Talking to the Dead: Channeling William James in Berlin

by Jessa Crispin

The second in a pair of essays today on being an expat in Berlin.

“Here is the real core of the religious problem:

Help!

H e l p !”

— William James,

Varieties of Religious Experience

“You’re in Berlin because you feel like a failure.”

I had met this man all of ten minutes ago and he had already summed me up neatly. I made subtle readjustments to my clothing, as if it had been a wayward bra strap or an upwardly mobile hemline that had given me away. More likely it was my blank stare in response to his question, “So, what brings you to Berlin?”

He has had to do this a lot, I imagine: greet lost boys and girls, still wild with jet lag, still unsure how to make ourselves look less obviously what we are, we members of the Third Great Wave of American Expatriation to Berlin. This man before me was second on the list of names that everyone gets from worried friends when resettling overseas. This is Everyone I Know in the City to Which You are Moving (Not Totally Vouched For). I lasted about a week before I sent emails tinged with panic to everyone on my list. He was the first to answer.

I must have blushed at the accuracy of the remark, because he immediately qualified it. “Everyone who moves to Berlin feels like a failure. That’s why we’re here. You’ll have good company.” Still embarrassed, I scanned the menu for one of the four German words I had mastered and, failing, pointed helplessly to a random item when the waiter returned. It would prove to be a strange Swiss soda of indeterminate flavor. It tasted like the branch of a tree, carbonated. It was not unpleasant. I had been shooting for something alcoholic, but I was already too laid bare to have admitting to a mistake and asking for help left in me.

At this moment it seemed unlikely this man could commiserate. My own failings were too grandiose, the depths to which I had fallen too abysmal. I was narcissistic in my failings, and he looked like he was doing pretty okay. He sat across from me confident, knowledgeable. He had ordered in German. The people in the restaurant had greeted him by name. He talked about artistic projects he was working on. He was certainly sweating less than I was on this hot July day. Later, a tale would unravel, one that mimicked the stories of so many of the Americans who flocked here over the last decade. Unable to survive financially in New York without having to abandon their writing, their art, their music, they came to a city of cheap rents, national health insurance, and plentiful bartending jobs that could cover their reasonable cost of living. He had an apartment. It had hardwood floors. A failure, my eye.

In contrast, there I was, ten days into my new city and still visibly shaken. I was tired of being the person I was on an almost atomic level. I longed to be disassembled, for the chemical bonds holding me together to weaken and for bits of me to dissolve slowly into the atmosphere. It was not a death-wish, not really. I was hoping something in the environment, some sturdier, more German atoms, would replace them.

Because there does seem to be something about Berlin that calls out to the exhausted, the broke, the uninsurable with pre-existing mental health disorders, the artistically spent, those trapped in the waning of careers, of inspiration, of family relations and of ambition. To all those whose anxiety dreams play out as trying to steer a careening car while trapped in the back seat, come to us. We have a cafe culture and surprisingly affordable rents. Come to us, and you can finish out your collapse among people who understand.

***

Let’s say, for a moment, that the character of a city has an effect on its inhabitants, and that it sets the frequency on which it calls out to the migratory. People who are tuned a certain way will heed the call almost without knowing why. Thinking that they’ve chosen this city, they’ll never know that the city chose them. Let’s say, for a moment, that the literal situation of a city can leak out into the metaphorical realm. That the city is the vessel and we are all merely beings of differing viscosity, slowly taking on the shape of that into which we are poured.

If that were the case, what to make of the fact that Berlin is built on sand? Situated on a plain with no natural defences, no major river, no wealth of any particular resource, it’s a city that should not exist. It can’t be any wonder that Berlin has, for hundreds of years, no, longer than that, past Napoleon, past the medieval days when suspected witches were lined up at the city gates and molten metal was poured between their clenched teeth, past the whispers of the Romans that whoever inhabited these lands were not quite human, back to the days when the people resided here are now only known to us by some pottery shards and bronze tools, always been a little unstable. It would explain the city’s endless need to collapse and rebuild, even as the nation that engulfs it marches on confidently, linearly.

Perhaps its unstable nature is what beckons the unstable to its gates. The Lausitzer. The Jastorf. The Semnonen. The nameless and the pre-literate. A shifting bunch of conquerors and the conquered. On through invaders and defenders, and populations reduced by half in war, disease, and the destruction of whoever pulled the short straw for being the scapegoat this century. The process merely sped itself up in the 20th century, oscillating madly through world wars and grotesque ideas, crashing economies and blind eyes turned.

It plays out seasonally as well, here in the northern reaches of Germany. The lush highs of summer, everything green and tangled with a sun reluctant to leave its post at night and overly enthusiastically trying to rouse you from bed in the very early hours of the morning, crashes almost endlessly down towards the darkness of the winter solstice. As the trees that had been blooming in a state of fecund glory when I arrived in the city lost their leaves, they revealed that the only thing that lay behind them was the endless concrete boxes of Soviet mid-century “architecture.” The sun shunned us, and rarely peeked out behind its thick cloud cover. When it deigned to, it gave off all the glow and heat of a porch light. The grey of the sky matched the grey of the buildings matched the grey of the thick coating of ice that remained on the sidewalks all winter. I fell on it one night, or early one morning, I guess, a little worse for wear, accompanied by a man I met at a bar, whose entire seduction strategy was just to follow me home, despite the fact that I kept trying to shoo him away like a stray dog.

I was six months into my Berlin residence. And from my akimbo position I threw the holy tantrum of a sailor-mouthed two year old. “Fuck this city. Fuck it. Why the fuck did I ever move here, god fucking damn it.”

“You’re strange,” said the German man, still resolutely standing by.

“Help me up.”

***

That’s when I took my William James essays off the shelf. I found in his works of philosophy a friend, a mentor, a professor, and some sort of idealized father. It was his works on the more mundane matters I relied on — how to make changes in your life, how to believe you can make changes in your life, how to convince yourself to get out of bed in the morning, how not to be a worthless slug — rather than his more important pieces about war or whatever.

James is now a bit of an odd fellow in philosophy. More widely influential than widely known, his theory of pragmatism and his groundbreaking work in the field of psychology makes him something of a hidden mover. If you do seek him out, it’s not generally in the way one reads Descartes or Kant or Nietzsche, as a refinement of the intellect or in the pursuit of one’s studies. One finds James when one needs him. He makes quiet sense of the world, in all its glories and deprivations, its calamities and its beauties. As a philosopher, James is able to hold all of the sorrow and violence and pain of the world in his mind and remain somehow optimistic. It doesn’t wipe out the goodness of the world, it just sits beside it. It’s no wonder then that people get a little religious about this agnostic philosopher, this man who can restore your faith in the world, without necessarily bringing god into it.

I sought out William James because I needed him. He and I were now separated by about a century of death, but we found ourselves occupying the same biographical eddy: bottoming out in Berlin.

***

Here is how William James found himself in Berlin: a failure. He had tried and failed to become a painter, failed to become a doctor, failed to become an adventurer. He was not yet a writer, but he was almost certainly still a virgin. He was in his mid-20s and painfully aware that he had failed even in deciding what it is he wanted to do. He stood there, absolutely calcified with indecision and doubt, while his soon-to-be-famous friends like Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. made decisions and started careers, and his soon-to-be-famous younger brother Henry started his literary apprenticeship with The Atlantic.

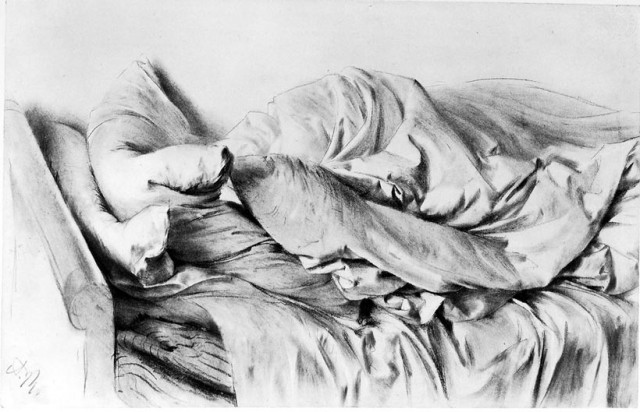

Whereas he — well, he fled. First to Dresden and then pulled to Berlin. He arrived under the pretext of furthering his education, but that may have simply been a way to convince his parents to pay for the trip because, despite his advancing age, he had yet to make an income. At any rate, he failed to go to class ever. Instead he holed up in his Berlin guesthouse, learning German, training his telescope on the legs of the occupants of the all girls’ school across the street, and failing to figure out a way to flirt with the attractive woman who played the piano downstairs. All the while he was alluding in his letters to his brother to a daily battle not to do himself in.

James lightly fictionalized this time in his life in his later work Varieties of Religious Experience, passing off the breakdown to someone he knows who told him about it. He’s French, you don’t know him. In that work he described the sensation of his suicidal idyll as “desperation absolute and complete, the whole universe coagulating about the sufferer into a material of overwhelming horror, surrounding him without opening or end. Not the conception or intellectual perception of evil, but the grisly blood-freezing heart-palsying sensation of it close upon one, and no other conception or sensation able to live for a moment in its presence.” And while his letters home hint at some of this darkness, mostly he chats to his parents about that other Berlin experience, the roast veal and the beer and the music and the philosophy.

Here is how Berlin responded to William James’ time in Berlin: they built a center in his name. At the place of his greatest misery and torment, they built a permanent structure.

Here is how Berlin responded to William James’ time in Berlin: they built a center in his name. At the place of his greatest misery and torment, they built a permanent structure. Although maybe at this point they can’t help it. After all the documentation they had to do of the horrors of the 20th century, maybe now it’s an unconscious reflex to throw up a memorial on the site of every trauma.

Or, not really a structure, I guess. More like a small room. The minute I learned of the center’s existence, I sent off an email making an appointment. I expected a building on the university campus, maybe in that glorious red brick so many of the buildings in James’ time had been built in. I scribbled the address down on a piece of paper and I took the train to the outskirts, to the University of Potsdam campus. It’s situated next to Sanssouci and its gardens, the former playground of the Prussian king. While the main path of the gardens is still marked with magnificent elm trees, most of it has been allowed to go to seed. It’s not a destination like Versailles, and so is kept in middling shape. There is a lovely rose garden, but that is surrounded by tangle and bramble. It’s been let go in the Berlin way, all of those straight German lines blurring a little into chaos.

Past the garden gates, into the campus, into the main philosophy hall, up the main staircase, down a hallway, to the left and then a right I came to my destination. It was a small door. The William James Center proved, despite its name, to be the work of only one man. Herr Doktor Professor Logi Gunnarsson. Or is it Herr Professor Doktor… I should have remembered to look up the proper order before I left. “It’s Logi, call me Logi.” Luckily Dr. Logi is Icelandic and not beholden to the German titling system. The center’s archives are really just the contents of Dr. Logi’s office. A desk, a computer, some bookcases. Dr. Logi is slight and sandy, and he has the wonderful awkwardness that comes with too many hours spent in the company of dead men.

He is, he tells me, as part of his administration of the Center, attempting to recreate William James’ personal library, so that he can be surrounded by the same books that surrounded James. It’s a devotional act, couched in a scholarly one. It’s an act I can understand. Dr. Logi pours me a cup of tea and we sit around chatting about our good friend William James. Up for discussion, a traumatic encounter with a prostitute, alluded to in letters to his brother and journal. He did, it seems, either lose his virginity to the prostitute or, perhaps even more traumatically, fail to.

“The poor dear,” I say.

“Yes, quite. He was hopeless with women. It seems, though, that after he married Alice Howe Gibbens, the physical ailments he was treating in Berlin, the bad back and so on, disappeared.”

“Were they caused by the burden of a protracted virginity?”

“Perhaps. The poor dear.”

I am keeping Dr. Logi from professional duties, but I don’t care and it appears he doesn’t either. I imagine it might be a relief for him, as it is for me, to have someone to converse with about our favorite person. Or willingly converse, as I’m sure he inflicts William James on the people around him like I do.

“What do you make,” I ask slowly, “of the fact that his first book was not published until he was 49?”

Part of William’s freakout, Dr. Logi had mentioned earlier, sprang from an enormous need to be seen. By the public, by his friends, by his father. He wanted to “assert his reality” on the world, as he wrote in his letters, and he had approximately twenty years after writing that statement until he would.

“Surely not…” Dr. Logi starts, but then he does the math in his head. “I guess I knew that but had forgotten. I mean… And he could not have known he would eventually succeed.”

We both sit quietly, drinking the dregs of our tea and feeling the long expanse of the years before us. The weight of uncertainty. Whether it’ll be a late blooming or whether the soil will prove to be infertile.

***

Whenever James was corresponding with a colleague or a querent, Dr. Logi told me, he would request from them a portrait. It was very important for him to see the whole of the person, at least a bit of their humanity, and not only their written representation.

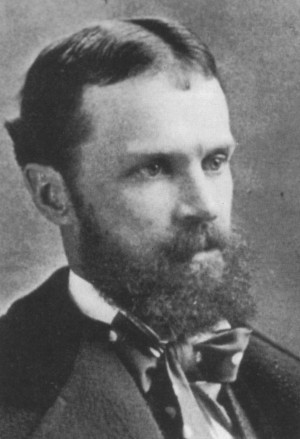

In that spirit, I have before me two images of William James. The first was taken around the time he moved to Berlin. He looks stricken. Pale and withdrawn, it is as if he had recoiled into a permanent flinch. He looks off to the side, unable perhaps to meet the camera’s gaze. There is something fractured deep at the heart of him.

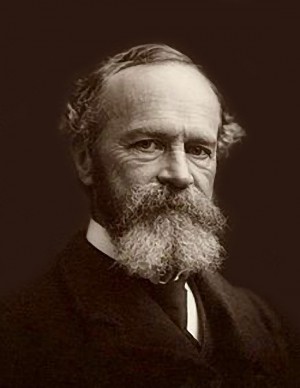

In the other, it is a few decades on. There is grey in his beard and his face is worn. He exudes charm, warmth, and wisdom. It is a William James in whose lap you would like to sit and listen to stories. He is keeping some secrets, but he will share them if you draw near.

It is the distance between these two photographs that is so fascinating. Not simply in age but in substance of the man. Biographers are interested (I am interested) in the Berlin breakdown because of the distance traveled between the two Jameses and the quality of the end result. It’s a favorite myth in our culture that hardship makes you a better person, that it is merely the grindstone on which your essence is refined and polished. But the truth is that scarcity, depression, thwarted ambition, and suffering most often leaves the person a little twisted. That is the territory where mean drunks and tyrannical bastards come from.

Not so with James. He may have always been a little hopeless with women (he sent a series of hilarious and heartbreaking letters to his Alice in the months before their wedding that will be instantly recognizable to anyone who has ever gotten a little sullen after a bottle of wine and decided to start texting) and the weight of depression did occasionally re-descend, but he walked out of that phase with dignity and great compassion. He used his experiences, both the good and the ill, for the base of his incredibly humane body of work.

So then what’s the magic formula? Can his transition be distilled down to a scientific equation to be reproduced at home in your own basement laboratory? Could we use William James’s example to turn our respective chemical imbalances into alchemical processes?

***

“There are persons whose existence is little more than a series of zig-zags, as now one tendency and now another gets the upper hand. Their spirit wars with their flesh, they wish for incompatibles. Wayward impulses interrupt their most deliberate plans, and their lives are one long drama of repentance and an effort to repair misdemeanors and mistakes.”

— William James, Varieties of Religious Experience

It is difficult to imagine the Berlin James would have encountered in the 19th century. So much of the city was reduced to rubble and ash in the intervening years. I can look at photos and get a sense of who the city might have been. But when I’m out, actually walking around on the streets, it is like an entirely different place.

Most of the surface of the city was scraped clean after World War II and the unsalvageable and the unclaimed was dumped in Grunewald on the outskirts of town. The pile of junk that used to be houses, used to be bakeries and hat shops, used to be attached to human bodies, was covered in dirt and the wild was allowed to reclaim it. Now it is something of a park or a nature preserve, with hiking trails through the woods — the trees still looking suspiciously young — up and down this artificial hill. One of the only hills in this swamp turned into a city.

The Germans may look like proper church-going Lutherans on the outside, but they are all at heart tree-worshipping animists from way back. Starting with the pagan cults in the Schwarzwald to the nature idolatry of the Romantic and counter-Enlightenment movements in the 19th century. It still bleeds through in their songs and in their art. A few decades before James arrived, Bogumil Goltz wrote, “What the evil over-clever, insipid, bright cold world encumbers and complicates, the wood-green mysterious, enchanted, dark, culture-renouncing but true to the law of nature must free and make good again.”

So maybe that is where James’s Berlin still resides, out in Grunewald, buried in some sort of purification rite inspired by a mysterious calling from deep within the German DNA. The wood-green making all of those horrors good again. It’s a calm place, soothing. But also policed by territorial wild boar.

***

Stefan is giving me important life advice over cocktails. I should be taking notes. Stefan is building an opera house, or I guess, overseeing the building of an opera house, and that seems like the type of person you should take seriously. He has in front of him a small glass of one of these Deutsch herbal liqueurs. It is the color of liquid garnets and it tastes like a potion. I am drinking a French 75, which I will retroactively feel shameful about later, after I learn it was not actually, as I believed, named after a spectacularly good year, but takes its name from a French cannon, the weapon used against the Germans in World War I. I wonder if this is why, in this Berlin bar, it is served strangely tinted red.

The bar is from the 20s, all dark wood and red wallpaper, heavy drapes and cigarette smoke. The experience of the place is heightened if you take the shortcut there through the courtyard of some residential buildings. It looks like a dead end on Google Maps, but you can weave your way through. You can go the long way around and stay on well-lit commercial streets, but then it no longer feels like a secret. Outside the bar is a poster for a performance of Cabaret — a German version of an American man’s musical version of a British man’s version of Weimar Berlin. Bob Fosse remains the link between my previous home of Chicago and my new.

I have trouble listening when Stefan is speaking, and not only because the bar tonight is loud and overcrowded, which it is. There is an army of white boys at the bar, drinking beer and wearing an almost identical uniform of trainers, jeans, and dark grey hoodie. I am keeping my eye on them. My real problem is that Stefan’s hair is so beautiful, so silvered and swooshing and glorious, that I find I have to sit on my hands to keep from forcing them into his mane. Shit, what’s that he’s saying?

“Don’t end up like Bertolt Brecht.”

That seems like horrible advice. Shouldn’t the goal of life be to end up as close to Bertolt Brecht as possible? I need a little context to his statement.

“When Brecht moved to Los Angeles he had such a difficult time learning English that he gave up. It soured him, being unable to communicate, and he started to hate America. Read his journals, you’ll see.”

For Stefan, every topic of conversation circles back to Bertolt Brecht, the way for me every topic of conversation circles back to William James. I take his point, which is made in impeccable English, shaming me further. I have been stubborn about learning to speak German. It feeds into my unsettled state. Why learn German if I’m only going to be here for a few years, but then how could I know if I wanted to stay unless I assimilate a little and give the place a chance? It is mortifying when someone addresses me in German I can’t follow, and yet part of me likes the little bubble I live in, the way I can tune out conversations on the subway because I can’t follow them anyway.

“Read Brecht’s journals,” Stefan repeats. “And learn German.”

***

I do read Brecht’s journals — translated into English. When he does write about America, it’s occasionally to complain about the FBI coming around to talk to him, and I wonder if that had as much of an impact on his displeasure with the country as his difficulty learning the language.

On March 23, 1942, he wrote:

remarkable how in this place a universally depraving, cheap prettiness prevents people from living in a halfway cultivated fashion, ie living with dignity. in my garden-house in utting, and even under my danish thatched roof, it was possible to browse over the bellum gallicum in the morning, here it would be utter snobbery. lidingö saw the discussions of the 20 on the mistakes made in spain, a few discussions with ljungdal on hegel’s dialectics, the young workers’ little masked theatre which performed HOW MUCH IS YOUR IRON? finland had marlebäk with the birch coppice round the house, the coffee hour in the main farmhouse after a sauna, and the two-room flat in the harbour quarter of helsinki, packed with good people. there was room for diderot and the epigrams of meleagros as well as marx. here you feel like francis of assisi in an aquarium, lenin in the prater (or at the munich oktoberfest), a chrysanthemum in a coalmine or a sausage in a greenhouse. the country is quite big enough to squeeze all other countries out of one’s memory. one could write dramas if it didn’t itself have any or need any, but it has all that, if in the most negligible condition. mercantilism produces everything, but in the form of saleable goods, so here art is ashamed of its usefulness, but not of its exchange value.

It reminds me of the inevitable line of complaint you hear whenever a group of American expats gather in Berlin. About the invasive nosiness of the Germans, about the way the pinched old lady who lives upstairs is always watching you and probably taking notes, about the way Germans stare at you on the street, on the subway, even in the saunas which will be of course both naked and co-ed, the way they don’t respect your personal space, the way grocery stores are closed on Sundays because the government at some point decided they’d rather women be at home with their families that day and now you can’t buy milk when you need it, the way they scold you publicly if you cross the street against the light, the way if you go to the pharmacy to buy antacids you are more likely to leave having heard a lecture about the importance of a healthy diet than with the actual tablets. These complaints occasionally tip over into the word “Stasi,” the word “Nazi.” No one is proud of these moments.

But no one is immune to this impulse to romanticize where you came from — where people did things that made sense, goddammit — when faced with a new culture from which you are out of step. It’s easy to respond to the foreignness of your new home with indignation and “Why, I never!” James’s letters home grow more and more flummoxed as he tries to learn German and interact with the natives. “The language is infernal,” he complains to his family.

“German requires… that you should bring all the resources of your nature, of every kind, to a focus, and hurl them again and again on the sentence, till at last you feel something give way, as it were, and the Idea begins to unravel itself.”

William must have had to bring all the resources of his nature to hurl against the German personality as well, if his experience at all resembled mine. So many hours I’ve spent dissecting evenings out with German men, just to determine whether or not it had been a date! “Well, he paid, but he did not touch me, and that’s the fifth paying-but-no-touching dinner and for Christ’s sake I have met his family what the fuck is going on!” A friend once intervened. “If a German man likes you, he won’t touch you, because he respects you. If he just wants to be friends, he won’t touch you. Basically he’ll only touch you during the first ten dates if he doesn’t care much for you.” And meanwhile they will sit there wrapped in their beautiful impenetrability, never flashing enough vulnerability to let you know if your own advance will be met with anything other than stony silence. It is baffling. Someone should develop a code of hand signals.

I wonder if James tried to make a move on a Teutonic woman during his residency, and if he was frozen by that aloofness. Though, in his letters, he seems just as desperate for the company of men as for the affections of women. He wrote home, “Berlin is a bleak and unfriendly place. The inhabitants are rude and graceless, but must conceal a solid worth beneath it. I only know seven of them, and they are the elite. It is very hard getting acquainted with them, as you have to make all the advances yourself, and your antagonist shifts so between friendliness and a drill sergeant in formal politeness that you never know exactly what footing you stand with them.”

There was always something that worked sadly in William, to borrow his expression. A howling loneliness that put him on unequal footing with men he tried to befriend. There is an element of grasping panic to his letters to Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., as William begs for swifter response. He was in his own bubble in Berlin, unable to communicate, unable to force communication from back home, alone with his thoughts, none of which were good. He could have been standing in the center of Unter den Linden, arms outstretched, his entire psyche unzipped and his tremendous need spilling out of him, and the Germans would have simply brushed past him, without even the slightest Schuldigen in passing.

***

I’m not allowed to leave the university campus with the volumes of James’ letters, so I read them outside, under a tree. Surrounded by twenty year olds, all of them seeming happily grouped up, greeting friends with a double cheek kiss and enthusiastic smiles. When my back starts to ache, a reminder of the age difference between myself and the students around me, I return the books to Dr. Logi’s office, I take the train back to Alexanderplatz, and then I walk the mile home. To an empty apartment, furnished with someone else’s belongings.

I make a cup of tea, I check my email, and I feel the pore-less surface of the bubble around me. I want to bend time, and snatch William out of his lonely guesthouse. I could use the company. But I know how his story ends. He has to stay in Berlin a bit longer, so that he can become a great man. And me? Who knows what the fuck I’m doing.

Every James biographer has a slightly different take on the breakdown, but there is near universal agreement that it has something to do with his father, Henry James Sr.

I have to say that I do not like his father. In fact, I dislike him with such an intensity that it’s clear to me that I am projecting some of my own issues there. He always struck me as being the worst kind of philosopher, even besides the fact that he never had an original thought in his life. He held everyone to ridiculously high standards — his two eldest sons especially — while never once noticing how far from his own mark he fell. His own philosophical framework was either an exercise in great hypocrisy — praising work as the path of true manhood and self-sufficiency while he himself lived off his father’s fortune and never held a job — or an act of self-justification — warping theological thought so that the waywardness of sinning, as with his own drinking problem and lusts, was actually a path to becoming more divine, somehow. He preached that parents must allow their children to be their own selves and make their own way, and yet he demanded total obedience and deference from his own children. In short, he constructed his philosophy as a way to avoid ever experiencing a moment of self-doubt or questioning.

“My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will,” he wrote in his journal on that day. It must have been the first sighting of the North Star. He still spent the next few years in the dark, falling over things and getting depressed. But he was oriented.

As the eldest son, William felt enormous pressure both to achieve a level of respectability and renown and to please his father. There was a burden on him not to disappoint and not to fail. The problem was that his father’s definition of failure kept expanding to encompass anything William tried to do. Henry Sr. was supportive when his sons dabbled in interests, but when they decided on a specific course of action, their chosen field was suddenly never good enough, never important enough, never worthy of his sons’ great potential. His father discouraged William at every turn, and so he skipped from profession to profession, trying to finally step into the light of his father’s approval, only to have it yanked away like Lucy’s football, again and again.

Henry Jr. noticed this perverse tendency in their father, reflecting that the message they received was never to dismiss “any suggestion of an alternative,” that William should not go to medical school because that would prevent his ability to become a painter, despite his already being on the record as not in favor of art as a life path for his son. As if that was not exactly what being an adult is, dismissing potential alternatives to focus on one path. He continues in his memoirs, “What we were to do instead was just be something, something unconnected with specific doing, something free and uncommitted, something finer in short than being that, whatever it was, might consist of.” Henry Sr. wanted his sons to live in a space of limitless potentiality forever, while continuing to judge them harshly on the lack of concrete results.

“Every person gets the father they require” to turn into the people they need to be, a colleague once said to me, but he has flowy hair, wears a lot of purple, and uses words like “fate” and “destiny” in an enviably sincere and unironic way. But here’s the truth: it was this period of indecision that made William James unique. Later, he was able to draw on his art training, his medical training, his philosophical learning, his spiritual experimentation, his psychology background to create a philosophy that is deeply rooted in body, soul, and mind. And without a crazymaking father forcing him in one direction and then another, he never would have, goddammit, lived up to his full potential. That doesn’t mean I do not still sometimes yell at William James’ father in my head when I am reading their letters. “Leave him alone you useless son of a bitch. You’re so goddamn unimpressive you have to suck the lifeblood out of your own children, feeding off their accomplishments like some vampiric stage mom. Back the fuck off.” Etc.

A friend just back from Latvia told me that the way the Russians dealt with the mosquitoes there, big as hummingbirds, was to lace their own food and the food of their livestock with insecticides. They would poison themselves and their own property to kill off the parasites. It would be possible to take the Russians’ lead, with a parent like that, to poison your own ambition so that no one undeserving can lay claim to your success. But then I was always more spiteful than James was, I doubt the thought occurred to him.

And besides, it’s conveniently easy for us to look back on a person’s life and assign the proper causes to the effects. It’s maybe our great tragedy that we have to live our own lives going forward, unable to see a turning point just off to the side, never knowing if our own path will prove fruitful or futile.

***

“I am conscious of a desire I never had before so strongly or so permanently, of narrowing and deepening the channel of my intellectual activity, of economizing my feeble energies and consequently treating with more respect the few things I shall devote them to. This temper maybe a transient one… but something tells me that practically my salvation depends… on following such a plan.” — William James, journal, Berlin

I moved to Berlin with my life distilled down to two suitcases. I’m still not sure if that was an act of pessimism or optimism. The rest was hauled away by my new Craigslist friends, while I drank vodka on ice and nodded when they asked, “Are you sure this is free?” Nothing went into storage, nothing was given to friends to hold onto, just in case this whole scheme didn’t work out and I needed to come back. Maybe in the end it’ll be one of those defining moments that makes all the difference in retrospect. Who knows how long it’ll take for me to get far enough away to tell. But I can’t help that when I come across The Fool card in the tarot, with his funny hat and little dog, boldly stepping off the edge of the cliff, trusting the universe will catch him, I always picture his body dashed to pieces on the rocks below.

After all, throwing away all of my belongings wasn’t really part of the plan. It’s just that when I started to pack, I looked around and only found two suitcases worth of things that were worth saving.

Pessimism, James would write in a later essay, a few years after he wrote the world’s first psychology textbook, The Principles of Psychology, that first book that changed everything, both in the world and in his life, is a spiritual problem. It is a crying out to the heavens to be proven wrong, or at least struck down already. After all, a realist would know that there’s a whole array of possibilities that could result from every small decision. Being impaled on a tree branch at the bottom of a ravine is, yes, one potential outcome, but it’s not going to happen every time. That deep cynicism springs from a “religious demand to which there comes no religious reply.”

There was very little of the abstract in James’s writing interested, as he was, in the full bodied living of life. His comment about pessimism was included, after all, in an essay titled “Is Life Worth Living?” written nearly three decades after his time in Germany.

“He wrote that essay when he was suicidally depressed, you know.” I was in a large hotel bed with a gentleman. Pre-Berlin. Part of the contents of my life I did not want to take with me across the Atlantic. Who knows where my blue dress had landed, although I guess it does not matter. This was my hotel room, not his. The heavy breathing had barely slowed before he began talking about William James again, continuing the conversation that had begun in the hotel bar. I had begun wondering how I was going to get him to leave. “Or, I guess, he was coming out of being suicidally depressed, and there he was, addressing this lecture to a room of young students. He wrote that essay because he was trying to find the answer.”

I think of James as he might have been on that April day. Jacket off. Shirt sleeves rolled up. Sweat on his pale brow. Clutching the lectern to hide the shaking of his hands. Cracking jokes (“It depends on the liver.”) while very seriously deciding whether to do away with himself. Maybe he thought back to the pit he had been in back in Berlin, when “thoughts of the pistol, the dagger, and the bowl began to usurp an unduly large part” of his attention. I wonder if everything that had happened in the intervening years — the fame that came with his first book, the lovely wife, the prestigious position at Harvard — seemed ultimately hollow. After all, even all of that could not keep him buoyed so what could its value truly be. Maybe he thought he should have just gotten it over with all those years ago.

Or, maybe he was actually doing okay, and this guy didn’t know what he was talking about. Maybe I should not consider post-sex conversation with men I don’t care for “historical research.”

God, what is it with me and men and William James? I only started reading him because I had a crush on a boy. A boy who wore a hemp necklace. My romantic degradation knows no bounds. He had announced at dinner one night, out of the blue, that Varieties of Religious Experience was his favorite nonfiction book of all time. It was not the first mention of James; for months his name had been cropping up all around me. I would see him quoted in books I was reading, friends would reference him in conversation. But I had always figured yuck, an East Coast dead white philosopher? Who taught at Harvard? Not for me. It took a pretty face (and a hemp necklace) before I broke down and read Varieties. And then everything changed.

Maybe the universe is just as exasperated as I am, that it has to put its messages in mouths I want to put on mine before I notice its extraordinary efforts at synchronicity.

***

My home in Berlin is built on sand, so it’s not like I’ve spent a lot of money gussying up the place.

“The opera house is sinking into the ground,” Stefan tells me.

“Of course it is.”

My belongings still only amount to a little more than two suitcases. I carry my passport on me at all times, like some sort of international fugitive trying to evade Interpol. My relationship with this city is renegotiated on a daily basis. It is a strange way to live.

The freeing sensation that comes with burning your old life down to the foundations fades surprisingly quickly. At the first sign of rain, you will miss that old roof, inadequate as it might have been. And so there were nights, lying sleepless in a bed I do not own, staring at a painting I did not choose, when I requested the presence of William James. And he would come, the older, more confident version, the one who could see his life backwards, in a three-piece suit and smoking a pipe. (I do not know where the pipe came from, it’s possible I’m confusing him with my father.) Sometimes he would just sit on the edge of my bed and squeeze my foot through the blanket until I got back to sleep. At other times, we would talk. Mostly about the loneliness that is so deep it leads you into conversation with people who are dead.

At those times he would lean his head back and rest his kind eyes on me. “Consider this to be the gloaming,” he would say. “When it’s too dark to navigate by the landscape. And it will get darker still, but then you’ll be able to navigate by the heavens.”

In the midst of his own time in the gloaming, James stumbled upon the revelation that he had free will to direct his own life. It was a philosophical concept, but I doubt it was coincidence that this idea struck him as he first began to challenge his father and reject the beliefs bestowed upon him. “My first act of free will shall be to believe in free will,” he wrote in his journal on that day. It must have been the first sighting of the North Star. He still spent the next few years in the dark, falling over things and getting depressed. But he was oriented. He was moving in one direction that would bring him to a good end.

***

Once you’ve been in Berlin for more than three months — a successful trip to the Ausländerbehörde is usually the starting point — you will start showing up in people’s lists, Everyone I Know in the City to Which You are Moving. The longer you stay, the more lists you will appear on, and the looser the ties will be between you and the new resident. You will buy coffee, you will soothe panic. You will pick up on certain patterns and gain an ability to guess how long someone will stay based on their answers to a few basic questions.

“Did you leave your things in storage in the States?” If yes, they’ll be gone in six months. If you have a safety net, you’re probably going to use it after that first visa meeting, that first month of winter, that first ten page mandatory health insurance application printed in very small German.

“Do you know someone who lives here?” If they came because they have friends in the city, they’ll leave around the same time their friends do, which they will, because it’s Berlin, and almost everyone leaves.

“So. What brings you to Berlin?” If the question brings out that hollow stare, the blank expression, you know they’re going to be here for a while, at least as long as it takes to sort a few things out.

When James left Berlin, he returned to the States to finish his medical degree and then join the Harvard faculty. Now there’s a building on campus named after him. I’ve been thinking of leaving after a few years of life in the bubble, but I am unsure yet where to go. Harvard has yet to call. But after a few glasses of wine I start looking up apartment listings in Trieste, in Dublin, in St. Petersburg. I wonder which one of them I might call home, in the same way I call Berlin home, that is, the “…for now” remains silent. I wonder what it’s like over there, and what I would be like over there.

Related: Welcome to Berlin, Now Go Home

Jessa Crispin is the editor and founder of Bookslut. She can occasionally be found in Berlin.