Girl Powder: A Cultural History Of Love's Baby Soft

Girl Powder: A Cultural History Of Love’s Baby Soft

by Jessanne Collins

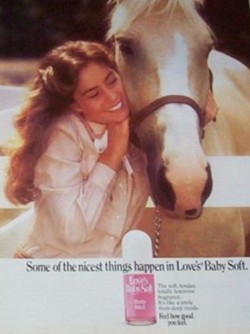

Perhaps the most feminine of all feminine products to have ever existed on Earth is Love’s Baby Soft. Its packaging, all soft curves and pale pink and frost, was basically an homage to the tampon. Its marketing scheme was Cinemaxilly soft-focus pre-teen beauty queen. It was made out of chemicals. It smelled like babies.

From the mid-70s until the mid-90s, this fragrance was an object of intense feminine fetishization for girls who had reached a certain age: the one at which we began to feel, rather definitively, not quite like little girls, not yet like teenagers. At this age, around 11 or 12, we acquire a sense that there’s a next level somewhere out there, just out of view, as if we are characters in a video game. We are consumed with figuring out how to get there. A magic mushroom must be consumed, a brick wall must be smashed through, certain totems must be collected. These, conveniently, are available at CVS: lip gloss, mascara tubes, curling irons, concealer sticks, Tampax — pretty much anything that comes in pink and is shaped like… a wand. After all, the symbolic language of little-girlhood still speaks to us.

The first in a series about our teenage fragrance memories.

In this sense, Baby Soft was pure parfumerie-marketing genius. It is an aroma that touches the comfortable memory place inhabited by scented Cabbage Patch dolls and, um, actual baby powder. It is positioned reachably, at a price-point just around allowance-level. And, in its confusing way, what it says is: WOMANHOOD.

Today Love’s Baby Soft is a sensory relic. It has close to 15,000 Facebook fans, many of whom leave messages on its wall sharing their fond distant memories of wearing the fragrance in junior high and high school (“Still love the smell of this! Brings back some great childhood memories!”). But it is still, too, a product that is for sale in the drugstore. It’s produced these days by Dana Classic Fragrances, a New Jersey company owned by Lynn Tilton, the famously feminine billionaire who invests in beleaguered American manufacturing outlets, those that make things like helicopters and fire trucks. The “femininity” industry has always been a heavy-duty one.

A CUDDLY, CLEAN BABY THAT GREW UP VERY SEXY

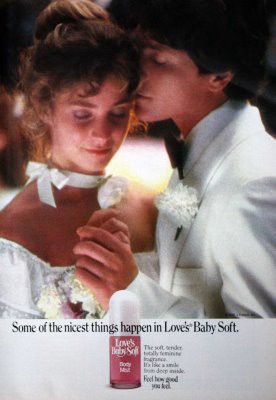

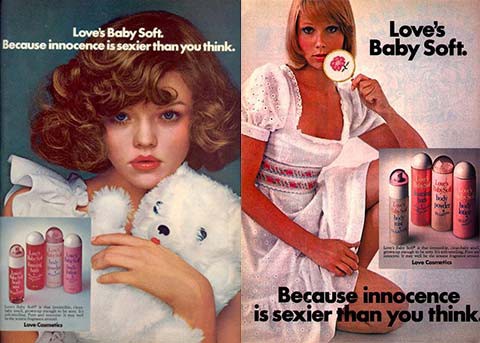

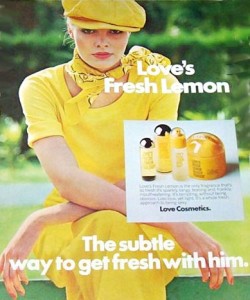

Baby Soft was born in 1974. The company that brought it to market, Menley & James, an imprint of the pharmaceutical bigwig Smith & Kline, had already been marketing beauty products to young women for several years. And yet, with the unveiling of Baby Soft, the company’s concept of “young women” was revealed to be sort of… gross. The perfume’s slogan was “because innocence is sexier than you think,” and its most beguiling, bewildering magazine ad pictured a very young girl made up in creepy-sexy adult face: a proto JonBenet. In a corresponding early TV spot, a young woman (the same one shown above) timidly fellated a lollypop as a creepy male voiceover intoned that the fragrance captures the scent of “a cuddly, clean baby… that grew up very sexy.”

To make things weirder, in the same way that Seventeen is actually aspirational reading for pre-teens, Baby Soft wasn’t so much aimed at “young women” as it was at girls who were looking forward to being women in the future. A 1974 Gimbels department store ad in The New York Times declared Baby Soft “the new way for big girls to baby their bodies” and assured that it was “created with Gimbels young customer in mind.” Somebody, somewhere, seemed confused about the difference between babies, and girls, and women. That didn’t matter: If Baby Soft was not the very first perfume marketed for the coming-of-age set, it was certainly the first smash hit.

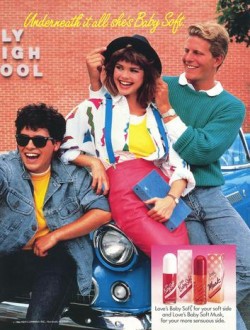

Eventually, in the 80s, the marketing angle shifted away from “sexy baby.” Instead, Baby Soft billed itself as a weapon of clandestine feminization. This was the era of shoulder pads — a time when being a strong woman was sometimes confused with being masculine. An ad from this era pictures a cool tomboy, hanging with her dude friends, and the line, “underneath it all, she’s baby soft.” Women were trying to figure out how to have it both ways; Love’s was selling girls a secret method. (This was a theme: Secret, “strong enough for a man,” would be crowned the decade’s top women’s deodorant.)

At the same time, the fragrance pulled out all the stops when it came to cornering the pre-teen market. In 1987, around Christmas time, it unveiled a “Baby Soft Cuddly Animal Prepack” containing no fewer than 12 stuffed animals, a move that, as a dry publication called Marketing Notes put it (drily), “capitalizes on pre-adolescent and adolescent girls’ lack of resistance to cute products.”

Resistance was futile; Baby Soft was beloved.

THE GIRLS LOOKED VERY COOL ON THEIR SIDE OF THE ROOM

On the topic of resistance, Baby Soft’s reliance on equating girliness with sexiness did, of course, prove fertile ground for women’s studies classes and scathing feminist media critiques. In her 2004 book Goddesses and Monsters, Jane Caputi dissected that little-girl ad from the 70s, writing:

The ad blatantly positions the young girl as a sex object and acknowledges that is her ‘innocence’ that makes her such a suitable erotic target. … It makes perfect pornographic sense. The ‘moralistic’ ethic puts chastity next to godliness and makes sex ‘dirty,’ defiling a supposed bodily and spiritual ‘purity.’ Sexual gratification of any kind then becomes all bound up not only with taboo violation, but also with defilement.

And yet, for the not-quite-woman who was not quite yet able to see past the stuffed animal to the layers of ick, Baby Soft wasn’t that complicated. It just smelled good. And moreover, it was cool. The wearer was the popular girl, with well-managed hair and correct denim — or at least, that was who she wanted to be. There were so many of her. Together they made Baby Soft so cool — its scent lingered over so much of America in those decades — that its name alone has become a kind of cultural shorthand.

Here is a school dance in Rob Sheffield’s memoir Love is a Mix Tape: “The girls looked very cool over on their side of the room, a swirl of velour and Love’s Baby Soft. The boys did not look so cool.”

Here are the contents of the medicine cabinet of a teenager navigating genders in the 70s in Jeffrey Eugenides’s Middlesex: “Two pink Daisy razors stood upright in a small drinking cup, next to a spray can of Pssssssst instant shampoo. A tube of Dr Pepper Lip Smacker… my Epi*Clear Acne Kit; my Crazy Curl hair iron; a bottle of FemIron pills I was hoping to someday need; and a shaker of Love’s Baby Soft body powder.”

Here is something more existential for Lauren Slater, in Lying: “I started taking baths, long hot soaks, my skin turning tender and red; here I am. I fixed my face up carefully…. I used all Love’s Baby Soft products, rouge in two small circles on my cheeks.”

In three words — Love’s Baby Soft — you can say a lot about “youth,” and also, importantly, viscerally: “my youth!” You can capture something of “late-century America” and a little bit of wistful “hope.” Innocence and exploitation? Sure. But the most important thing there was, then, in that bottle was the extraordinary capacity for the cultivation of self. Applied so widely, to so many selves, what there is now is an indelible ability to conjure a time, a place, a society.

IT’S BRITNEY, BITCH

Regardless of how successfully a product sells itself on multiple variously exploitative levels, it can’t maintain a four-decade shelf-life without periodic shots of caffeine and glitter. And in the 90s, perfume peddling got complicated. Fragrance companies, which had previously been content to reveal a new classic once or twice a decade, began to push a plethora of fad fragrances — suddenly women were told they needed entire scent wardrobes. It was in this climate that, as The New York Times reported, the “entry scent for young girls” was scooped up by Renaissance Cosmetics, “a company that buys old fragrances and dusts them off, gives them a marketing budget and sends them back into the world.”

It was enough to survive on, but survive was about all it could do, because things were about to get even more complicated. The late 90s, of course, belonged to Britney Spears, a creature who was more or less Baby Soft’s “sexy baby” idyll come to life. Only, it was she, at the turn of the millennium, in her plaid skirt and pigtails, who slayed the Goliath of “innocence.” Then, and this is awesomely ironic, she conquered the perfume market. In the 00s, it was Spears-brand fragrances like Curious and Fantasy that grossed billions and dominated the industry’s drugstore share. Seventh graders weren’t interested in smelling like babies so much as they were interested in smelling like Britney.

In 2005, a year after Curious debuted, hopeful Dana was out to defibrillate the fragrance again. This time, as a trade pub called Global Cosmetic Industry reported, with the “the recent rise of interest in 70s and 80s pop culture icons, the company hopes it will be rediscovered by a new generation of tweens and teens.” And with that, it hit on something.

There isn’t a whole lot of very splashy marketing for Baby Soft products these days. If you hadn’t happened upon its modest, dowdy Facebook page you might not know it still existed at all. And yet, there it is, rolling off the assembly line, an American industry still chugging, that hot pink rocket standing unapologetically between Jean Nate and Sweet Honesty.

It’s tricky to keep innocence fresh in a bottle. But nostalgia? That’s easy.

Related: When We Were “Seventeen”: A History In 47 Covers

Jessanne Collins still wears white musk.