The Great, Forgotten Sci-Fi Novel About The End Of The World

by Maria Bustillos and David Roth

David Roth: So, tell me again, please, how you found this novel, The Last Western? I know how I found it, which was by you giving me a copy and telling me it was important that I read it.

David Roth: It was like Natalie Portman’s “The Shins will change your life” moment in Garden State, except you are shorter, smarter and less pointy than she is, and I am marginally less grumbly-sad than Zach Braff, and you were right and also The Shins couldn’t conceivably really change anyone’s life.

Maria Bustillos: A guy named Mark Harris went all crazy over it on this listserv I was on back in 2002, and he persuaded me. So I went and found a copy (not easy, it has been out of print since the 1970s) and had my wiglet blown sky-high. I was so happy you loved this book, David. This beautiful book about the end of the world.

Maria Bustillos: I want everyone to read it. So back in the day, I offered my copy to this listserv, and there was a monk in Klosterberg, Germany, who agreed to read it, his name is Erwin and he taught me even more and more about it, and he became one of my best friends.

David: How my friend Maria joined the Sacred Order of the Very 1970s Catholic Social Apocalypse/Baseball Novel. Given that only like 50 people alive have read this thing, we should probably run down what happens in it.

David: So: a child is born in a doomed outpost, in a time Very Much Like Our Own circa the shittiest Watergate low ebb of everything. He moves to a more-doomed Houston. Develops an unhittable rising fastball and makes it to the Bigs, just like Byung-Hyun Kim did. Leaves the league because of some complicated metaphysical reasons, unlike the way Byung-Hyun Kim did. Houston is levelled by riots. Our hero joins a secretive monastic order. Becomes a priest, is assigned by the Vatican to the rioting inner cities… we are not yet halfway through.

David: But it’s not all that sprawling, considering. It covers a lot of ground and time, but it stays centered on Willie, our Christ-ly hero with the 8-grade fastball.

Maria: All this is TRUE but doesn’t actually touch what’s being said, which has the subtext: how is a just man to live in an unjust world?

David: Right. Which is a pretty ambitious question for any novel. And which Klise decidedly does NOT make any easier for himself.

Maria: Continuing: Willie has a relationship with a more worldly boy, Clio, who understands him but is frustrated because saints can’t be real people: protect yourself, he is saying. Kind of like Anne Hathaway telling Batman, “Let’s get out of here.” But it’s not like the world is safe for anyone.

Maria: The style of it is very curious, simultaneously the most naive style you’ve ever seen, and the most sophisticated one. Klise is a very undeceived writer; this thing goes to the fucking mat, page after page. Not even Thomas Mann was this brutal. But it’s science fiction, too. The cover blurbs are from like Philip Jose Farmer.

David: Such great 1970s cover blurbs. Weird journals that don’t exist anymore.

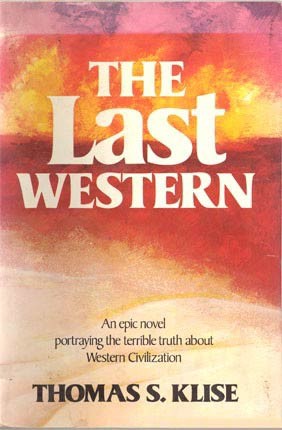

Maria: The cover, too, is perfect.

David: Some guy from Commonweal saying “Thomas S. Klise, you have written more than a novel, you have written a revolution… This may be a turning point in American literature, if it is not the final climax.” So an A-minus overall, then, presumably?

David: There’s something amazing about a book this spectacularly distinctive, strange and good becoming this obscure, though.

Maria: The author died really young; that’s part of it.

Some guy from Commonweal saying “Thomas S. Klise, you have written more than a novel, you have written a revolution… This may be a turning point in American literature, if it is not the final climax.” So an A-minus overall, then, presumably?

David: It’s not un-flawed, obviously. It’s VERY STRANGE and very 1970s in the sense, shape and scope of its doominess. But it has disappeared utterly. Thomas S. Klise doesn’t have a Wikipedia page.

Maria: Plus it’s also HILARIOUS, which I can’t even fathom how he manages that.

David: It’s his only novel.

Maria: Alas!

David: And a new copy will run you $245 on Amazon (although there are some used ones for more like $35)

Maria: There are only fifteen copies on ABE just now. Full disclosure, I am inflating the price single-handedly, I’m afraid… every time I see one under $20 I buy it and give it to some deserving soul.

David: Maria Bustillos stays moving markets.

David: And for all the romance of an actual classic that’s so utterly disappeared, the book really does deserve that sort of treatment. It would if it somehow wound up back in print (ahem), too.

Maria: Here is a passage for our readers to try. Very hard to choose. It’s a discrete experience, unbreakable, so this is like telling one moment from a long dream. But here the mute pilot Truman shares the story of his life, in signs, with our hero.

His first signs portrayed childhood — growing up in a large city.

Happy father. Happy mother. The father goes away. A uniform of some sort. The father flying. The mother and son together.

Then sadness. Something happening to the father. Hurt. In jail.

Joy. Great unexpected happiness. Father comes back.

But not joy after all. Something has happened to father.

Now moving away. Father and mother and boy going somewhere. Many somewheres.

Flying.

The Man of Sorrows made airplane movements with his hands — strange, dangerous, wild movements.

“Stunt flying — for a carnival,” Father Benjamin whispered.

The strange dangerous flight gestures continued. Then — smack! The airplane had plunged into the ground. Father dead.

Pause.

Now the mother and son moving again. Something about a name. Something has changed.

Willie strained to see the signs the Man of Sorrows made.

The mother has gone now. More flying.

This time, he, the Man of Sorrows, is flying

Stunt flying.

Pictures. Something to do with movies.

Then more flying. Flying to other countries. Some kind of flying mission. Flying food — no, blood — somewhere.

A place of war.

Maria: So my friend who is very very well-read and who was a monk at that time and is consequently super-conversant with Catholic literature said this about the book: “What I found ambiguous in this context was the continuous ‘deep’ rage and desperation of the tone, which sometimes felt like a pose, and with time started to get on my nerves, and also reminded me of a former flatmate who was a Dead Kennedys fan. I found it horribly ‘Seventies’ in its ‘naive’ and essential cultural criticism […] with conformist clothing styles representing reactionary world views (men in dark suits with black sunglasses) […] But perhaps naivete and essential cultural criticism aren’t such bad things after all, at some point in my life I even entered a monastery, so what am I talking.

What I found truly unctuous was the juxtaposition of Europe as cultivated and decadent (the comments on the art in St. Peter) and America as down-to-earth, ultra-capitalist but also the home of the naive and righteous. […] In this respect it tells much about ‘the’ North American self-image (sorry for generalizations of this sort; almost all Americans I got acquainted with in Germany spent most of their energy in being embarrassed by being Americans, especially when there are others within sight, while at the same time finding everything worse than in America; self-referential paradox again).”

This, by way of explaining the kinds of things you will be thinking about when you read the book.

David: That’s a wise monk. And all the doomed-ness is heavy; overstatement is everywhere. It doesn’t exactly duck parody. And yet there’s this sense of command, broadly.

Maria: It’s funny and it is supposed to hurt. And it does, a lot. Hurts like Kafka, or worse even.

David: But the book is also in this weird tone of high-volume satire/parody.

David: There’s a George Saunders-y overstatement to a lot of it; some of the images — the weird Martha Washington doll for kids that has different moods and burbles little weird patriotic aphorisms, for instance — are just hugely Saunders-ian.

Maria: The Saunders comparison is apt. We MUST send him a copy, I wonder if he has heard of it?

David: A lot of it has that Saunders feel, the heightened unreality and the very real and very despairing critique in the same weird space. This generalized disgust with crass marketplace things taking some very specific and very weird shapes. The difference, for me, is that Saunders’ disgust is with a world I recognize a good deal better than this one. Our materialism is obviously state of the art relative to the 1970s, awful as I’m sure it was then; I wasn’t alive, but I have seen Nashville (LADIES). But that Nixon-era sense of apocalypse-by-the-end-of-the-week is foreign to me. But it’s urgent enough that it still works, even as the book dials up the overstatement.

Maria: Holy moly this is one of the rare times I feel the generational divide between us, David. I think things are a good deal scarier now.

David: Oh, I would never say that things aren’t scary as shit. Let me get on the record with that: everything is fucked and feels very fucked. Go on.

Maria: What with the stone fact that the planet won’t support an Indian middle class, let alone a Chinese one, at the current rate of emissions. And our politics are so pathetic, like trying to move the Himalayas with a teaspoon.

David: Well, yes. So many things creeping upwards, in some cases very quickly. But the mood of the big pieces of art from the 70s — and I’d put this up there, with something like Apocalypse Now — reflect a very violent, very urgent and very specific sort of gloom that feels sort of foreign, now.

Maria: Hmm, that is true.

David: We play with it, now. Batman is “dark,” for instance, but it’s mostly a game. There are people who take it very seriously, I guess, and I like the movies fine, but that’s not a worldview, necessarily. It’s a half-reasoned gloom-o edginess in a movie with a billion dollars behind it.

Maria: You have like Houellebecq, too, kind of similarly, there’s a bleak view of individuals more than of the whole human project. Maybe we are so scared now of the world really ending that we are too scared to talk about it.

David: And Houellebecq has that willingness to go big and get weird. He doesn’t necessarily mind blowing up a bunch of people to make a point.

Maria: I love that about him. So creepy, but I love it.

This shocking rewriting of history, for entertainment. Let’s imagine it the way it ought to have been! There is something giddy about it, sunshiny and horror-striking at once. Where Klise is saying, by golly, those fast-approaching clouds are black.

David: But that’s not where novels really are, now. There’s a retreat to the human scale — which is broadly good, although not necessarily less grandiose if, say, Jonathan Franzen is doing it. And then there’s this abstract-o magical mystery tour upper-middle-class self-actualization fantasia thing.

Maria: Inglourious Basterds, I was going to say, is kind of the anti-Klise.

David: How so?

Maria: This shocking rewriting of history, for entertainment. Let’s imagine it the way it ought to have been! There is something giddy about it, sunshiny and horror-striking at once. Where Klise is saying, by golly, those fast-approaching clouds are black. And they are real. And they are coming.

David: As much of its time as it is, though, I don’t think The Last Western is quite an artifact. Or just an artifact. If only because of the way that our current brand of awfulness — The Way We Suck Now — sort of echoes the 1970s. We just have much more advanced phones.

Maria: Beyond that, even. Mark Harris thought that Klise might have had trouble selling the book because of its religious (or, if you like, anti-religious) themes.

Maria: But for this reader the utter fearlessness, the strange naivety, with which the author engages bedrock moral questions is unsettling in exactly the way that we need, and that is seemingly absent from our fiction now.

David: Except for George Saunders, who’s a lot more Buddhist than Klise, I think that’s right. And it’s not like these are settled issues. No one was like, “we’ve figured out how to be good in a bad world, so let’s try to figure out what makes rich white folks’ marriages fall apart.”

David: What’s striking is that, among the How Can We Live writers doing that sort of thing now (and Saunders is my favorite, but there are others), Klise is actually fairly explicit and non-abstract in how he faces that question down. And this is a guy who wrote a book about an illiterate kid who throws a fastball with a lot of late movement and who later becomes THE POPE.

Maria: Right? Which sounds like Terry Southern BUT MAN, IT AIN’T.

David: Yeah, this is awfully rough and despairing for satire.

Maria: The pea of moral seriousness under the various shells of satire. But with Klise you lift every shell and there is a pea under each one. It’s unnerving.

I guess I would add that today’s despairing fictionalist isn’t grabbing the reader by the throat and demanding not only that he confront his own complicity but that he change his ways, this instant.

David: Maybe what grounds it, or keeps it from floating into the sort of meta-satirical space of its more contemporary near-counterparts, is that Klise doesn’t really fuck with mass media. The movie-related aspects of the book — and we’d be spoiler-ing to go too far into this — seem more to do with authorial meta-issues than any indictment of how that particular business shows us things.

Maria: I agree. Here is some period-specific comedy that reminds me a little of Klise’s attitude toward the absurdity of the Catholic institution.

David: So, you know more about all the Christian stuff (that is: you are not Jewish) than I. Just how heretical is this book?

Maria: Oh, completely. It’s a complete indictment of the Church as the repository of Christ’s teaching. Mind you, this kind of soul-searching is part of the liberal wing of Catholic teaching. You have a left and right, Vat II and like, anti-Vat-II. But Klise is scathing about Church’s elemental betrayal of the things Jesus advised. Trying to care for the poor, end war and so on.

David: But not at all really heretical about the teachings. The book is frankly very Christian and reverent, actually, about those.

Maria: Kind of? I don’t even know really about reverence for the Gospel, though. More like, reverence for the excellence (or necessity) of these ideas that Jesus had: take care of poor people, end war, try to figure out how to be good. Though I believe Klise was a practicing Catholic.

David: And this is maybe me being the age I am, but all that fussing and fuming and for lack of a better word caring about the church seemed sort of dated to me, too.

Maria: I asked my monk friend about all that back when I first got to know him. I said something like: How does someone like you (practically the most serious and intelligent person I’ve ever met, loves the Psychedelic Furs, and plays the piano like an angel; turned me on to Žižek and Theweleit, explained all these things about Foucault) — how do you manage this? With all the trouble in the Church, how do you manage it?

Maria: And he responded with something like: The standard answer is that the Church is a heavy burden on the weak shoulders of men, in short kind of like, “we are bound to fuck it up, like we do everything.”

David: Not at all a dated sentiment. We just keep that shit current every day.

Maria: Yeah. So do you think the world is going to end, David?

David: I’m of two minds on the apocalypse.

David: (I just wanted to type that.) I certainly have a difficult time, looking at the things that are wrong and the responses they’re engendering, feeling too optimistic about solutions. The abstraction and the deep and dimly understood grievances and the distance, all these different types of retreat: those are a bummer both because they give us a shitty discourse and stupid art, but also because problems as big as ours require non-individuated solutions, and a basic recognition that other people are as important as we are, and that we all ought to be thinking about each other a bit more. And working on that. Current events and all.

David: But on the other hand: we’re still here. People can be great. And the alternative to not fixing things is not tenable. The status quo is not tenable. People seem to be realizing this.

David: It’s difficult not to. I just can’t see how that translates, or what it translates into.

Maria: Well, here we are, agreeing about that, so there is a chance; where two or twenty or two thousand can agree, so can multitudes. Sometimes I fancy I can almost feel the change coming. I do not believe the world will end anytime soon, in part because it’s been ending my whole life. There are always surprises, fair and foul. Things are dire, certainly, but I have what I am going to have to call faith.

David: It’s something. There are, at least, still good books to read that haven’t been read before. So: work to do, then.

Before the end of the world hits, you might also enjoy reading: The NASA Scientist Who Answers Your 2012 Apocalypse Emails

Or re: Saunders: The Joys Of The George Saunders Style Sheet

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.

David Roth writes “The Mercy Rule” column at Vice, co-writes the Wall Street Journal’s Daily Fix, and is one of the founders of The Classical. He also has his own little website. And he tweets inanities!