Irony Is Wonderful, Terrific, Fantastic!

An op-ed appeared in The Times a couple of weeks ago, called “How to Live Without Irony,” and it tore around the Internets like a brush fire. In this essay Christy Wampole, an assistant French professor at Princeton, complained and complained about the hipster, or “urban harlequin” as she styles him. He is “our archetype of ironic living,” who “harvests awkwardness and self-consciousness.”

So what are we supposed to act like, Prof. Wampole, if we do not want to act like an ironical hipster? A four-year-old, it emerges! Or a tree.

Observe a 4-year-old child going through her daily life. You will not find the slightest bit of irony in her behavior. She has not, so to speak, taken on the veil of irony. She likes what she likes and declares it without dissimulation. She is not particularly conscious of the scrutiny of others. She does not hide behind indirect language. The most pure nonironic models in life, however, are to be found in nature: animals and plants are exempt from irony, which exists only where the human dwells.

All I can say is that even the idea of an irony-free culture, with adults skipping around going Hullo Trees, Hullo Sky, can only fill the rational mind with dread.

Earlier efforts to “banish irony” failed, Wampole claims.

The loosely defined New Sincerity movements in the arts that have sprouted since the 1980s positioned themselves as responses to postmodern cynicism, detachment and meta-referentiality. (New Sincerity has recently been associated with the writing of David Foster Wallace, the films of Wes Anderson and the music of Cat Power.) But these attempts failed to stick, as evidenced by the new age of Deep Irony.

Earlier in the piece, Wampole “loosely” defines Deep Irony as follows: “Throughout history, irony has served useful purposes, like providing a rhetorical outlet for unspoken social tensions. But our contemporary ironic mode is somehow deeper; it has leaked from the realm of rhetoric into life itself.” Telling, that “somehow.”

One would have thought that David Foster Wallace’s whomping 1993 attack on irony (“E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction”), perhaps the first (and best) salvo to be fired in this ludicrous battle, would have been enough to stop people writing about “toxic irony” ever again.

[…] American literary fiction tends to be about U.S. culture and the people who inhabit it. Culture-wise, shall I spend much of your time pointing out the degree to which televisual values influence the contemporary mood of jaded weltschmerz, self-mocking materialism, blank indifference, and the delusion that cynicism and naivete are mutually exclusive? […] Or, in serious contemporary art, that televisual disdain for “hypocritical” retrovalues like originality, depth, and integrity has no truck with […] the self-conscious catatonia of a platoon of Raymond Carver wannabes? […]

So what does irony as a cultural norm mean to say? That it’s impossible to mean what you say? That maybe it’s too bad it’s impossible, but wake up and smell the coffee already? Most likely, I think, today’s irony ends up saying: “How very banal to ask what I mean.” […] And herein lies the oppressiveness of institutionalized irony: […] the ability to interdict the question without attending to its content is tyranny.

What more needed to be said? Between Wallace’s famous piece and Rorty’s more rarefied analysis (in Contingency, Irony & Solidarity), nothing at all, with respect to the question. But Wallace’s provisional answer, so often quoted, could stand some serious interrogating. Or a sound flogging, even.

The next real literary “rebels” in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of anti-rebels, born oglers who dare somehow to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse and instantiate single-entendre principles. Who treat of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction. Who eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue. These anti-rebels would be outdated, of course, before they even started. Dead on the page. Too sincere. Clearly repressed. Backward, quaint, naive, anachronistic. Maybe that’ll be the point.

To which I would respond: Mr. Wallace, have you ever considered that irony might actually be an aid to the treating of plain old untrendy human troubles and emotions in U.S. life with reverence and conviction? Because you demonstrated that yourself, again and again.

If the beautifully constructed argument of “E Unibus Pluram” “failed” (it didn’t, I’m just saying “if”), Christy Wampole can scarcely be said to have achieved “success,” whatever that would mean (maybe Todd Solondz would be struck by lightning?). But the truth is that nobody has ever retired from the field a victor; we’ve been plagued with all this blathering on about irony, and hipsters, and ironic distance, and New Sincerity, pretty much nonstop for the last twenty years.

So what I want to say about all this is: NO. Just no, no, look, no, David Foster Wallace RIP; No, Christy Wampole; No, Jonathan D. Fitzgerald responding in The Atlantic: I do not want to live without irony. I do not want any New Sincerity, I do not wish to emulate a plant, just NO. The world is far too dark and rage-making for me to dispense with irony entirely.

Okay, maybe some of us could ease up on the bile a little bit; that is a fair assessment. In certain cases, and naming no names among the present company here assembled. Too much of anything is liable to be a bad thing. There is a continuum, you might say, with the most biliously effete ironist on one end, and larking about all aglow with innocence and sincerity, or Garden State, on the other, and the operations of intelligence and awareness somewhere in the middle.

Irony has its uses and is, in moderation, an absolutely necessary tool for maintaining what passes for sanity in the modern world. Furthermore, an ironic cast of mind is no impediment to holding passionate convictions. Or even sincerity and humility, in reasonable amounts. This idea that irony in and of itself is “toxic” has got to go, and pronto.

In fact the habitual degree of irony is barely adequate to comprehend the disappointment, the distance, the pitch-black comedy, the anger, between the disgrace of how the world is, how we ourselves are, and how we might like things to be. Without such tools, without the ability to concentrate and register our disillusionment and pain, how on earth will we separate ourselves from it all enough to envision a better way?

And yet, the world is not only a disgrace.

* * *

I don’t know what kind of toddlers they spawn Where The Human Dwells, around Princeton. But really, the very idea of four-year-olds as a model for correct behavior! — those narcisisstic little villains who, yes, are certainly irony-free, and unaffectedly direct, and also entirely convinced that their own unmediated instincts are worthy of total indulgence at all times. My husband once coined a motto for toddlers, expressive of this theme: “Who Could Possibly Object To Me?”

That the average four-year-old has ongoingly funny and beautiful responses to the world around him, I willingly concede (q.v. @PreschoolGems). I’m not here to slag the babies. But what actual four-year-olds (as opposed to essay ones) actually require, adorable though they may be, is practically incessant quieting down, reminding of the valid claims of others, and rescue from the potential consequences of their untrammeled wee Ids. You have to remind them all bleedin’ day long, and again the next day, and the next, to share, to apologize, to tie their own shoes, to say please and thank you, to stop and think, for pete’s sake. To apply a little self-criticism and self-control.

That’s all irony really is, in most cases, is just part of the regular, mature exercise of a person’s ordinary critical faculties. Now and then, the extreme case of dyed-in-the-wool irony proceeds from an unnaturally pronounced fear of vulnerability. But in general, irony is only a tacit acknowledgement that our critical faculties are up and running. It’s just the lights indicating “ON.” We say one thing, we mean its opposite. “Oo I have broken my arm. Oh that’s wonderful.”

The Duke of Wellington — Arthur Wellesley, the first one, the two-time Prime Minister — can’t help but spring to mind.

Uxbridge: By God, sir, I’ve lost my leg!

Wellington: By God, sir, so you have!

Or, the Letter from the Duke of Wellington dispatched from Spain in August 1812:

Gentlemen

Whilst marching from Portugal to a position which commands the approach to Madrid and the French forces, my officers have been complying diligently with your requests which have been sent by H.M. ship from London to Lisbon and thence by dispatch to our headquarters. We have enumerated our saddles, bridles, tents and tent poles, and all manner of sundry items for which His Majesty’s Government holds me accountable. I have dispatched reports on the character, wit and spleen of every officer. Each item and every farthing has been accounted for, with two regrettable exceptions for which I beg your indulgence.

Unfortunately the sum of one shilling and ninepence remains unaccounted for in one infantry battalion’s petty cash and there has been a hideous confusion as to the number of jars of raspberry jam issued to one cavalry regiment during a sandstorm in western Spain. This reprehensible carelessness may be related to the pressure of circumstance, since we are at war with France, a fact which may come as a bit of a surprise to you gentlemen in Whitehall.

This brings me to my present purpose, which is to request elucidation of my instructions from His Majesty’s Government so that I may better understand why I am dragging an Army across these barren plains. I construe that perforce it must be one of two alternative duties, as given below. I shall pursue either one to the best of my ability, but I cannot do both:

1. To train an army of uniformed British clerks in Spain for the benefit of the accountants and copy-boys in London, or, perchance,

2. To see to it that the forces of Napoleon are driven from Spain.

Your most obedient servant

Wellington.

Irony can acknowledge our natural, justifiable feelings of insignificance, or show that we understand our subjectivity. With some humor, if we can manage it! Irony demonstrates that we know we are not the center of the universe, that we can hold opposing ideas in our heads. That we can find humor in the contrast between our natural self-centeredness and our likely inconsequentiality, at any given moment. (“Darling, most people are Chinese.”) Which doesn’t mean that we can’t have passionate convictions; it only means that we understand our passionate convictions as existing in a larger world.

So here’s the big thing that Wallace (and Wampole, obviously) managed to miss entirely: irony, too, is instinctive, “sincere,” a natural function of the well-developed adult mind.

And then, Wallace was very wrong to suppose that you couldn’t keep all your irony and add something more to it. For our world, so ravishing, so subtle and so terrible, cries out every day to be simultaneously reviled and adored. However complex our reactions may be, however carefully they may be fashioned, however “natural” and correct we attempt to make them, they will never be adequate to express the powerfully, insanely contradictory impulses occasioned by the human experience on this earth in the waning days of A.D. 2012, this crazy adventure that we are having together.

Nor is it necessary to “eschew self-consciousness and hip fatigue” all the time. (As we earlier pointed out, Wallace continually showed this in his own work, even if he never articulated it explicitly — “It’s called free will, Sherlock.”) Hip fatigue, if we want to call it that, is one valuable weapon in a larger arsenal that will sometimes include a four-year-old’s unvarnished wonder, pleasure, fear or disgust, and sometimes a serpentlike, Machiavellian, six-moves-ahead critical distance. As required.

* * *

The self-help guru John Bradshaw did humanity a great service with his Inner Child thing, but he didn’t go nearly far enough, in my view. The real reality is that each of us is a cast of thousands, containing not only an Inner Child, but also an Inner Teenager, an Inner Drunken Undergraduate, an Inner Acid-Tongued Cynic, and more, each with his or her own claims on our attention and ultimate behavior. The censor, or “soul,” if you like, behind the wheel decides whose directions to follow at any given point. Sometimes the known bad advice of the Inner Foot-Stomping Toddler is just too compelling, alas, to resist.

But the drawling slight is often just as vital, immediate and true as the childlike yodel of wonder and amazement. Why can’t we have both? The answer is that we must have both. We’ll never really want to give up anything that gives us a chance of telling the truth as we understand it. That’s why we never tire of arguing about all this stuff.

Related: Inside David Foster Wallace’s Private Self-Help Library

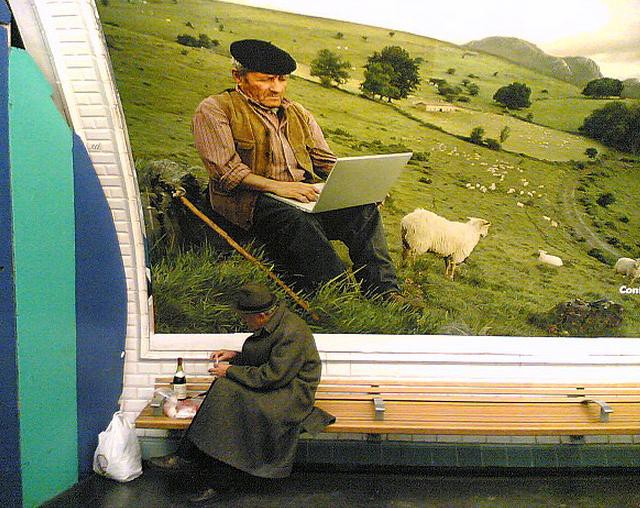

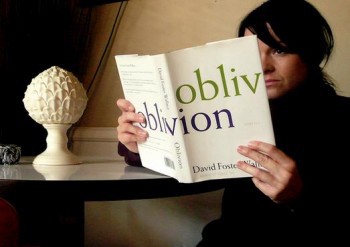

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman. Top photo, from the Paris Métro, by Alex de Carvalho. Self-portrait with David Foster Wallace by Dana Robinson. Thomas Heaphy’s portrait of the Duke of Wellington from the National Portrait Gallery (UK).