How To Get Your Readers To Write Your Newspaper For You

How To Get Your Readers To Write Your Newspaper For You

An old schoolhouse, two feed stores, an “84 Lumber” yard, the sheriff’s substation and a western wear store were the notable tenants on the main street of Lakeside, California. It was just a half-hour’s drive from the beaches of San Diego, but it had the dusty half-abandoned look of a Texas panhandle town. The “lake” was a pond in the small park at the end of the road. State Highway 67 ran parallel to the two-block-long downtown, and in a faded Old West-themed plywood strip mall, a lean middle-aged man in a brown corduroy sports coat was behind his desk with his typewriter and a coffee mug full of Bushmill’s, telling stories of local corruption and ineptitude.

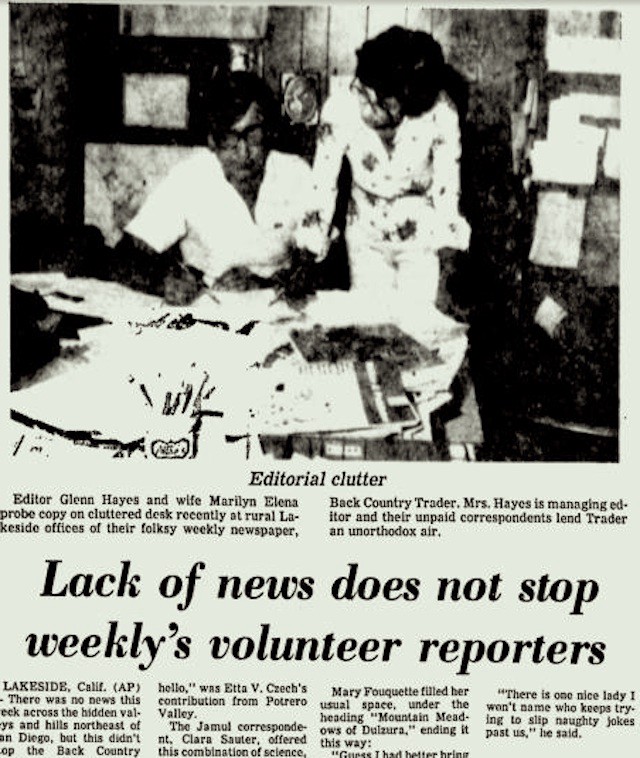

He stopped to cough for a few minutes, and I used this pause in the monologue to ask if his column was done. The typesetter and paste-up person was long gone for the day. When dawn broke in a few hours, the pages would need to be ready for the printer. Glenn Hayes still had some talking to do, before he finally finished his tale and pecked out a few paragraphs of copy that would run on the inside front page. It was rarely anything worth the wait, but it was part of the ritual of publishing the Back Country Trader.

I didn’t even work there. My girlfriend did, and it was her first journalism job. We lived in the “back country” of east San Diego County, another half-hour up the piney mountains from Lakeside, and I got into the habit of hanging around on deadline night. I knew the basics of typing articles and captions and ad copy into the Linotype machine, and I could make half-tones of photographs and paste up the pages. Glenn was used to having people work for nothing but the joy of being in a newsroom, so I did whatever was necessary.

Glenn’s command center was a partially enclosed office at the back of the long, filthy space that functioned as advertising department, production department and newsroom. It had fake wood paneling and a vast collection of books, reports, gewgaws and gag gifts on its second-hand bookshelves. Cigarette smoke hung beneath the industrial fluorescent light fixtures, and the whole place stank of old newsprint and ashtrays.

“My wife got me in to meet Jimmy Carter when he was visiting El Cajon,” said Glenn, who had been married a few times here and there. “I was at the end of the receiving line and everybody’s saying, ‘What an honor!’ or ‘This is such a pleasure!’ and Carter gets up to me and I shake his hand and won’t let go and say, ‘Mister President, what will you do to address the problems we have in the back country?”

“Did you get an answer,” I asked, “or get arrested?”

“Oh, he said some horseshit about being a farmer and understanding the concerns of the rural poor. I’m sure he forgot about it by the time he was on his jet again.”

The paper served an immense area, from the apple orchards of Julian to the ocotillo sand flats along the Mexican border. Lakeside was a metropolis compared to most of these dots on the map: Jacumba, Alpine, Campo, Santa Ysabel, Guatay, Pine Valley, Potrero, Jamul, Descanso, Boulevard, Tecate. The people out there were mostly older, mostly Dust Bowl refugees, living far from civilization in a time before satellite television and the Internet made country life less isolated. Many did not have telephone service, down the rocky canyons and scrub oak valleys where they made their homes. The Back Country Trader tied these lonely places together as a place that didn’t otherwise really exist as a whole.

The page or two of staff-written news was produced by my girlfriend or Glenn or the secretary who retyped press releases from the senior centers and water boards. The ads were occasionally delivered “camera ready,” especially the half-page collections of rural property for sale, but most were made in-house. We had vast piles of clip art books, from which the better illustrations had been clipped out years ago. The dregs went into the new display ads, and many of the long-running advertisements had been pulled up from the old layouts and glued down again so many times that only thick layers of cellophane tape held them together. Typesetting film was expensive. Nothing was wasted.

To fill the inevitable gaps on a page, there were shallow wooden drawers of perennials: house ads, timeless corny stuff that didn’t fit in the last issue or an issue from a decade ago, goofy little drawings of cowboys and horses and windmills. Columns of text were frequently shaken from their glue strips in transit, and the newspapers would usually have some mysterious switched cutlines and jumps. People could generally figure it out.

The readers did a lot more than just read the paper. They contributed most of the copy, week after week, without pay. It’s mostly forgotten today, but small-town and rural papers have long used their ambitious readers as free correspondents. In the Back Country Trader, all the copy from about Page 3 onward was reported and written by the lights of these tiny communities: mostly elderly ladies who kept busy with volunteer events, seasonal fairs and rodeos, church suppers, and the endless documentation of their neighbors falling ill and dying.

An Associated Press reporter visited the Trader’s newsroom in 1978, a decade before my own brief time at the paper, and not surprisingly found Glenn in a storytelling mood:

Hayes, 51, said he tries to leave the copy delivered by the correspondents as it’s written, but must watch it closely.

“There is one nice lady I won’t name who keeps trying to slip naughty jokes past us,” he said.

There were 3,000 paid subscribers in 1978, according to the AP story, and circulation couldn’t have been much different in 1988. Because I had a pickup truck and always volunteered for any pointless driving around in the mountains and desert, I wound up with the responsibility of newsstand delivery for a couple of months. On the Wednesdays after the endless Bushmill’s nights — Glenn drank the whisky, I stuck to coffee — I would load up the F150 with bundles of the weekly tabloid and deliver them to a dozen rack locations that were an average of a dozen miles apart. The collected change from the newspaper racks was mine to pay for the gasoline. I don’t think it ever added up to more than twenty dollars, but gasoline was a lot cheaper then.

Besides, I loved it. Having foolishly decided I was done with journalism at the age of 17, by my early 20s I would take anything offered — including working numerous jobs for no pay at all. Eventually I covered some boring rural town council meetings, so I could have a few bylines to take around that weren’t from a high-school paper or the local Sierra Club newsletter. My girlfriend got another job or went back to college, I can’t remember which, but we said good-bye to Glenn and his booze and his death-rattle cough and his stories.

I never saw him again and never really gave another thought to the Back Country Trader. Until putting this story down in words on this late March morning in 2013, Glenn Hayes remained as he was in 1988, sitting back in his office, sipping his chipped old coffee mug of Bushmill’s, in turns coughing up a lung and laughing at some local absurdity. But I had lost all the copies of the paper except for one yellowed clipping, one of my few real bylines there, and I couldn’t remember Glenn’s last name.

Glenn G. Hayes Jr. died in 2006. From an obituary I found online, I learned he was married twice and that both wives died, part of a chain of sorrow that included the deaths of twin sons. But it was a life that was much richer than what I had ever guessed from those nights in that cowtown newspaper’s back office:

He was a U.S. Army Veteran serving in the U.S. Army Air Force Cadet Pilot Program during World War II. He graduated with a degree in journalism from Grinnell College and did post-graduate work in aeronautical engineering at Purdue University. He was owner, publisher, and editor of weekly newspapers: The LuVerne Tribune, The Wright County Reporter, The Decatur Republican, and The Back Country Trader-Prospector Mountaineer. He was a member of the Michigan Press Association, the Arizona Press Club, the Tucson (Arizona) Press Club and Sigma Delta Chi, the national journalism society. He earned multiple news and photography awards from the Michigan Press Association. He was a 32nd degree Scottish Rite Mason and a past master of the Decatur Lodge No. 99 F&AM; of Decatur, MI. He was also active in the Order of the Eastern Star. He served as president of the Decatur (Michigan) Lions International chapter, was a member of the Dows, IA, and Decatur, MI, Volunteer Fire Departments, and was vice-president of the Decatur (Michigan) Village Council. He was a member of First Presbyterian Church of Decatur, MI. He was a licensed private pilot, an avid golfer, bridge player, outdoorsman and sailor.

But through all those newspapers over all those decades, the biggest impression Glenn Hayes probably made on this country are all the hundreds of contributors and fresh young journalists who worked for nothing or almost nothing just to have some experience on a resume and to hear his stories.

It’s all true.

Previously: An Internet Tabloid In The Time Of Comets And Mass Suicide

Ken Layne has held approximately a hundred media jobs around the world. He should’ve learned by now.