How To Fail At Journalism In Exotic Foreign Lands

Budapest had never been my favorite European capital, but a job in a foreign city is always better than a job wherever I happen to be living at the moment. This is why, on a balmy Southern California morning in February of 1996, I voluntarily carried my only possessions to Los Angeles International Airport’s Tom Bradley terminal the customary three hours prior to departure. The first two hours passed pleasantly at the airport lounge, where my friend Steve and I drank double Greyhounds served in pint glasses.

The Double Greyhound is just a lot of vodka with grapefruit juice to soften the blow. We had been drinking these regularly in El Segundo, the LAX-adjacent working-class town noted for its sewage treatment plants and oil refineries. El Segundo means “The Second,” and the name comes not from California’s Old Spanish past, but from Standard Oil, which built its second West Coast refinery on farmland between Santa Monica and Manhattan Beach. Steve lived in a battered apartment complex with abandoned cars in the parking lot and an unobstructed view of Los Angeles International Airport. The noise was astounding. Each takeoff and landing made the windows rattle as beer bottles and drinking glasses walked themselves off the countertop and shattered on the yellowed vinyl flooring. It was so close to the airport that I had moved in for a week or two before my flight to Hungary, just to make sure I didn’t miss the plane. The successful budget traveler always plans ahead.

“When’s your flight supposed to leave, anyway?” Steve’s face had become blotched with patches of bright red, an allergic reaction to the vodka.

“About an hour,” I said, consulting my mail-order diver’s watch that I had actually purchased from an ad in the back of Parade magazine. My computer, paperbacks, magazines and toothbrush were in a black fake-leather laptop case. Everything else I owned was in a blue canvas duffel bag. We headed for my airline’s counter and found it mysteriously closed for the day. This should have been appreciated as an omen, but a nervous interlude resolved peacefully when I was transferred to a Lufthansa flight that would end up landing in Budapest only an hour later than originally planned, due to some kind of layover witchcraft.

“Considering I’ve got another couple of hours, I could really use a haircut,” I said.

Steve nodded gravely. “There’s a barber shop next to that bar in El Segundo. But then I really need to get to work.”

We eventually said good-bye at the gate — there was no security to speak of, in 1996 — and I settled into my economy seat, on my way to another newsroom on the other side of the planet. Steve went to his own newsroom, where he edited the entertainment section for a weekly beach town newspaper. (And by “edited,” I mean he wrote all the articles and headlines and did the layout. The community journalist is expected to wear many hats.) My plane was half empty and because it was a European carrier, smoking was still allowed aboard the jet. And I still smoked, so I enjoyed one cigarette’s worth of impossible luxury and freedom before stretching over an entire row of seats and settling into a deep vodka sleep that would last halfway around the globe.

***

Hungary was gray and cold, because it was wintertime and I had just voluntarily left the coast of Southern California for Central Europe. Cellphones were still rare and email a novelty. I wandered the dingy halls of the Budapest airport wondering if my friends knew my flight was late and also a completely different flight on another airline. And then I spotted a tall, lanky and very pale vampire of sorts with Nick Cave hair, waving and smiling at me. The American friends who got me hired for this job at an English-language business paper in Budapest had brought him along to the airport, so I worked through the crowd of Magyars and greeted these people who now held the reins of my existence.

The vampire was a refugee from the troubles in Kosovo and Serbia, stuck here in Hungary because the Austrians wouldn’t let him across the border. He was wildly enthusiastic about everything and had at least a dozen scams in the works, including benefit concerts for displaced Yugoslavs and a local Star Trek convention that would somehow get him dates with the six-foot-tall local women.

Samet, the Turkish-Albanian variation of the Islamic name Samed, was bunking at a youth hostel overrun with young people lacking the right visa to get somewhere else. He was also nearly broke and couldn’t legally get work in Hungary, so on the occasion of my Welcome To Town party, he was invited to join the three Americans in a dusty high-ceilinged apartment on Bartok Bela. Samet cleared out a monk-like cell where decades of broken furniture had been stuffed along with the unwanted heirlooms of whatever family owned this flat. I took a sofa in the immense main room with its three different living room sets. That was fine; I was always the last person awake.

Budapest was still an inexpensive city for an American, especially if that American had just collected various windfalls from unused vacation time, writing a couple of freelance chapters for one of those “For Dummies” computer books, and somehow selling two “story treatments” (single pages of occult nonsense) for a cable-TV revival of an old science-fiction anthology series “The Outer Limits.” I had something like four-thousand dollars in American Express travelers checks, enough to last at least a year if I didn’t go overboard with food and drink.

Eventually, after a lengthy round of parties and dinners and late nights of guitars and conversation, I had to report to my new job: technology columnist for the Budapest Business Journal. I knew little about the technology business and less about Hungary, but I was handy with “the Internet,” which was still baffling to newspaper people. (The technology seemed to come naturally to the young Hungarians working for the paper, and they would help make Budapest the 21st Century offshore IT capital of many U.S. new media businesses, including Gawker Media.) The office was on the second floor of a courtyard building a couple of tram stops from my apartment. It looked almost exactly like the computer-magazine office I’d just left in San Diego. My heart sank.

“We’ll probably put you here,” the managing editor said, pointing to somebody else’s portion of a work table crowded with press releases and copies of the Financial Times. He looked around to see if anyone would take care of this task, but everyone was either yelling in Hungarian on the phones or gazing intently at their monitors. The managing editor shrugged and got his overcoat. “I guess it’s time for lunch, anyway. Plus, you need to see the Chain Bar.”

The Chain Bar was a nearby lounge full of stout blue-collar workers in matching overalls and giant blonde prostitutes, a classic Disney scene of sorts. The jukebox played the theme from “The Rockford Files,” again and again. I missed my first, second and third Hungarian Lessons paid for by the newspaper before the receptionist stopped putting my name on the schedule. I excused this irresponsibility by remembering how hard I’d worked on Slovak a few years prior, and how I had yet to come across a need for knowing so much as a single word of the Slovakian tongue since leaving Bratislava. But the truth was and remains that I cannot learn foreign languages. For all the words and phrases I’ve collected, I have never surpassed the linguistic accomplishments of ordering dinner or figuring out the gist of a newspaper story (by looking at the picture).

Samet was a polyglot. No, he was a hyperpolyglot, fluent in English, Macedonian, Albanian, Turkish, German and both the Serbian and Croat variations of Serbo-Croatian. I believe he had learned classical Arabic from studying the Qur’an, and he apparently spoke nearly flawless Hungarian thanks to his few months stranded in the country. I needed to get out and report on things, because offices depress me, and Samet needed something to do with his time. We became a team, with my pay from the newspaper covering our rent and groceries at the apartment, and we covered trade shows.

***

There was a convention or technology fair every few days — technology was booming! — and these spectacles were just foreign enough to provide some material to potentially amuse MBAs from Chicago on the make in post-communist Central Europe. Urban Hungarians maintain a pagan appreciation of pure sexuality that has never been comfortable for most Americans. While barely dressed young women were commonly employed to sell video games at U.S. electronics shows, it would never occur to use astoundingly tall women in nothing but translucent panties and bras to sell accounting software. In Budapest, that was the norm. It was also common to find the bored models humping on their short, muscular boyfriends during lapses in business, under the cold fluorescent lights of whatever Trade Progress Hall, right next to the folding table with the branded ballpoint pens and logo stickers. Somewhere I still have a promotional mousepad handed to me by a model working an elaborate Microsoft booth: It was just a pornographic “double penetration” photograph with no conceptual ties to the local version of Excel that I could discern.

I can only assume that in the fifteen years since, the Hungarian technology sector has adopted the more prudish tech marketing habits of its international peers. It was pretty thin gruel for a weekly column, anyway, and during our long rides by taxi and tram to various industrial sectors and convention centers, Samet regaled me with tales of his hometown: Skopje, the charming capital of the new Macedonia and the only Yugoslav republic to reach independence without warfare. It was a land of opportunity. We could launch a radio station, a television station, even a feature-film production house. And so we decided to start all three, with my depleted packet of travelers checks as capital and Samet’s family home in Skopje as headquarters for this media empire.

It was already spring down there, 600 miles south on the green banks of the Vardar River, and we just needed to get through Serbia and Kosovo, which were just then beginning a war of their own. The Serbian military patrolling the trains would likely be unfriendly to an ethnic Albanian and an American traveling together without papers, but at least all the beer in our luggage was for me — Samet followed the Prophet’s ban on booze.

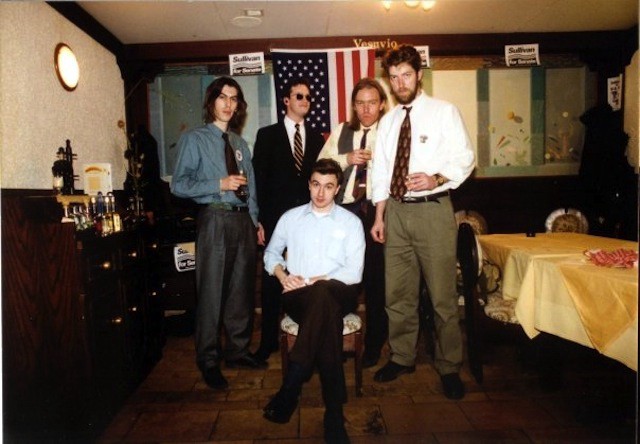

Samet, left, and the author, right, on the occasion of their colleague’s birthday and U.S. Senate campaign kickoff in Budapest. Photo by a waitress at Pinocchio’s Italian restaurant Jim Lowney.

Related: Life After Patch.com: A Newspaper Editor Returns To Newsprint

Ken Layne has held approximately a hundred media jobs around the world. He should’ve learned by now.

Top photo by Deannecow.