A Fan's Notes On "Gilmore Girls"

A Fan’s Notes On “Gilmore Girls”

by Jane Hu

Each television show will inevitably teach you something, but together they’ve all taught me one thing — that is, a television show will always teach you how to watch it. The education starts early: “Barney” or “Sesame Street,” where learning to count is the same thing as learning how to learn to count. You might not realize it when you’re eight and miming the clean-up dance on “Big Comfy Couch,” but then the education continues. “Mad Men,” that excellent serial drama, directs us to observe details, little gestures, big paintings — all meaningful subtext. Even shows fairly awful at teaching you how to watch them, like “Homeland” or “Smash,” manage to convey something (don’t trust anyone, especially not us). My motto for shows such as these is “Don’t Overthink It” — it works! But I want to talk about the first show — if not the show — that taught me how to read television.

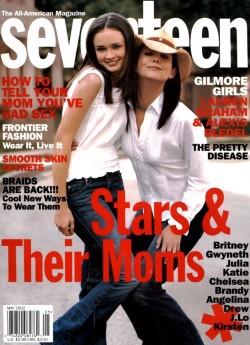

Amy Sherman-Palladino’s “Gilmore Girls” premiered in the fall of 2000, becoming the first (non-after-school, non-weekend-morning) show that I watched regularly: Thursday nights on the WB — faithfully, even if friends were over. “You’ll like it!” I insisted eagerly, in that annoyingly desperate manner I’ve yet to shake when it comes to the art of recommendations. And then, succumbing, they’d sit down to watch only to be assaulted by more fast talking, more zany hand-motions, this time emanating from the people on the screen. “Oi with the poodles!!” Lorelai and I chimed for the zillionth time (I exaggerate, but that too is the Gilmore style). My friend might ask if I could lower my voice. We were all growing up, in our way.

This essay is part of a series about our favorite TV shows past.

Previously: The Before And After Of “Monty Python’s Flying Circus”

If “Gilmore Girls” is a text, then it’s a big, fat one — in fact, double that of most evening television dramas — with heaps of knowledge to dispense. While most screenwriters adhered to the page-a-minute standard, Sherman-Palladino’s notorious ‘fast talking’ was written so that each page translated to about 20 to 25 seconds of screen time. The patter expanded so much that “Gilmore Girls,” like “The West Wing,” had to hire speech coaches to help actors through dialogue, as well as watch tapings for dropped words. (It appeared to me that one reason I spoke so loudly when was watching it was because that seemed the only way to get out all the words.) What’s more, the already capacious text overflowed with even more intertext and metatext. I didn’t entirely understand this at the time — the sheer amount of gabbing mostly worked to signal enthusiasm — but I didn’t really need to. This is the kind of television pedagogy that keeps giving. When “Gilmore Girls” re-runs started airing, I watched intently, picking up each time on a few more layers of allusion — those famous pop-culture references — previously missed the first time around.

Being an obsessive re-reader, as children often are, I wonder how much “Gilmore Girls” taught me about the rewards of continuing to be one. Lorelai and Rory were avid re-watchers themselves (the movie version of Pippi Longstocking is a “lifestyle”), as well as voracious readers and eaters: the amount of junk food consumed was always exaggerated, always enormous. And remember when we learn that Jess has read “Howl” “about 40 times”? (This is, by the way, the moment you’re supposed to fall in love with him.) In high school, I began to collect the DVDs of the show, and throughout my college years, each viewing meant more references no longer passing unappreciated. Never did it become a game or contest, though, and rightly so for no names were ever dropped in “Gilmore Girls” for the sake of one-upmanship — they were part of the fabric of the characters’ lives, which amounted to be the same, for viewers, as their dialogue. It was all so casual — knowledge of Edith Wharton’s flair for design, iconic John Hughes scenes, the opening to Moby-Dick, or the opening voiceover to “Days of Our Lives” (a combination of these four could also be used to describe “Gilmore Girls”). Those were some of the more recognizable sources, but they also get as obscure as The Thing From Another World and “Hee Haw.” (The most recent episode of Sherman-Palladino’s latest show “Bunheads” included, among others, references to Bell, Book and Candle, A Chorus Line, Judy Blume, and a hilarious transition from Tolstoy to Pussy Riot.) Sherman-Palladino’s encyclopedic script seemed endless and, in a way, it is. Dig deeper. There’s always more there. The dialogue of “Gilmore Girls” was a fantasy, but it was a fantasy that presented a deliciously tempting premise: what would it mean to know so many, and so many different, things?

So one thrill of watching “Gilmore Girls” — apart from Miss Patty’s dance rehearsals or watching Lorelai and Rory adjust to Emily in their intergenerational bonding or deciding if you were Team Dean, Team Jess, or, goodness forbid, Team Logan (poor Marty) — comes not from registering the breadth of the characters’ cultural knowledge, but in their ability to weave the high and the low — obscure cinema and popular culture — together. While I would never suggest that a balance of high-low translates to any kind of middle or middlebrow ground (the characters on “Gilmore Girls” come with all the impossible privilege of knowing so very much), the show is still the clearest attempt at a democratization of culture I’ve yet encountered. At any point, we might find ourselves acknowledging the soapy excesses of melodrama (musicals and Streisand-driven projects ran aplenty), or the show could switch and decide that Art Brut, “South Park,” or Balzac was more its taste. Oh, and taste — what did it mean in the show, if not that anything might contribute to it? “Gilmore Girls” itself aired on the WB — it was by no means HBO; it was definitely television — but its contents spilled across media, aesthetic eras, and the zeitgeisty artifacts of nostalgic pasts. Really, I’m surprised no one on the show played an archeologist. Unless that role was already being prescribed to the viewer, and if so, we were able to assume it at whatever degree we desired or could. It’s similar to the role a viewer takes on when watching “Community,” a show that teaches the viewer how to watch it on an episode-by-episode basis.

“Gilmore Girls” suggests that high art and pop culture don’t need to reside so far apart from one another. In a way, the show seems the inverse to academic cultural studies, which uses so-called high theory to read low culture, stuffing texts like “The Hills” and Taylor Swift lyrics with questions posed by Adorno and Latour. (What is the ecology of “The Hills”? Will someone please write about this?) In another way, cultural studies appears in exact keeping with “Gilmore Girls,” as it tests the line between serious art and entertainment, the avant-garde and the popular. As a writer and a reader, my fantasy is to work in a world where the Harlequin romance, a NYBR classics release, and so-called academic prose all deserve re-readings — because they can all be read seriously, each one being worth serious attention.

And so this is what I took from “Gilmore Girls”: That it was okay, nay natural, to love Stephen Sondheim and Eve K. Sedgwick, and to want to exclaim about both in a loud, enthusiastic voice, maybe even without taking a breath in between. This was part of the joys of excess I learned from the show.

To span these varying interests might make for a zany palette, but it also bears its own kind of consistency — all my cultural obsessions are fat in a similar way, stuffed from all directions. Like “Gilmore Girls,” they’re texts interested in excess — in combining what might seem too much, too much to clash — if not excessive in themselves. From my favorite academic writing (mostly, that interested in popular culture) to the musicals of Stephen Sondheim (that “avant-garde artist working in the populist art form”) or the novels of Graham Greene and Dorothy Sayers (have you read her thriller Whose Body? There are some playful Woolf references there), they all work to combine seemingly conflicting categories. They are objects that require rereading and that resist categorization themselves. They are texts that want to have it both ways.

Sherman-Palladino has mentioned Katharine Hepburn-Spencer Tracy films as inspiration for her dialogue, and while the banter of films such as Adam’s Rib and Pat and Mike certainly bear resemblance to conversations in “Gilmore Girls,” the show seems more generally symptomatic of that entire genre of talkies. Howard Hawks’ film His Girl Friday is notably referenced multiple times in the series, as is the television show “I Love Lucy,” whose heroine Lucy Ricardo, bears more than a little resemblance to Lorelai’s slapstick demeanor. But besides the more exaggerated physical comedy of “Gilmore Girls,” its dialogue is what bears the greatest imprints of the show’s 50s influences. If you’ve watched Alexis Bledel on screen since her period as Rory Gilmore, you might be disappointed by the fact that she appears somewhat deflated, not quite as bright as you remember her. I suspect this is partly because, in “Gilmore Girls,” exposition, character development, and plot moved for the most part through conversations, rather than from acting. The show never rests on monologues, the internal thoughts of one character, unless in a performance of rambling monologue before another person (Lorelai and Rory frequently rant at one another), but even then the acting is emphasized as acting. Banter gets viewers from one place to another without giving them much time to consider how, and to stuff banter with references that branch away from the topic at hand cuts their contemplation time down even more. While some dialogue teaches us to move through the world by conveying much while saying little, “Gilmore Girls” showed me how to convey much by saying much around the thing that one is trying to talk about while never actually stopping on the exact thing one is conveying much about. Henry James also taught me lots about how to do this. We’ve been here before; I recognize that tree.

Previously in series: The Before And After Of “Monty Python’s Flying Circus”