, and then have to spend hours getting unstuck. There are no tow trucks in Tanzania and you can wait days or weeks before any other vehicles or tractors come by, so we have to be prepared to rescue ourselves.

After 12 hours of rough driving and surveying and getting ourselves unstuck, we find a relatively flat place that doesn’t look too elephant-y or lion-y and we pitch tents, cook and eat dinner, and pass out. That’s every day for about a month, three times a year, to monitor the ungulates in each season. Between surveys we live in a small cottage in Arusha, tumbling numbers, writing reports and scientific papers, and raising money.

Ken: You’ve been traveling pretty much since I met you 20 years ago, and it seems like you used to work for a while in the United States to make money, and then disappear to Belize or the Sahara or some other exotic destination until you were broke again. Now you’re doing your life’s work while living in the wildlife nirvana of Earth. How did you pull that off?

Derek: That’s a pretty accurate description of my strategy. I spend a period of time earning money, then spend time doing what I want. I can usually earn enough in a few months working in the U.S.A. to live the rest of the year as I please. The key is to never accept any debt and to live within a budget.

I consider the colossal good fortune of being born in a wealthy country to be almost an obligation to use that enormous advantage for the good of the planet. There is perhaps nothing more tragic to me than the wasted potential of a human being who, given the education and material resources of a rich country, decides to dedicate his or her life to servicing a mortgage or other debt by working in some soulless, non-life affirming occupation. Some may claim they are waiting for retirement to pursue their dreams but we all know “what happens to a dream deferred,” it withers “like a raisin in the sun.”

I chose episodic retirement where I pursue my dreams at many different ages and life stages. A more prescient and organized mind could know what they want from life and work to build the wealth and expertise needed to accomplish their goals over a lifelong plan, but I lack those qualities. I’ve got a more circuitous and tangential mind, so I’ve pursued different dreams at different life stages. But I think the main current of my efforts and endeavors has been curiosity about this amazing planet’s life forms and ecological systems combined with the desire to make life better for all of us — better for humans, better for animals, better for plants, better for all life. I also feel existence contains sufficient uncertainty that time should be considered precious and opportunities seized, especially when youthful vigor is a once in a lifetime gift.

I have met retirees all over the world and they all get wistful when I explain how I am seeing the world and working for good and they all say, “That’s great! I wish I had done that.” People from the U.S.A. have every advantage in life, they were born in one of the wealthiest nations, speak the global language of English, can go to most any other country easily, and get excellent free education through secondary school followed by opportunities for low-cost higher education through public universities. Consider how different your life would be if you were born a rural peasant rice farmer. (I’ve heard this is the most common human situation, so it’s statistically much more likely than being born in America.) Consider how different your life could have been if the dice rolled differently and you came into existence outside the U.S.A.

Ken: For a long time you were spending half the year on the Farallon Islands with the elephant seals, and from looking around the Internet I learned that you had become one of the world’s leading experts on elephant seals. What was it like on those rocky little islands, and when/how did Monica join you on Los Farrallones?

Derek: The Farallon Islands are magnificent. Again it was the intense diversity and superabundance of wildlife that was so cool. Hundreds of thousands of seabirds of 13 species, and thousands of marine mammals including five species of pinniped and lots of dolphins, porpoises and whales, plus the amazing rocky intertidal organisms and the salamanders, and of course the white sharks.

I had some glorious years out there, but how I got there was a bit of serendipity. Like I was saying, I didn’t have a grand perfect plan worked out from the start, so in my youth I was more driven by curiosity and thirst for knowledge. I was doing any good-paying job to finance my travels and studies. But I wanted a way to finance my personal dreams that would be enjoyable itself.

When kids ask me how to get a job like Farallon Islands biologist, I tell them to study statistics, diesel engine mechanics, and small-boat handling. Anyone can count animals but you’ve got to have a little value-added practical skill to get the sweet gigs.

I grew up camping and love wildlife, so I looked into jobs in wildlife conservation, and most required a college degree in that field. Luckily for me, Humboldt State University in California offers a respected wildlife management degree, and as a public school was very affordable. I had a chunk of cash saved from temp office work, nights parking cars, and weekend boat charter duties. So I went back to school. While there, I discovered I had an aptitude for math and statistics I never knew about. I became an expert in a niche statistical field of demography and population biology. That got me a job tumbling numbers at the Point Reyes bird observatory, where I analyzed long-term data for a seabird conservation plan.

A year later, the guy who collected elephant seal data on the Farallon Islands retired. I knew about diesel engines and boats and solar-power systems and plumbing from my diverse experiences up to that point, so I had the practical skills that were necessary. The Farallones are remote granite rocks, 30 miles offshore from San Francisco, so we’re pretty much on our own out there. I guess my self-sufficiency and proactive problem solving worked well out there. I like to envision how a situation can go terribly wrong in the worst possible manner, so I’m ready for every eventuality. That way when the power goes out and I’m trapped offshore in a small boat in rough seas, I have a plan.

When kids ask me how to get a job like Farallon Islands biologist, I tell them to study statistics, diesel engine mechanics, and small-boat handling. Anyone can count animals but you’ve got to have a little value-added practical skill to get the sweet gigs.

Monica, my beautiful and talented wife, joined me for most of my island time. She’s also a highly trained and experienced biologist, so she made the work go very smoothly. She has a gift for remembering numbers, too, so she kept close track of the tagged seals and their pups. During our time on the Farallones, we did some groundbreaking work on elephant seals, seabirds, and arboreal salamanders. I would love to go back if I got an opportunity.

Ken: Something terrible happened with her finger at some point, right?

Derek: Yeah, Monica got a couple arcane diseases out there. One was “seal finger,” which is something known from sealers a hundred years ago and it’s super painful… to the point that sealers were known to cut off their own fingers to stop the pain. She was up all night pacing around the kitchen table, just as the sealers paced around their boats. That helped us diagnose it. All the resident physicians at UCSF were keen to see her finger with its rare disease, and the doctor even published a picture of her finger in The Lancet, as the only known photo of seal finger. She also got Erysipeloid of Rosenbach or some such thing — I think that one is called “fish-handlers disease.” It caused burning and swelling. She’s all cured from those now.

But here in Africa, she’s got some weird neurotoxin thing from a bug bite that makes her feel like she’s choking. She isn’t really really choking, her airway is fine, but she feels like she’s choking. Also her lips and left arm tingle all the time. It’s very strange.

Ken: Jesus! And you both look so healthy and happy in the Wild Nature Institute videos. What are some other life-and-limb dangers to this kind of work, whether on an island or in Africa today?

Derek: Risks to life and limb are a lot more common in this line of work than a desk job, sure. Mortality is something that’s much more of an everyday encounter here in Tanzania. It seems almost every couple weeks we hear of a friend or associate who has died, or someone close to them has died. Health care is almost nonexistent here, so disease and accidents claim a lot of people that perhaps could have survived given the proper medicine or treatments. As always, car accidents are the biggest threat. It’s like the old California surfers response to people who ask, “Aren’t you afraid of great white sharks?” The answer is, “The most dangerous part of surfing is the drive to the beach.” I’ve snorkeled at the Farallons and elsewhere in the Red Triangle, but I’ve always been aware of the shark potential and just stick close to cover and don’t bob at the surface looking like a seal. I also don’t swim with actual seals or sea lions because then you’re just asking for it — you will definitely be the slowest of the bunch.

They have a saying here in Africa about lion attacks: “You don’t have to run faster than the lion, just faster than one other person.”

That reminds me of another bit of advice: Don’t turn your back on the ocean. One day on the Farallones, one of the research assistants saw something weird in the water. It turned out it was a human body, looked like a fisherman, floating outside Sea Lion Cove. We called it in to the Coast Guard and kept an eye on him, but eventually it got too dark to see him any more. We called him Bob because that’s all he did, and it was nicer than referring to “the dead body.” He was probably some poor guy who got washed off the rocks while shore fishing.

Word to the wise: If you see a body don’t report it as dead, because that drastically slows response times. Leave the diagnosis to the experts and report “guy in the water,” so the person’s loved ones will have some closure.

Here in Africa they say mosquitoes are the deadliest animal, but amoebas in the drinking water are also big killers, especially of kids. But I’m sure everyone wants a lion story, so here’s mine:

One morning while surveying in Tarangire National Park, we were breaking camp while boiling water for tea. Our assistant Gasto quietly said, “Derek, come look at this, look over there,” and pointed to a lioness about 30 meters away.

Then Gasto says, “That was the first one I saw, then I saw that one,” and he pointed 20 meters away. “Then that one,” just 10 meters away. “Then that one, and that one ….”

They were all just sitting and looking at us. We quickly and quietly packed up and got in the car. There were 13 lions altogether, lying all around our camp, but they were all gorged with the zebra they’d killed behind our tent in the night. It was unnerving, but I didn’t feel too threatened.

Ken: Tell me about the people of Wild Nature Institute. Is it really just you and Monica, or do you have staff or contractors or volunteers?

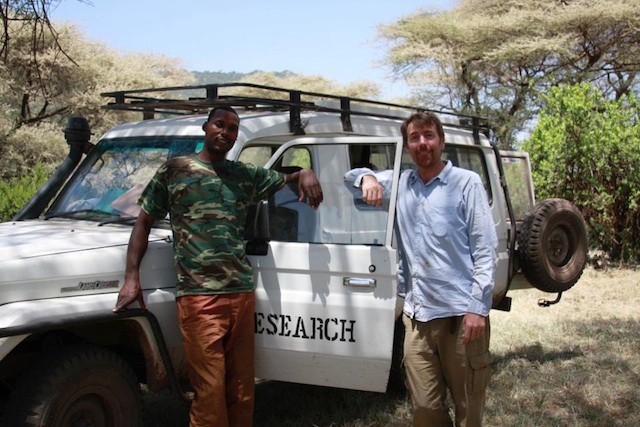

Derek: The Wild Nature Institute is just me and Monica as core staff. We hire a Tanzanian field assistant and driver. Gasto is Wa-Arusha, so he can communicate with the Masai people in our study area who don’t always speak Swahili.

We used to have a Tanzanian partner, but he was murdered last June trying to stop a lunatic from burning a neighbor’s house. That was a real tragedy, because Robert was one of the few Tanzanians I’ve met who really loved and valued the wildlife for their intrinsic worth and didn’t just see them as a resource to be exploited. He was working on our public-education campaign to protect the last migratory corridor in Tarangire. This area used to have a huge wildebeest and zebra migration that was second only to the Serengeti, but habitat loss and poaching has decimated the populations and only one route remains. Robert was organizing Masai communities in the corridor to make land-use plans and preserve the habitat for wildlife. Now that work is stalled until we can find a new ambassador to the communities.

Robert and Derek doing field research.

Ken: And that’s crucial, because without community involvement you’re stuck with “paper parks” that don’t really protect species or habitat, or parks as islands cut off from migration corridors. But despite all this death and disease and losing momentum when you lose somebody like Robert, or maybe because of these kinds of tragedies that do make you much more aware of being alive, a lot of people reading this are going to be thinking, “How can I do this? How do I ditch my job and go to Africa to work on wildlife habitat and follow giraffes around?” So how does someone go about doing this?

And because most people aren’t going to do conservation biology in Africa, how can they take part in the very noble and necessary work of preserving these species and habitats? Is there a way to do eco-safari tourism that’s actually helpful, or is it best to focus on your own species in your own hometown or closest wilderness, or should people just click the Donate button and give to the cause while reducing their taxable income?

Derek: Our work would probably seem difficult and tedious to most people. We’ve had a few join us on these exclusive private safaris where we give them a taste of what wildlife biology is like, but done in luxury. The game-viewing drives are more relaxed and we take them to only the best places with lots of great animals. We also give them a more plush camping experience or put them up in nice safari lodges. They get a private safari with personalized guiding from expert scientists working in the field (us), and all the revenue goes towards our research expenses. That’s one way to support our work and get an awesome and unforgettable experience.

And I’d love it if everyone spent at least part of their days fighting to protect whatever natural habitat remains near their home.

Wild Nature Institute speaking to the Biology classes at St. Constantine’s International School about ungulate research in Tarangire National Park.

Ken: Where does climate change specifically hit the kind of species and habitats you’re working with now? And what is being done on a regional/continental level to deal with weather and coastal changes?

Derek: Most folks are probably overwhelmed by global warming and climate change, but the biggest threat to our planetary ecosystems — which are the life-support systems for us, too — is habitat loss through development. The human footprint has grown all out of proportion in the last 50 years.

We desperately need to protect all the remaining vestiges of wild nature that are still here. We do not need more housing subdivisions or shopping malls. There are plenty of them already, and infill redevelopment of existing human-dominated lands can provide for all our growth. Once habitats are destroyed or degraded, they never come back as they were. We must keep them intact. As Nobel laureate Wangari Maathai said, “We didn’t create his planet, we have no idea how it works, so what right do we have to change it so completely?”

I don’t see those things changing anytime soon, so all we can do is protect as much nature as possible and hope there is enough resilience designed into our planets biological systems during their millions of years of evolution to keep us alive through the coming changes.

We’ve got to be careful stewards of the remaining natural places and not let the forces of development and exploitation ruin this planet with their greed. Climate change is here and there’s nothing we can do about it except to stop burning fossil fuels and stop keeping billions of livestock. I don’t see those things changing anytime soon, so all we can do is protect as much nature as possible and hope there is enough resilience designed into our planets biological systems during their millions of years of evolution to keep us alive through the coming changes. And don’t buy property in a floodplain.

Ken: What’s the greatest wildlife encounter you’ve had in Africa, and what’s the best one overall?

Derek: I’ve seen so many crazy things in my life: orcas toying with a bird, elephant seal bulls battling to the death, lions killing impala, grey whales exhaling in my face, a million shearwaters feeding over humpbacks, a million wildebeest migrating after the rains, dolphins making phosphorescent trails around our boat during a midnight sail, but I still wake up every day expectant of what new wonder the world is going to surprise me with. It’s a great life!

Ken: Do you remember that whale, maybe a Beluga, that surfaced alongside our boat when we were hungover and fishing off the bay of San Quintin down in Baja? That is still one of the most insanely vivid encounters I’ve ever had, something about the morning light and the blue water and that shiny black whale at face level giving us a good shower. It’s similar when I come across a bobcat or even some mule deer standing in a cluster of Joshua trees by my house, or when I see mountain lion tracks in a sandy wash when I’m hiking alone and it’s almost dark. Does it ever get mundane to be in close contact with these wild beasts, or is it always kind of magical?

Derek: I remember that fishing trip, was it a Beluga? Maybe a Grampus (rissos dolphin) that far south. Either way, I have to say the wonder and magic of seeing the glory of the natural world continues to astound me. On the Farallones we had the saying “every day is Tuesday,” because the work schedule was very repetitive and we worked every day and the repetition is a big part of our Africa work also. But at the same time every day is punctuated by several spectacles of nature that deserve to be a featured nature documentary with David Attenborough giving breathy commentary.

Ken: You are right about that whale on the Bahia Santa Maria. I had looked it up a long time ago, because it was such a tremendous sight and I’d never seen that kind of whale off the West Coast. I called it a pilot whale in something I wrote about that trip, and I see the pilot whale is also called the Grampus. That is some good animal memory, Derek.

Can you describe a night on the savanna or wherever you’ve recently been out camping, as far as the sounds and moods and bugs and just how you might end the day, whether around a fire or drunk on your laptop in a tent or whatever actually happens?

Derek: We had a great evening last month during a wildebeest count, helping our colleague Tom Morrison. Watched a spectacular sunset over the Rift Valley Wall and the sky was all purply-pink over the flamingo-filled lake, so there was so much color it almost hurt to look. We made camp under some huge Acacia tortilis trees and they were blooming, so they were like giant flowery umbrellas made of billions of tiny puffball flowers that were filling the air with their perfume. There was a buzzing in the air because so many flies and bees were gorging on the nectar flow in the Acacias, but they didn’t bother us.

Right at sunset, the tsetse flies get aggressive looking for a final blood meal, so that’s annoying. But once it’s dark they go to sleep and there’s peace. You hear constant bird calls, especially from the doves and spurfowl. And there will usually be some falcons or other raptors hunting in the dusk. We watched the full moon rise over the Rift and sipped our sundowners of passion juice and brandy we call a Manyara Kiss. Then we talk about whatever ridiculous new wildlife encounter we had that day, such as the bat-eared fox play-fighting with some mongooses, or a baby elephant reaching its trunk into the car to sniff us, or a serval cat hunting along the edge of a marsh. We chop up a bunch of fresh vegetables and eat a hearty stew, then lie in our tents listening for hyena squeaks or lion roars until sleep overtakes us.

Ken: What’s the ultimate goal of Wild Nature Institute, both for you and for the institute. Are you going to be out collecting lion poop when you’re 80 years old, four decades from now? I can’t really see you sitting in an office in Washington or London.

Derek: Our goal is to continue our work of researching wildlife and their habitats and doing education and advocacy to protect the last wild places on earth. I do so hope I’ll be collecting lion loop when I’m 80 because that will mean there are still wild lions! I’ll never retire because I love my life and can’t imagine I’ll ever satisfy my curiosity about the world. One thing I would love is if I could quit fundraising and focus all my concentration on the work itself.

Ken: You and every other conservation person. At least you’ve got fiscal sponsorship so you’re not sweating over weekly 501(c)3 reports in a tent, I hope! Say hello to Monica, and thanks so much for doing this, and send us off with some inspiration or something!

Derek: To anyone dreaming of a more passionate and meaningful life, I say do it! Eliminate your debt. Live more simply. Chase your dreams. Die with no regrets over what you didn’t try.

The Wild Nature Institute partners with the Fund for Wild Nature, which has been funding grassroots conservations work for 30 years. All photos and videos courtesy of Wild Nature Institute.