Real As Hell: A Conversation With George Saunders

While interviewing author George Saunders last week on the release of the audiobook of his new story collection, Tenth of December, my Skype connection cut out maybe four times. Such a miserable and embarrassing development on so many levels — maybe the worst being that Saunders is one of the best talkers I’ve ever met, and in the middle of this incredible riff his voice would just float and burble off, culminating in that awful, plopping Skype disconnection sound. Indescribable, like getting a long letter from Oscar Wilde and someone sets fire to it as you’re reading, or you’ve just been poured a delectable glass of Château d’Yquem and suddenly there is a massive earthquake and it’s splashing all over the place.

Manfully resisting the urge to hurl my laptop across the room and stomp on it screaming until it was a pile of shards, I reestablished our phone connection, gave up on making a Skype recording, and resorted to taking notes for the last part of our talk. Which turned out to be a blessing in (a very very good) disguise, because Saunders most graciously agreed to proof the results of my notetaking over email. What revelations came then!

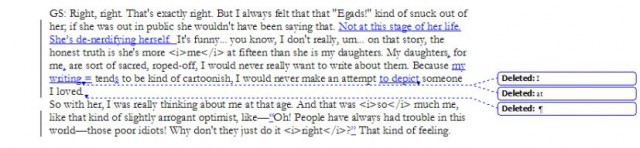

I try to be very careful about transcribing interviews into text as I go, thinking over stuff like, well, was that a dash? Or was it maybe a semicolon? So when I sent along the transcript of our talk, part of it was as faithful a recording of the author’s speech as I could make, and the rest the sketched-in notes. Which came back shortly thereafter — marked up, edited, augmented, with comments. And thus it was that I learned a great deal about George Saunders’ working methods not only from the conversation that follows, but from its eventual documentation. There was careful, very careful rephrasing of line after line (an example is below). He had his own ideas about certain exclamation points, ellipses, commas. In fact, this amiable perfectionist thought one of my questions could use a little tweaking. The author is famous for reworking his pieces over and over, sometimes taking years to finish a story. And even in this interview, one of dozens he’s had to conduct in recent weeks, the layering-up of his attention resulted in a document of far, far greater richness and clarity than the original.

And another thing: he’s a two-spaces-after-the-period man.

***

Maria Bustillos: This audiobook is just GREAT.

George Saunders: Oh, thank you so much.

You went around saying in interviews, though, that you can only do like four voices? What a fibber! You’re like a cast of thousands, in this thing.

I was already a terrific fan of your title story, “Tenth of December.” But for me, “Victory Lap” (subs. only) was hugely improved by being read aloud, while I think I maybe preferred reading “Tenth of December” to myself? Just a little bit, but I thought, why should that be? Maybe it’s more internal of a story? Do you feel, yourself, that some of your pieces read out loud are better, and others read to oneself?

It might also be — this is maybe sort of mundane, but I’ve read “Victory Lap” a lot, over the last year or two; when I go out and do a big reading, I’ll read that one. So I’ve kind of got it down a little bit, the rhythms and stuff. I think, “Tenth of December,” I read it once for the New Yorker, and the audiobook would only have been the second time I ever read it.

So I have a feeling I — for example, I have no idea how to do that little boy in “Tenth of December”; I’ve never quite stumbled on the right way to do him. So it might just be, if I did it a bit more, I would —

Oh, that’s so interesting! Because you really are able to voice — for example, Alison [a fifteen-year-old girl], it’s amazing to me how evocative your reading is.

It’s a little spooky for me. It’s almost like, when I was writing those stories, I could sort of “hear” a voice in my head, and then channel it down. But the voice I can hear is much more subtle than the one I can actually perform. So as I read it out loud over and over, it’s as if I’m working my way back to being able to do that Platonic version. But because I’m not an actor, I never quite get it exactly; she reads a little more broadly to me when I read it out loud. And you get more laughs that way, but I think maybe she becomes a bit more cartoonish in the out-loud reading — she’s a little more of a space cadet. Whereas when I was writing it, I felt she was pretty bright, and I don’t really disagree with the things she says.

Oh, no! Nor do I. (“Egads!” — I love how she talks.)

Reading is a totally different skill set. Performing your stories is kind of a plus, it’s helpful, because the gigs are, you know, reading. But what if Henry James had had to go to Barnes & Noble, you know, that would be… a little hard to take, maybe — but it’s still great writing.

I was completely zero surprised to hear that you have daughters; there’s that moment, so specific, where they’re on this really magnificent sort of knife-edge between childhood, and being really snarkily dismissive with their sort of sexual power at the same time.

Yeah, it’s interesting.

Isn’t it? But like, Alison and Kyle had been friends earlier, I thought, because they BOTH would say “Egads!”

Right, right. That’s exactly right. But I always felt that that “Egads!” kind of snuck out of her; if she was out in public she wouldn’t have been saying that. Not at this stage of her life. She’s de-nerdifying herself. It’s funny…you know, I don’t really, um…on that story, the honest truth is she’s more me at fifteen than she is my daughters. My daughters, for me, are sort of sacred, roped-off, I would never really want to write about them. Because my writing — tends to be kind of cartoonish, I would never make an attempt to depict someone I loved. So with her, I was really thinking about me at that age. And that was so much me, like that kind of slightly arrogant optimist, like — “Oh! People have always had trouble in this world — those poor idiots! Why don’t they just do it right?” That kind of feeling.

My husband’s famous phrase to describe the worldview of a kid. “How could anyone possibly object to me?”

[Laughter] “I’m here! Don’t you see?” I think that’s deep. We think of kids as being kind of dumb, you know; they’re inarticulate and they don’t know how to start a car, and so on. But when I think back to being five or six, I can remember a fully-formed human consciousness that was very sophisticated, and very judgmental and very egotistical.

Oh man, I’m right with you.

— and very discerning. But I suppose, you know… at that age, you can’t speak it, but I remember being very… complex. Like when Kennedy was killed, it was 1963, so I would have been about four. And I have a really distinct memory of standing in the driveway, and this friend of my mom’s came flying by, distraught, and I remember being very offended that she didn’t say hello. I was like, “Who do you think you are?! You just went right past me, madam!” And I went upstairs and they had turned the TV on and were crying, and I just remember my reaction was: “Who’s this dude, ‘Kennedy,’ who’s usurping all my attention?! Like, Mom? Hello?!”

And then you’re capable of being overtaken by really, really serious emotions, but you have no defenses against them.

That’s right, they just come on you like a storm, and you don’t know what to do with all of that. So I’m interested in that. In those internal monologue things, I’m trying to take away the overlay, the habitual way we think about thinking, and just say, wow, if you could really drop into a human mind at any moment — look what’s actually going on in there, it’s crazy shit! — it’s multi-level, layered, and confusing and contradictory, and poetic and all that kind of thing.

I love the tension in your stuff between innocence and experience. So much seems to kind of hinge on that, between recovering the innocence of adults, and children losing it? Kyle — this is one of the great crescendoes in literature, for me. When he’s running, it’s so good — I’m sorry, I’m just such a superfan, so this interview is going to sound really idiotic.

I’m loving it so far. Keep going. I’ll just every so often go “uh huh” as you praise me.

Okay but I have real questions too! I do. Talk to me about Catholicism.

Okay. Are you Catholic?

Cradle Catholic, yeah. Utterly lapsed, but there you go.

Right. Well, for a lot of years I played it for laughs, you know, like the “inner nun” and all of that. But recently I was thinking about the Stations of the Cross, a lot. Did you do those, as a kid?

Yes.

I was thinking about how profound that is, as a fictive exercise. As I remember it, you sit there, and there’s a little bit of a reading from the Gospels, talking about the scene, and in our church they were these kind of highly Seventies-stylized pictures of the different stations. And I kind of remember being encouraged by the nuns to visualize and to think: “Okay, what’s Jesus thinking? What’s Mary thinking?” And even: “What are the Romans thinking.” So, that was deep. To be sitting there trying to imagine what the murderous Centurion was thinking as Jesus stumbled past…

I think as I become older, I’m becoming more and more grateful for that rigid Catholic background, on a lot of levels. The language training was terrific — the English stuff was great. We diagrammed sentences and that whole thing. But also in Chicago when I was growing up in the Seventies, there was a lot of that kind of Dorothy Day activist component going on, and at the time I thought it was the coolest religion, because, compared to my perception of the Protestant church, it was so in the world, on its feet and sort of activist. It was all about Jesus as an advocate for change. I loved it; and I had a couple of really deep experiences in church that were — one in particular where I just had this — I can’t really even articulate it, but it was just this profound feeling of connection with the lineage of the Apostles, and so on, just real as hell, and also the feeling… this fear that that heightened feeling would fade. Which, of course, it did. That night we went to dinner at a friend’s house, and I could feel that feeling waning, and it felt bad, because I was just in this incredible zone where I thought: Wow, now I know how to live the rest of my life; and it was like, living for others, and living in a state of love, and I just felt it like a total buzz; and then it started to drift away, and I lost that feeling. And that really was a sad thing. I remember my friend and I were playing this board game called “All-Star Baseball” or something like that, and part of me knew I had to be a regular kid, and play the game, but with each turn I could feel that exalted feeling diminishing more and more…

I don’t know if I’m answering your question.

Well, yeah, obviously, I want to hear all this! And I had this other thought about it… when I first read your work, it was strange, I don’t know why I thought this, but I thought: this guy grew up Catholic. Right away. And I thought, well, why do you think that?

Also: I went to public school, where we also learned to play religion for laughs all the way. We used to rib each other mercilessly. Kids from all these different backgrounds, there was no other way to deal with it.

Did you call them “publics”? In the Catholic schools we used to say, very sorrowfully, or disdainfully: “Oh she’s a public.”

No, we didn’t have that! I never went to Catholic school. But I went to Sunday school and was about to be confirmed, when I finally quit. I’d asked whatever nun, what the heck, I mean, what if you’re from China? And you’ve never heard of this ever, and you’ve lived a perfectly blameless life? And she goes, “There’s a special place for them.”

Yeah: Hell! A really special place.

But I loved growing up Catholic. There was something so powerful about the way they respected metaphor, and all of the symbols, and the incense and so on. They expected you to understand that there are truths that are not overt, but implied, and that the best way to imply that kind of truth is through metaphor and ritual. I think that once you get immersed in that kind of beauty, and really feel it, even once, you will always be looking for that. Which is maybe where art comes in later. There was some kind of correspondence between the early, sort of sublingual kind of magic in Catholicism, and the desire to kind of get back into that space.

I felt this too.

Another thing: guilt! You have a lot of guilt in your work, and it seems to me to be of a very Catholic flavor. What is that?

Well, I think my guilt kind of predates my Catholicism. It’s like birth-guilt or something. I think the Catholics picked up that preexisting guilt in me and sort of super-charged it — but it was already there. I have really early memories of feeling inadequate: arrogant, and inadequate at the same time; I think that’s neurological maybe, I don’t think there’s any… I don’t know. But I’ve always felt not quite up to the task. The task of living, you know. So I always felt a lot of real fondness for life, and a kind of enthusiasm for people, somehow linked with the feeling that I wasn’t quite good enough to be at the party. So you add those things together, it equals a desire to achieve something. I felt like: if only I can DO something, I’ll be worthy of all of these people and all of this beauty. Not exactly, uh, a high-functioning mental attitude. But there it is. So I know better, but that’s how it felt to me, always.

Do you think there’s such a thing as “Catholic guilt”?

Yeah, it’s taught, certainly. At our school, when you did something wrong, there was a vague sense of, “Oh yeah, you would do that.” Plus Christ died for your sins. But guilt… my sense is that it has a lot to do with that other set of delusions that we are born with. The delusion of your own permanence, the delusion of your own centrality. So if a person says, I’m here, I’m born, I’m three or four, I am the center of the universe; everybody is here for my amusement… Well, that is an intensely egotistical position, and there’s a backlash for it. The guilt might be sort of the backside of that. If you’re responsible for all reality — well? That’s a lot to take on.

Also, guilt is funny, comical. Guilt is ego, actually, when you think of it. If I’m at a party with you and I’m trying to be clever, and I say something hurtful and afterward I feel guilty about it, in a way that presupposes that I should be so in control that I would never make a mistake — that’s ego. The thought that I — I, so perfect and above reproach — would never make a human blunder. Which is — you know, that’s very egotistical, to understand yourself as He Who Never Blunders.

Maybe guilt is also: I could have done better. I am, or I want to be, better than this.

So I suppose a preferable moral position would be (1) make the mistake, (2) go: oh, I see, interesting, this person that is “me” just made a mistake, (3) very calmly assess, to see why that happened and (4) adjust as necessary. That would sort of the ego-free version. Me, I tend to get stuck at (1), and then a modified (2), which is: You big idiot, how could you do that, you suck.

Ah. Yes, eek, I’m familiar. Though in the Saunders universe, the world of your books, everybody is constantly aware of his capacity to blunder.

Yes. As is the case in my head.

That’s what I love about it so much; there’s such a lack of that in fiction, where people generally are chugging smoothly along on the preordained paths of their intentions, fulfilling a “role.”

Hmm. Right. I don’t know how other people’s minds feel to them, but to me… I’m really aware of all of those funny little micromoves we do in our heads — the little swellings of pomposity, the crazy unlikely mini-fantasies (“And then President Obama calls me, and asks me to write a speech…”) And my working assumption is that, if I put those things into a story, the reader will rise to them — will go, “Aiyee, I do that too.” And then…we’re more connected. So when I put those things in, it’s sort of a rhetorical moving in the direction of assuming that everybody’s shit is basically the same. Our minds basically — basically — do similar things, in a given situation. So that is the basis for that effect in fiction, where someone from another time, long dead, rings your bell from afar.

When I was younger, all my heroes were very Hemingwayesque, and aloof and powerful and in control. They knew what they thought, and did what that thinking told them to do, and so on. And then at one point you get a sense of the disconnect between the way you’re actually functioning in the world, and the way your characters are moving around, with trenchcoats, and attaché cases and perfect haircuts.

If the two of us go to a real fancy party, I am probably correct in assuming that the two of us feel basically the same about it (of course, with some variations). So a lot of comedy comes from that. Somehow this also brings to mind the joke about if there are two people in an elevator and somebody farts, everybody knows who did it. What’s funny about that is that little instant where farter and non-farter are on the same page, so to speak. So I love the fictive equivalent of that — that willingness to look at the minutiae, that maybe your prideful self would have you look past. To be aware of all of the little mind-blips and hesitations and so on — that is really the root of the comic, for me. To let out into the open those things that we normally edit out in the re-telling — even if we are only re-telling it to ourselves.

When I was younger, all my heroes were very Hemingwayesque, and aloof and powerful and in control. They knew what they thought, and did what that thinking told them to do, and so on. And then at one point you get a sense of the disconnect between the way you’re actually functioning in the world, and the way your characters are moving around, with trenchcoats, and attaché cases and perfect haircuts…

Which is fun, though!

Trenchoats and so on are totally fun, yes. As were — you know — stories about fishing trips or stories where no one actually worked and so on. But in my case they started to feel so false — such a betrayal of what life really felt like, both out in the world and inside my mind. So at some point I think the youngish writer has to make a choice: either continue to inhabit the world of his masters, where he is always going to feel like an imposter, or go down (and it really felt like down to me) to his own fictive world, come what may. In class I do this drawing of this big mountain, that I call Hemingway Mountain. And talk about how, early in my writing life, I just wanted to be up there near the top. And then I realized: Shit, even if I made it to the top, I’d still be a Hemingway Imitator. So then you trudge back down — and look, there’s Kerouac Mountain! Hooray. And then it’s rinse, lather, and repeat — until the day comes when you’ve completely burned yourself out on that, and you see this little dung heap with your name on it, and go: Oh, all right, I’ll take that — better to be minor and myself. So that is painful. Especially at first. But it’s also spiritual, in a sense — it’s honest, you know. It’s a good thing to say: Let’s look at the world as it is, as opposed to the way I’d like it to be. Let’s see how the world seems to me — as opposed to the way it seems to me, filtered through the voice of Hemingway (or Faulkner, or Toni Morrison, or Bukowski — whoever).

Yeah, wow.

[Long pause (also, on the part of the interviewer, a little vertigo).]

Hmm.

Can we talk about Syracuse? [That is, the graduate writing program where Saunders is a teacher.]

Sure.

So you were saying there are six hundred applications, to choose six people, in your program.

566 this year. Actually I am supposed to be doing that this afternoon.

So tell me, what makes someone one of those six, for you?

It’s really a weird process. I don’t think we’ve ever been able to articulate it, but it’s maybe like that old definition of porn: you kind of know it when you see it. The weird thing is, we’ll have usually four of us, reading. And when we get together at the end, we always agree on the top ten. For sure. Maybe when we go to six, then there’s a little quibble. But I think making it into that top six has something to do with an eagerness, and a willingness, to communicate directly with the reader. The person really comes through, and there’s an openness and an understanding that what she is about, is communicating something urgent to another intelligent person. On the other side — the people who don’t make it in… maybe we can feel that they aren’t so interested in communicating, but more in impressing. It’s hard to generalize — there are so many applications and generally so, so good. Last year we agreed that we could have gone as deep as #75 or so and still been VERY happy to work with those people.

You read thirty or forty applications, and go, “Maybe, maybe, I dunno”… and then someone comes along and you go, Ooh HERE’S a human being. An urgent, human voice. And that’s very exciting. Other problems, like with structure, you can work with those. But there’s not a lot of debating among us, generally; the cream really does rise to the top. On the one hand it’s a lot of work — you dread it — but on the other it rewires you, makes you see again as a reader.

It wouldn’t be ethical, but it would be so great if our current students could read that pile; there are so many commonplace moves in fiction. If you could learn about those in advance, you could sort of veer away from them. You know, the things that we all habitually do as writers. And that, reading at that volume, your eye tends to race past.

When interviewers have discussed your own originality, you’ve sometimes commented on that as maybe having to do with a lack of training as a writer. And yet later, you got all the training, and now you teach. And all that’s happened is you’ve gotten better and better: so?

It wasn’t so much that I wasn’t trained, but that I was coming into writing from a weird angle. I had the engineering background and wasn’t very well read in postmodernism and came at fiction from a very traditionally realist, Steinbeck-Hemingway-Thomas Wolfe place. So it was like if you learned to hit a baseball without ever seeing a professional swing. There was a sort of functionality in what I was doing but it always — still does — look a little odd. This unusual quality, that I feel like I picked up from coming at writing from a weird place — it helped, but also maybe hurt? Because, for instance, when I came to Syracuse I hadn’t had the experience of reading dozens of novels, and that might be why I haven’t written one. I think if you read a lot and well as a young person, that loads you up with a sort of deep knowledge that is very helpful, and makes you confident — I feel like that’s maybe what I’m missing — that feeling that would come from having engaged deeply with newer novels, when I was a young guy, coached by people who really knew that work. But during those years, I was in engineering school. For better or worse.

But now I wish… I think it would be fun [to write a novel]. I love that thing you can do in a novel where you are riffing on something just because it’s fun, absent the constant pressure of escalation that is a necessary part of writing short stories. Just those wonderful digressive riffs in a novel that earn their way by being great writing, even if they are peripheral to the “real” story or a little digressive. A story doesn’t leave much room for things like that.

Yes. I endorse this idea of you writing a novel, and I am certainly not the only one. That brings me to the matter of your audience, because I guess suddenly you are so famous, now? Which came as a complete surprise to me, because I thought you were a superstar already.

Ah, it’s hard to know about any of that. This one’s actually selling, which is new, and very nice; the others had good reviews and so on, or mostly good reviews, but they didn’t really sell. So that has been interesting. But… a year ago, I was perfectly thrilled with where I was: it was sort of perfect. I had everything you could have as a writer, but at a cult level; good responses at universities, things like that. Lots of peace and quiet. I think if we had talked then, though, one of my concerns would have been: OK, am I finding my full audience? And if not, is that somehow my fault? Am I somehow writing in such a way that good, serious readers are put off? Is there some sort of stylistic tic I am guilty of that is not essential to going deeper, and is having the effect of ghettoizing my work? So now… well, now I don’t know. I just heard that the book is coming in at #2 on the next NYT list, so that is amazing. At 54, I’m very happy, it’s like, okay. Wow. And it has made a really interesting, sort of anthropological, opportunity to look into parts of the culture I didn’t know about (TV, for example, and the things that happen when a book sells, just in terms of demands on one’s time and effect on the mind/ego, etc. etc.). And also it has been great to meet so many readers all over the place. It’s made me feel really good about the state of American literature, to see and meet so many articulate people, for whom writing and reading are so important.

This is very interesting to me. It’s a rare thing, when there is a keen pleasure to be had on the surface, but the work continues to repay the investment of attention (cf. Austen, Shakespeare, Springsteen, Wodehouse, Louis C.K.) What do you think about “difficult” vs. “easy” in fiction?

Well, I think you’d want to be as difficult as you need to be, you know? I’ve often thought that when we find ourselves situated on a binary (i.e., experimental vs realist, or difficult vs accessible) the most interesting answer is along a different axis. That is, I can’t imagine anyone interesting saying, you know, “I will ONLY write in a difficult mode!” Or: “I refuse to be anything but ACCESSIBLE!” The point would be to have your eye on a different goal — so, if we said, “My goal is to evoke deep feeling in an honest way,” for example — well, would that prose be “difficult” or “accessible?” And the answer would be: Both. Yes. Or neither.

Do you still read and/or enjoy genre stuff? Did you grow up on that, or were you mostly a reader of serious fiction?

I was never a big sci-fi person although I did see a lot of sci-fi and horror movies. I also read a lot of sports books and a lot of genre books about WWII — stories about famous pilots and so on. Then I had a period in high school and college where I was reading a lot of sort of schmaltzy light philosophy-type stuff — Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance and Kahlil Gibran. And an Ayn Rand phase. We used to get those Reader’s Digest Condensed Books and I’d plow through those…

So what does it do to your ego? Or rather, what does it to do your ego.

Well, it’s roughly like a sugar buzz. You get some praise, you are all modest about it, at least on the surface, and then almost immediately start craving more good news. Or — it’s like eating beans. If a person eats beans, he’s going to get farty and bloated. That’s just… the body. So the trick is maybe to just hold back a little bit and observe the process. Huh — here the metaphor gets weird. But anyway — so far, so good, and I think these many years of writing have been good training — I really am just getting hungry to get back to work and try to, like, live into all of this attention, and do right by it, in the next thing.

So you have this huge, diverse audience, now. Let’s talk about all the terrible Amazon reviews you have!

Haha, yeah. My friends are very politely saying, well, it seems like your book is very polarizing.

I don’t have the nerve to actually read them. But my guess is that a certain number of the people who came to the book from the Times piece, or from seeing me on TV… I mean, I come off like a nice guy — I mean, I am a nice guy… and maybe, when I talk about it, the book seems a little more, uh, Chekhovian or happy or something, and also more accessible, so… the book might not be quite what they expected?

Oh yeah, I think there might be a lot of people who aren’t realizing that it’s actually a very scary ride, not just a fun one.

Yes. It’s dark. I’ve also heard some talk about it being difficult — which, to me, it’s not that difficult, particularly, especially to those of us who read a lot of contemporary fiction. But it’s possible that, with the Times piece and the TV and so on, people who don’t normally read contemporary literary fiction are finding it, and that it might be surprising to them. But within that group of people who’ve found it, I’m hoping, there are also people who don’t normally read contemporary fiction, and — like it. And I’m getting emails and stuff that indicate this is the case, which is nice.

Until the day comes when you’ve completely burned yourself out on that, and you see this little dung heap with your name on it, and go: Oh, all right, I’ll take that — better to be minor and myself.

As for the darkness… I think about that a lot. The real and primary truth is contained in that Flannery O’Connor quote about how, you know — a man can choose what he writes, but he can’t choose what he makes live. When I follow my own energy, I tend to set stories at the end conditions — those days when things go wrong. That’s not entirely new — I mean, that’s storytelling. That’s the Crucifixion, that’s the Garden of Eden, and so on. So I think a sophisticated reader understands that, if you put a baby near a cliff, you’re not saying that all babies live near cliffs. You’re just saying: what if there was a baby near a cliff? And/or you’re saying: isn’t it the case that, sometimes, babies get near cliffs? And/or: doesn’t life sometimes feel like you’re a baby and you’re near a cliff?

There’s a school of thought that understands stories as being the reflection, of life, in very clean and non-distorting mirror AND thinks the writer should make sure to point the mirror at “average” or “typical” situations, AND makes sure that the events of the story produce some kind of “uplift” or “hope.” I don’t really… well, I don’t really have a gift for that kind of story. I think whatever hope or uplift a story has can, in a completely valid way, come from the way in which the story is told — the verbal energy, the humor, and/or the ways that, in a terrible situation, a person may rise — or merely even try to rise — to the occasion.

So, to me, fiction at its best is not supposed to just be this flat, perfectly reflective mirror, that presents a linear position of “life as it is.” We should expect and enjoy some distortion in the baseline representation. I think we do this all the time. I mean, let’s say you’re watching “Charlie Brown”… nobody turns it off because they’re thinking, “Hey, no one could actually stand up, with a head that big.”

[Laughter]

That’s not exactly fair, you know? That viewer’s not being a good sport.

Reading fiction requires a little bit of that willingness to be a good sport. To say, you know: I will grant you, writer, your initial offset, whatever it is — darkness, talking forks and spoons, you name it — but I’m going to judge your artistic efficacy on what you do with my faith. It would be a bad or ungenerous reader who’d say: “Wait a minute, Kafka, we all know that people don’t transform into bugs. I quit. Your story sucks.” What really makes or breaks a writer is what he does with the initial set-up. “If I grant you that Gregor turns into a bug, what will you do with that, what will you show me about human nature that I couldn’t otherwise have seen?”

But anyway, I love that there’s dissension and so on. It’s great, too that people are reading it, maybe being challenged by it.

Right? Even if it’s so weird to you that maybe you don’t like it at first! “The Rite of Spring,” or whatever.

Yes. And if you don’t like it, take it back! You can return it. [laughing] Get your money back!

But I can see that a lot of this is just… when you get to a certain level it’s just like, you have to put on the big boy pants. You have to have kind of a thick skin sometimes. I don’t, really not naturally — I’m kind of a defensive person. But you have to accept that, if a lot of people are reading your work, there are going to be a lot of different reactions, and the fun part is, to be out there, in peoples’ reading lives. I mean, if we’d talked before the book came out, I might have said, fiction has such a small audience. It’s largely read by other writers; we’re ghettoized, we’re in this MFA bubble. (All of which really meant: MY fiction has such a small audience, I’m ghettoized, etc. etc. Ha.) I think my concerns, back in, say, November, would have been to figure out a way to get my work out to those X number of readers who would get it if they only found it. And I think we found them. As well, apparently, as some people who found it and maybe wish they hadn’t. Based on the Amazon reviews. But more the former than the latter, it feels like.

But really, this is great. It’s fun. To be read, and to create a little friction — good things, really. I think it’s important to remember that art is a game. A big, high-stakes game, that takes so much of its energy from being like life, or about life, or from life — but still, a game.

When you are threatening innocents, like, say an animal, in your stories, it’s a mark of your skill that I will even make that trip with you, on account of my being totally unable to take the idea of a beast in danger (this is forever for me, in your work, since the raccoons years ago.) Like when I see one in a movie — you can always tell a doomed beast in the movie — I’m basically diving under my seat and avoiding the whole thing; an old boyfriend once invented an advocacy organization just for me, the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Fictional Animals.

In any case, when you in particular endanger someone, it will throw even a reader who is very familiar with your work into a complete panic, because this thing could go either way. You’re not necessarily going to rescue anybody. You never know how it’s going to go.

I never know how it’s going to go. It’s true, I never know how it’s going to go. That would have to be the case, I think — I mean, if you are really writing openly, and the energy of the story said a bad thing had to happen — then there you go.

One reason, though, that I tend to put animals and kids in danger and so on, is just a lack of subtlety. I don’t have a real finely developed sense of finesse and so, when seeking drama, I just tend to grab the nearest and most innocent thing and… menace it. Or like, in that story “The Barber’s Unhappiness,” when I was trying to increase my feelings (and the reader’s feelings) for the main character, who I’d been parodying pretty fiercely, I just suddenly found myself stating that he’d been born with no toes. Bango! Sympathy.

In writing, I think we are often just trying to get into relationship with our own weaknesses and deficiencies and, by fessing up to them, trying to convert them into assets.

That is the real uplift. The rest is just Hallmark bullshit. You fess up, I fess up, we share all these incalculable weaknesses, shocks, terrors, failures (delights, jokes, also) that we’ve survived. And look quietly back together. Now what?

Exactly right. The uplift is: a thing done honestly or well. We like seeing someone else in a state of transport — even if the “frame” of that state of transport is “dark.” I think of music, for example — think of the saddest song ever, but if it’s done beautifully, you feel “uplifted” by the singer’s passion or presence.

What I feel most is the not-alone thing; I’m so comforted, because there are at least two of us, now. (A couple of babies at the edge of the cliff, you might say. Hand in hand, listening to the pebbles rolling off the edge.)

I read some, not a huge amount, of modern fiction. But you seem to me to be unique, or nearly so, in the degree of focus your work has on the reader’s attention, moment by moment, anticipating what I’d be thinking or feeling. How much of this is deliberate?

You’re describing 100% of my process. That’s the goal. To know where my reader is at any moment and do the next thing with that in mind. Though I can never be sure, exactly, of course, that I know what the reader is really thinking at any given moment… but you try to simulate that state…

Oh yes you do. Allow me to tell you — certainly yes, you do, rest assured.

What I do is try to simulate the experience of being a first-time reader. I imagine there’s a sort of meter in my forehead, with P for Positive on one side, and N for Negative on the other — and the process of revising is just reading what I’ve done, while trying to posit where that needle would be for a first-time reader, and adjust accordingly. So when I rework something, I’m trying to get back to that experience, of reading for the first time…

It seems like there’s a danger that reworking would almost necessarily take you farther away, instead of closer, if your focus gets too far in…

That’s exactly right. It does. Your own words become a bit dead to you. What I do is, I try to figure out tricks to help me readjust my eye, sort of reset my capacity to see it as if for the first time.

Like what kind of tricks?

There’s maximizing the time between reads, for example. Or now I can sort of reset… I have the capacity, more or less, to reset at will. To — it’s hard to talk about — but there’s a little mental adjustment that, if I can do it, clears the slate, so to speak. It’s just a little mental adjustment that I have a hard time describing.

But the main thing is — to be patient. Go through the piece many, many times, making small adjustments each time. There’s a sort of saving grace in this iterative approach — the truth will gradually, mysteriously, assert itself. If you iterate enough, the piece will increase in clarity, intelligence, humor, and kindness: your vision will become more sympathetic and true. I can’t really explain or defend it — but I know it’s true for me. It’s as if going through a piece many times gradually chips away at my habitual falseness. It’s maybe like — if someone asked you a hard personal question and you had to answer it in 5000 words, on film. And then you got to come back, day after day, and slightly alter your response. Over time — if your intention was to tell the truth — your account would get more and more honest. And in fiction, honesty means — well, complexity and ambiguity and — and this is the weirdest part — it means that you gradually give your character more credit. Even if he’s a bad guy, you start looking at him deeper and understanding his motives more generously.

It’s like, as you edit, your moral capacity to understand what you’re trying to achieve can become larger, and more clear?

Yes, exactly, that’s exactly right. Like in the title story, “The Tenth of December,” there’s a guy maybe minutes from death and he’s thinking about his son, and at first, I had him thinking something about his son’s wide hips — something harshly physical, something meant to be a little funny — but it was sort of mean. Later, I thought: In that moment, would he be so critical of his son? And when I changed it, it felt truer — more like him.

Oh god though, but it’s just so great, how he is able to see his son with this gimlet-eyed clarity, the truth of him…

But in the final version I softened this — he sees a certain moral weakness his son has, and sees it very gently — but the earlier little barb about his son’s looks is gone now.

Yeah.

— and it felt so much better.

[A silence, here.]

So the reader might be thinking, “this is dark!” or “this is scary!” and you notice that, or know that — and then, in response, you leaven it with something else. You’re basically saying, “Yes, I agree, this is pretty dark. Let’s see if there’s anything else here, so that you and I, dear reader — who, of course, live lives that are not dark — can feel some connection with these unfortunate characters.” These feel like language adjustments, but it’s what you said: they’re essentially moral adjustments.

Related: The Joys Of The George Saunders Style Sheet

Maria Bustillos is a Los Angeles-based journalist and critic. Photo of Saunders by Chloe Aftel.