John Adams, The Lovable Schlub In White Tights

John Adams, The Lovable Schlub In White Tights

by Sarah Marshall and Amelia Laing

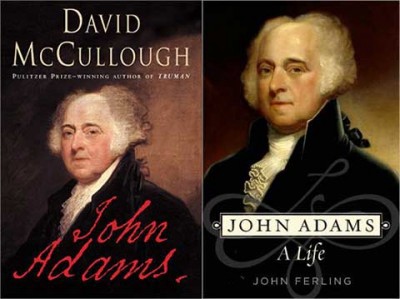

Sarah Marshall and Amelia Laing are reading their way through biographies of all the presidents, in order. This time up, it’s John Adams and the books discussed are David McCullough’s John Adams

and John Ferling’s John Adams: A Life.

Sarah Marshall: In the first installment of this series, Amelia and I talked about George Washington, and we both came to the conclusion that, despite the insights a biographer can afford us, it’s still hard to see him as a man rather than a symbol. No matter how many self-questioning diary entries we read, we can’t quite forget the image of the giant in buff and blue. Not so, however, with John Adams. From the very first — especially in David McCullough’s meticulously and lovingly detailed biography titled simply John Adams — Adams comes across as unavoidably human.

Even more amazing than this is the fact that, after reading McCullough’s book, I could almost (almost! mostly!) believe in the Adams I saw in the 2008 miniseries adapted from it, in which Adams himself was played by Paul Giamatti, the King of Schlub. Previously, this seemed to me to be odd almost to the point of anachronism: weren’t the Founding Fathers meant to be played by the dashing, the high-cheekboned, the classically trained and vaguely British? In the case of Washington (whom I can’t help picturing as Liam Neeson), yes. In the case of Adams, no. In his humanity — his anxiety, his pride and ambition, and his anxiety about his pride and ambition — we can recognize ourselves, and learn that greatness and schlubbiness can live side by side. (Trust me that McCullough says it more articulately.)

Amelia Laing: I haven’t seen the miniseries, but after reading John Ferling’s John Adams: A Life — I can see how Paul Giamatti would be well cast in the role of the second American president. Giamatti is no Brad Pitt, and John Adams was certainly no Washington. But both are easy to love once you get to know them.

Sarah: There’s also the fact that, after spending eight hours watching the miniseries, or reading 650 pages of McCullough’s book, you have no choice but to love either protagonist — it’s a kind of historical Stockholm Syndrome, almost. But a good kind.

Amelia: And one that Adams might have been happy with, as the blustery Adams that emerges from Ferling’s biography screams to posterity, “LOVE ME!” Both Washington and Adams were concerned with how historians would view them. Washington showed his concern through action: he took painstaking measures to preserve his papers. Adams, on the other hand, seemed to write his diary entries without thinking that someday people would read them; they’re peppered with tortured navel-gazing passages wherein he details his yearning to achieve “Honour or Reputation,” to be “a great Man.” In his early twenties, he told a friend that he wanted to avoid the fate of “the common Herd of Mankind, who are to be born, and eat and sleep and die, and be forgotten.”

Sarah: Adams’ early diary entries and neurotic meditations on the place he would occupy in the world were what first endeared him to me — by expressing his anxieties, he was also showing that he was hyperaware of them, and of the rest of his flaws. Compare that to the heroic persona Washington quite consciously projected, and you immediately have the impression of a more human figure. It was also an image that corresponded to the specific role Adams played within the Revolution: Washington, as the leader of a disobedient and poorly trained army, needed to project authority and control. Adams’ skills were in rhetoric, oratory, and analysis. In another life, he may have been an academic instead of a politician, but as it was he used the formidable abilities he had in direct service of his nascent country. That he worked largely behind the scenes, and in the less glamorous positions of the Revolution — a writer, not a rider — may explain how sadly overshadowed he’s been by his contemporaries.

Amelia: When Adams arrived in France in 1778, many mistook him for his cousin, Sam Adams, “le fameux Adams.” When he corrected them, he was treated as “a Man of no Consequence.” This anecdote is but one in a series that illustrates how the good-intentioned Adams was often confronted with an indifferent, even disappointed audience.

Sarah: And for all his neurosis and perpetual irritability (Abigail Adams singled out the latter as her husband’s only flaw), Adams was remarkably good-natured, even as his Presidency dissolved into a morass of libel, with his detractors — both Federalist and Republican — ruthlessly smearing him as a grasping, power-hungry monarchist irreparably corrupted by his time in England.

Amelia: Adams is like that guy friend you have who constantly blames his involuntary celibacy on the fact that girls don’t like him because he’s “too nice.” You know the type. The guy who texts you when he says he will, the guy that buys flowers “just because.” The guy who tries to play by the rules but, much to his bewilderment, never actually seems to get any.

Adams is like that guy friend you have who constantly blames his involuntary celibacy on the fact that girls don’t like him because he’s “too nice.”

Adams is totally that guy: despite his intense work ethic and his commitment to the promotion of “the happiness of [his] fellow men,” several historians have maintained that our first vice president and second president never attained the greatness he so desperately sought.

Adams must have realized that he would never supplant, nor indeed would he ever even compete, with other Founding Fathers in history books. In a letter to his friend Benjamin Rush, Adams wrote, “The history of our revolution will be one continued lie from one end to the other. The essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his rod — and henceforth these two conducted all the policy, negotiations, legislatures, and war.”

Boohoo, Adams. Calm the fuck down. You’re still beloved, if only by a select few.

Adams shouldn’t have been so hard on himself. No, he wasn’t as sexy as George Washington, or as charming as Benjamin Franklin. But Adams has been called “the Atlas of Independence” because he managed to keep the new nation together. He avoided war with France during his one-term presidency, no mean feat considering the bitter fighting between the pro-French Republicans and the anti-French Federalists. He kept his wits about him during and after the XYZ Affair, a pretty impressive achievement, as many in and out of politics were crying for blood.

Sarah: Last time around, we explored Washington (the man, the myth, the legend, the gross false teeth), and came to the conclusion that much of his greatness sprung from self-doubt and a mile-wide conservative streak. To wit, many of Washington’s decisive victories in the Revolutionary War came from timely retreats, which seemed to him then expressions of abject failure. From him we learned that leading a revolution isn’t about being a swashbuckling hero, but has a lot to do with being a keen judge of character — of individuals, of nations, and of yourself. Adams’ single-term presidency may pale in comparison to Washington’s and Jefferson’s, and we may take it as evidence of his mediocrity that his primary victory came in avoiding going to war — but what greater victory can a president really claim, especially when the surest route to national unity (and his own popularity) seems to lie in bloody conflict?

Perhaps chief among Adams’ attributes as a statesman was his ability to see people and situations for what they were. His keen understanding of man’s inherently flawed nature directly informed his conception of what a democracy should look like, and his endorsement of a system of checks and balances. When other Americans — especially Jefferson — saw the French Revolution as a laudable declaration of man’s rights, Adams recognized it as representative of an ideology that would inevitably lead to senseless butchery. Following the Boston Massacre, Adams first used the incident to ignite the revolutionary spirit in the hearts of Americans, then defended the British soldiers in court when he learned that no other lawyer would take their case. He won.

Amelia: When Adams won his first trial in the fall of 1760, he wrote euphorically, “The story of Yesterday’s Tryal spreads. They say I was saucy.” In an article Adams wrote under the pseudonym Humphrey Ploughjogger, he implied that those who opposed the Stamp Act were also protesting the decadent vices of modern Europe. This early opposition to what he viewed as the sullying influences of a degenerate civilization represents how he envisioned the future of the new nation: Ferling writes that “while others looked toward an American vista that included democracy, the unencumbered supremacy of legislatures, and manhood suffrage, Adams sought the preservation of much of the old order, minus any British influence.”

The Adams that Ferling depicts was unimaginative. While Washington was ever forward thinking, constantly evoking the “millions unborn” Americans, Adams wanted to return a purer, unsullied Puritan New England past. He saw the United States’ removal from the British Empire as a step towards what he imagined were the better social mores of an era long gone. He was understandably horrified by the French Revolution, but failed to fully comprehend the positive implications of the upheaval.

Sarah: To discuss the differences between McCullough’s and Ferling’s takes on Adams, I have to descend into a theatrical anecdote, which goes as follows:

Once, during my time at Unconscionably Expensive Private Liberal Arts College (or UPLAC), I appeared in a play about Hume. They play had about thirty Enlightenment characters, and though I had wanted to play Boswell, I was cast in the role of several servant girls and prostitutes, and Louis XV. Since the play was about four hours long, we decided to produce it as a stage reading, and all wore vaguely historical white peasant blouses and petticoats. We had also decided that, since the play was about language and philosophy, we would toss the script’s pages onto the floor as we finished reading them, and to walk around without getting stuck the paper, we coated our feet with talcum powder before the play started. It was a long, stuffy, powdery night.

When she spoke about him, she grew fidgety and flushed; when she mentioned how much she loved his intelligence, but more than that his integrity, she spoke more quietly, as if Hume was down the hall buying a Sprite from the vending machine and she didn’t want him to hear her gushing about him.

I think of this play in relation to Adams partly because it took place during as similar time period and involved some of the same people (though Louis XV was long dead by the time Adams reached Paris, and Adams was instead far more charmed than we would perhaps like to believe by Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, calling her “an object too sublime and beautiful for my dull pen to describe”). Mainly, though, reading John Adams reminded me of the playwright herself, who was a writer-in-residence at UPLAC at the time, and whose name I have long since forgotten. When she came to watch us during rehearsals, she confessed that, while writing the play, she had fallen in love with Hume herself, to the extent that anyone can fall in love with a long-dead Scottish philosopher. When she spoke about him, she grew fidgety and flushed; when she mentioned how much she loved his intelligence, but more than that his integrity, she spoke more quietly, as if Hume was down the hall buying a Sprite from the vending machine and she didn’t want him to hear her gushing about him. Talking to her that day, I felt slightly baffled but mostly envious: I wanted to care about anything outside my own petty anxieties that much, to not just know abstractly why a historical figure was important, but to have so vivid an understanding of them that I felt as though we had met.

While at UPLAC, I read mostly sad poetry, some of which I almost understood. Now, I read mostly historical biographies, and the most important thing I understand about them may be this: you can’t write a great biography unless you fall in love with your subject. No weaker emotion can sustain you through the thousands of hours of archival work, writing, editing, returning to the archives, fighting for the right to get into the archives, and more writing that any great — or even good — biography requires. Read Nancy Mitford on Madame de Pompadour and you see a woman in love with her subject, uncovering not a foreign queen but a kind of mother or sister figure (and going so far as to throw in bitchy comments about her subject’s rivals); read Nancy Milford on Zelda Fitzgerald, Amanda Foreman on Georgiana Cavendish, or Antonia Fraser on Marie Antoinette, and you’ll see the same thing. Robert F. Caro’s planned five-volume biography of Lyndon Johnson is now four volumes and over 2,500 pages long; by the time the final volume is published, Caro will have been working on the project for over a quarter of a century, and will perhaps have given more thought and care to Johnson’s life than Johnson himself ever did.

Looking for great biographies, I learned to avoid those authors who had cranked out books on ten or twenty historical figures, as if trying to become experts not on individuals but on entire centuries. (Antonia Fraser is the exception, as she has been publishing for six decades and was romantically involved with Harold Pinter during four of them. The woman can do anything she wants.) A great love takes time to develop, and a biographer must, ultimately, learn to love all of their subject, because only then can they bring their subject fully to life, and deliver to the reader a fully recognizable human being.

McCullough has clearly done just that with Adams. McCullough loves Adams, and he will make you love him, too — as I do now, having fallen under McCullough’s spell. His biography is the result of tens of thousands of pages of reading, and years of work. McCullough, as a man of letters, clearly appreciates his kinship with Adams in that respect (Adams was a rapacious reader and kept up a voluminous correspondence throughout his life), as he does Adams’ abilities as a writer. As a young schoolteacher, Adams was already exercising his keen powers of observation (and his equally keen wit), writing:

I sometimes, in my sprightly moments, consider myself, in my great chair at school, as some dictator at the head of a commonwealth. In this little state I can discover all the great geniuses, all the surprising actions and revolutions of the great world in miniature. I have several renowned generals but three feet high, and several deep-projecting politicians in petticoats. I have others catching and dissecting flies, accumulating remarkable pebbles, cockleshells, etc., with as ardent curiosity as any virtuoso in the Royal Society… At one table sits Mr. Insipid foppling and fluttering, spinning his fingers as gaily and wittily as any Frenchified coxcomb brandishes his cane and rattles his snuff box. At another sits the polemical divine, plodding and wrangling in his mind about Adam’s fall in which we sinned, all as his primer has it.

Throughout his life, Adams would never really move beyond the role of small-town schoolteacher: surrounded by squalling, self-interested personalities, it was always his job to find reason in the midst of chaos, and a humble job it was on many occasions. Yet it was his prodigious ability not as a soldier or a president, but as a reader&mdahs;of people, of governments, and of history — that allowed him to provide the voice of reason for both the American Revolution, and the even more formidable business of running an infant country. It may partially be my Stockholm Syndrome talking, but even if you’re not as enamored of Adams as I was, McCullough’s book will convince you that we need more people like Adams in America today.

Read David McCullough’s John Adams if: You want to fall in love with John Adams (and feel a little better about your own neuroses).

Read John Ferling’s John Adams: A Life if: You want to take Adams with a grain of salt, and laugh at Adams more than you laugh with him.

Next up in series: Joseph J. Ellis’ American Sphinx: The Character of Thomas Jefferson (Sarah) and Fawn Brodie’s Thomas Jefferson: An Intimate History (Amelia).

Previously: Huzzah, George Washington, Secret Basketcase And First President

Sarah Marshall and Amelia Laing mean no offense to the wonderful and irreplaceable Paul Giamatti.