A Natural History Of The Penis: A Visit To Iceland's Infamous Penis Museum

by Ferris Jabr

If you haven’t heard of Sigurður Hjartarson by name, you’ve probably heard of his penis… museum. Hjartarson and his son Hjörtur Sigurðsson own and manage The Icelandic Phallological Museum in Reykjavik, which has the world’s largest collection of penises and related artifacts (283 and counting!). This winter I finally got the chance to visit, along with my good friend Mara. My first surprise was how sleek and modern it looked from the outside: large frosted windows with “The Icelandic Phallological Museum” printed in neat type in various languages, almost in the style of commemorative glass plaques. From a distance, one might mistake the building for an art gallery or office space, if not for the large silver sign that features what is perhaps the most forthright museum logo ever devised: a mushroom-capped penis standing at attention in front of a silhouette of Iceland.

Mara and I were the only visitors when we arrived. After paying 1,000 Icelandic krona (about 8 US dollars) each for our tickets, we walked past the front desk, turned a corner and entered the museum’s well-lit main room. We were surrounded. Penises and testicles claimed every available surface — sprouting from the floor, crowding shelves, hanging from the ceiling. One enormous brown phallus drooped from the wall like the schnozz of a Norwegian troll or something melting in a Salvador Dalí painting. Many penises were plump but limp in jars of formaldehyde, floating as contentedly as pickled turnips. A few were as stiff as stone, fixed in eternal erection. It was a quiet and dignified room demanding a kind of sedate reverence: all those specimens carefully arranged, waiting for the monosyllabic expressions of admiration and hushed conversations of passersby. It was, too, a room full of dicks.

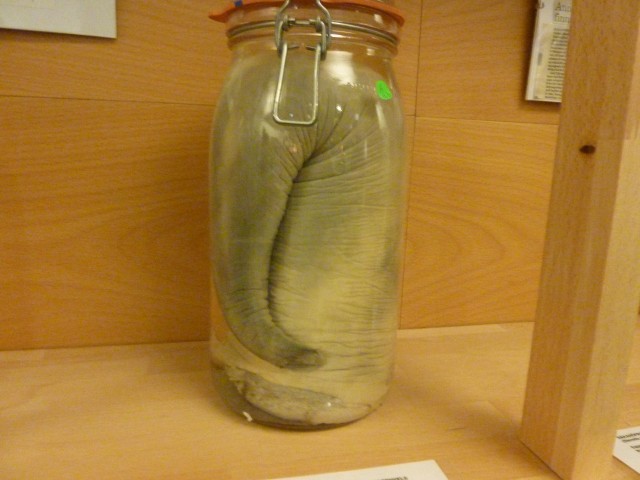

I stopped in place, overcome with a unique sense of awe. It reminded me of visiting Six Flags Great America for the first time with my middle-school friends: the sight of all the possibilities before us — the coasters’ colossal slopes, steep drops and gorgeous loop-de-loops — stunned us for a moment, before we bolted into the theme park. Now, older, I reacted more sensibly. Composing myself, I stepped into the room, readied my camera and casually turned toward one of the displays on my left. In a glass jar about four times larger than a standard jar of jam, a fat grey organ curled in on itself like an elephant’s trunk. Its slightly wrinkled skin pressed right up against the glass. I took a picture. A laminated piece of paper informed me that this was the penis of a sei whale, which is among the larger species.

In the museum’s marine mammals section.

(This photo and the one above courtesy of the Icelandic Phallological Museum.)

A sei whale penis in a jar.

In a refreshing contrast to many museums, the Icelandic Phallological Museum completely lacks any pretense or stuffiness. The museum is honest about its purpose: this is a place to come and marvel at a great many penises of different shapes and sizes. Compared to most natural history museums, however, it’s a little light on information. All the specimens are paired with pieces of paper listing the Latin and common names of the relevant animal, and the museum’s website has a thorough catalogue recording the provenance of all the penises in the collection. One of three nooks toward the back of the museum houses a small library. Beyond that, however, there are no panels, videos or exhibits to further stimulate guests. You must be your own guide through this wonderland of phalluses.

To my right, in a tank of clear fluid, rested what looked like an enormous rotting daikon root. A thin sleeve of soot-colored skin had peeled away in places, the way a potato’s skin starts to slip off if you boil it long enough. Next to the bulbous shaft sat a single testicle, which resembled an ostrich egg with a mozzarella texture. It used to sit cozy inside a sperm whale.

In a phone interview, Hjartarson told me that the museum boasts a penis from every kind of mammal now living in Iceland. Nearly half of the penises in the museum once belonged to sea mammals, such as whales, dolphins, seals and walruses, most of which were caught in the waters surrounding Iceland. Covered in glaciers, lava fields and deserts, the mainland is not exactly teeming with terrestrial wildlife. Iceland has no native amphibians or reptiles and fewer than 90 breeding bird species, the most famous of which is the adorable puffin, which looks like a hybrid of a penguin and toucan. When people first colonized the island, probably sometime in the 800s, the only native mammal was the Arctic fox. Today, Iceland is home to sheep, cows, goats, horses, dogs, cats, minks and mice among other mammals, all brought to the island by people in various deliberate and unintentional ways.

A few more exotic peckers have come to the museum as well, most of which are displayed in a nook known as the “foreign section.” Through friends, Hjartarson’s son Hjörtur Sigurðsson acquired the penis of a giraffe that was shot by an Icelander in Namibia in April 2012. In 2001, an Icelandic engineer sent Sigurðsson and Hjartarson the penis of an old male elephant gunned down near a sugarcane plantation in South Africa. In 1993, after some fishermen accidentally killed a cantankerous polar bear that had wandered from Greenland onto Iceland’s western fjords, a natural history museum got the skeleton — including the bear’s penis bone — but Hjartarson got the penis itself. “No animal was ever killed for me or because of me,” Hjartarson says.

AND THEN ONE DAY YOU WAKE UP OWNING A PENIS MUSEUM

An elephant penis, preserved.

Taking the life of an animal solely to acquire its reproductive organs would betray the spirit of the museum. The whole thing started as a joke among friends. In the 1970s, Hjartarson was the headmaster of a school in Akranes, a port town in southwest Iceland. One day, over drinks, he and some teachers got to talking about ancient Icelandic traditions — in particular the tendency to use every part of a slaughtered animal. The conversation surfaced a memory in Hjartarson’s mind: as a young boy, his relatives had given him a pizzle — a bull’s penis twisted and fashioned into a cattle whip. When Hjartarson related the memory, one of the teachers said that he was traveling to his hometown to help slaughter some bulls and offered — mostly in jest — to bring back their penises. Hjartarson thought it was a great idea.

At first, he was not sure what to do with his gifts. He tried hanging them out to dry like laundry. People in Akranes started talking; some neighbors mistook the penises swaying in the wind for rhubarb. Eventually Hjartarson decided to have a few of them tanned and others stretched and affixed to plaques, keeping them somewhat more discreetly in his home.

Not knowing much about preserving whale penises between three and eight feet long — or any penis for that matter — Hjartarson tinkered and learned along the way. Sometimes he split the penises open, scooped out everything inside and dried the peel with salt. He experimented with alcohol and formaldehyde.

Hjartarson soon began to receive similar, albeit much larger, gifts from other teachers who spent their summers working at a nearby whaling station. Not knowing much about preserving whale penises between three and eight feet long — or any penis for that matter — Hjartarson tinkered and learned along the way. Sometimes he split the penises open, scooped out everything inside and dried the peel with salt. He experimented with alcohol and formaldehyde. One time he tried filling a penis skin with silicone — a disastrous approach. The skin shrank and expanded when the temperature and humidity changed, but the silicone remained inert, bursting through the delicate membrane.

“The idea emerged gradually that it might be interesting to go on collecting these,” Hjartarson recalled. In addition to accepting donations, he started to actively pursue specimens. He turned to abattoirs for spare parts. He asked a friend in the fishing town of Húsavík to keep on ice the penises of any seals he caught. When he heard about a beached whale on the news, Hjartarson would join the team of scientists traveling to the stranding site and ask if he could take home the penis.

For twenty years, Hjartarson stuffed the swelling multitude of penises into his home and office, taking them with him when he left Akranes to teach in Reykjavik. In 1997, his daughter in law secured a retail space in the center of Reykjavik and, since the space was too large for her purposes alone, she and Hjartarson decided to share it. He knew exactly what he wanted to do with his half.

The same year, Hjartarson officially erected the Icelandic Phallological Museum with penises from 62 different species. “Most people reacted pretty positively,” he said. “When people see there is nothing pornographic in the museum, just these organs, and that we try to put some humor in it, people react very well.”

How did his wife react, I wondered. “She has been supporting me the whole time,” Hjartarson said. “Without her patience and tolerance I would never have been able to do it. I’ve taken specimens into the kitchen to work on them. Some have smelled like hell. She hasn’t liked that as much, but she has tolerated them incredibly.”

The Icelandic Phallological Museum has remained a family affair. When Hjartarson retired from teaching in 2004, he and his wife moved north to Húsavík and reestablished the museum there. In 2011, due to his poor health, Hjartarson passed on management of the museum to his son, Hjörtur, who moved it back to Reykjavik. Lately, Hjörtur Sigurðsson’s 23-year old son has been helping out in the museum as well. Since reopening in November 2011, the collection has attracted more than 13 thousand visitors.

NONE OF THESE PENISES IS LIKE THE OTHER

Sculptures of the Iceland men’s handball team.

At the end of a long row of sea mammal penises in jars, a piece of art caught my eye. The museum offers visitors plenty of interesting sculptures, paintings, carvings and tchotchkes to look at, including lampshades fashioned from bull’s testicles and a set of shiny silver penis sculptures, above which hangs a photograph of the Icelandic handball team. Hjartarson’s daughter, Thorgerdur Sigurdardottir, made the sculptures and, as she told Slate, they are not in fact modeled after the members of the Icelandic handball team; rather, she “made them from experience.”

The piece of art that I liked most, however, was a framed poster labeled “The Penises of the Animal Kingdom,” which featured a lineup of erect organs from various mammals, in order from longest (the whale’s) to the shortest depicted (man’s). The poster reflects what is perhaps the museum’s central theme: diversity.

Scientists have learned that the penis is an excellent organ to study precisely because of its diversity. Over the millennia, many different animals in many different environments have depended on their penises to fulfill one half of the most important mission for any living thing — reproduction. In response to this pressure, the penis has adopted an astonishing variety of forms. Penises first evolved in the ocean, where they pioneered a sexual strategy known as internal fertilization. Instead of spraying his sperm into the currents and hoping that some of them hooked up with a female’s deposited eggs — the way that many fish still go about it — a male animal with a penis could shoot his sperm directly at a female’s eggs while they were still inside her body. She, in turn, gained more control over which suitors had access to her eggs in the first place.

Modern penises come with all kinds of frills and accoutrements, like bristles, barbs, foreskins and multiple heads (some marsupials have forked penises; the echidna’s penis has four heads). Some penises engorge themselves with blood or lymph fluid; others rely on a mineral bone to get a boner (in fact, humans are one of the only primates without a penis bone).

Penises have evolved independently several different times in different groups of animals, often as modified forms of existing body parts, such as fins. In all likelihood, the earliest penises were relatively simple and undecorated tubes, perhaps resembling the stout shaft of the 425-million-year-old shrimp-like Colymbosathon ecplecticos — the oldest fossilized penis ever discovered. Some animals still rely on rather modest penises, but many others developed far more complex and ostentatious organs.

Modern penises come with all kinds of frills and accoutrements, like bristles, barbs, foreskins and multiple heads (some marsupials have forked penises; the echidna’s penis has four heads). Some penises engorge themselves with blood or lymph fluid; others rely on a mineral bone to get a boner (in fact, humans are one of the only primates without a penis bone). When erect, penises might be rather stiff and inflexible, or — as in the case of whales and dolphins — retain a rubbery agility. Some penises are unexpectedly small for an animal’s overall size, such as the gorilla’s typical nubbin (1.25 inches erect on average). Others are astoundingly large: the humble barnacle claims the longest penis relative to body size of any animal. A sedentary creature, the barnacle probes for a mate with its impressive penis, which can be eight times its own length .

The duck’s phallus is a particularly rousing example of extreme penis adaptation. 97 percent of bird species do not have penises. Ducks not only have penises — they have long, spiraling ones that burst forth from within their bodies. These elaborate phalluses most likely evolved through sexual conflict. Male ducks are notorious rapists. To combat these unwanted advances, the females have evolved labyrinthine vaginas that twist in the opposite direction of the males’ corkscrew penises. These vaginal passages are filled with spongy pockets with which the females might sop up and expel unwelcome sperm. In retaliation, the males evolved longer, larger and more tightly coiled penises. The penis of the Argentine Blue-bill duck, for example, can stretch to twice its body length when erect. Still, only three percent of duck rapes result in viable offspring.

PRESERVE YOUR PENIS, LIVE FOREVER

After getting a good look at most of the animal penises in the museum, I walked into the folklore section, where I encountered specimens from creatures that are complete strangers to science. According to surveys conducted over the years, between one quarter and one third of Icelanders currently believe in the existence of “hidden folk” and elves. Icelandic myths and legends include an even more varied cast of specters and ghouls. The museum’s folklore section, however, is not really concerned with telling these tales to visitors.

To get a sense of what this particular nook is like, imagine going to an exhibit about American tall tales and, instead of watching a heartening video about Paul Bunyan and his dear companion Babe the Blue Ox — or leafing through beautifully illustrated books about Davy Crockett and Johnny Appleseed — you encounter nothing but glass cases that display what are, ostensibly, these heroes’ penises. Somehow, the Icelandic Phallological museum has managed to acquire the kelp-green penis of a merman (wait, aren’t merfolk supposed to be all fish down there?), the pallid penis of a ghost, the penises of a zombie bull and corpse-eating cat, and an elf’s penis, which is, naturally, invisible.

A merman penis.

The specimen that would prove most elusive for Hjartarson had nothing to do with the mythological, though. By the mid-2000s, Hjartarson had acquired the foreskin of a 40-year-old Icelander, as well as a 55-year-old Icelander’s testicles and epididymis (a tightly coiled tubular passage for sperm that sits atop the testes like a wig of ramen noodles). But he still wanted a whole human penis, with its shaft, balls and all.

In 2006, an elderly Icelandic man — a proud womanizer, according to Hjartarson — signed a letter pledging to donate his entire penis to the museum when he died. He passed away in January 2011. His penis now sits at the bottom of a glass jar of formaldehyde, but it bears little resemblance to typical members of its kind. It is grey, lumpy, wrinkled and sparsely covered in wiry pubic hairs; its tip seems to end abruptly, like a severed tree branch grown rough and knotty over time; its back end is an open mess of flesh and fat.

Hjartarson blames himself for the specimen’s unfortunate state. “When they called me and asked me what to do with it, I think I was drunk,” he told me on the phone in a hushed voice. “I said just put it in formaldehyde. We should have put it in water or vinegar. I should have stretched it or sewed it a little at the back.” He thinks that such preparations would have better preserved the original shape of the penis. “But we can always get a better one, a younger one, a bigger one,” he added. Three other men have promised to give their penises to the museum when they die: Peter Christmann, a German; John Dower, an Englishman; and Tom Mitchell, a rather unique American.

On his personal website (NSFW), Mitchell explains that he has loved his allegedly enormous penis from a very early age and has long thought of it as a remarkable toy to be enjoyed as much as possible. Admittedly, that might not distinguish him from most men, but Mitchell’s confidence evolved in an unusual way. After his wife nicknamed his penis Elmo and began to treat it as a living creature, Mitchell realized that his penis was indeed a kind of alien being attached to his body. Now, Mitchell is determined to share Elmo with everyone. “I want you to adopt him as yours,” he says on his website, “and to accept him as if he’s been attached to your body instead of mine.” Mitchell has resolved to remove his penis while he is still living, plastinate it and donate it to the Icelandic Phallological Museum. In the meantime, he sent a plaster mold of his organ to reserve his space.

The collection Hjartarson started more than 40 years ago will surely keep growing for the foreseeable future, but it may never be complete. ‘Completeness’ is not a particularly applicable concept in this situation. Even if the museum managed to collect a specimen from every single penis-wagging species known to science, there would still be thousands, perhaps millions, of undocumented species out there. Even in the twenty-first century, scientists find relatively large animals that they have never seen before, such as the Myanmar snub-nosed monkey and a new kind of slow loris, discovered in 2010 and 2012 respectively.

One penis that might bring the collection full circle, though, still hangs between the legs of the man who conceived of the museum in the first place. His son is committed to contributing, but Hjartarson himself is less certain. “It depends on who dies first,” he said, “me or my wife. If she dies first, the museum will get the specimen. If I die first, I can’t guarantee it.”

Ferris Jabr is an associate editor at Scientific American and a freelance writer based in New York.