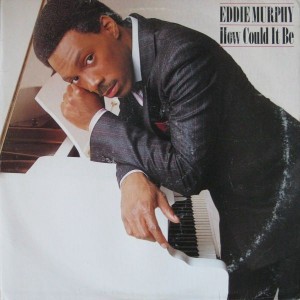

Eddie Murphy's 1980s 'Party' Album

by Mike Barthel

A promo ad for this album says it all: “EDDIE MURPHY SINGS!!! / ‘HOW COULD IT BE’ ?!?” Nine years after Richard Pryor’s …Is It Something I Said? held the number-one spot on the R&B; charts for two consecutive weeks, only one of Murphy’s first two albums, both recordings of his stand-up act, had squeaked its way into the top ten of that chart.

Though comedy LPs by Bill Cosby, Steve Martin, and Bob Newhart had been major commercial successes in the 60s and 70s, by the early 80s, audiences were turning to movies, TV, and video rental for their standup needs. (Pryor’s landmark 1982 concert Live on the Sunset Strip was #1 at the box office, for instance, but only made it to #13 on the R&B; charts.) And so for his third album, Murphy got some of his friends together and launched himself into the revenue stream then ascendant: R&B; albums. Rick James co-wrote and sang on the lead single “Party All the Time,” as you may remember from the tales Charlie Murphy, Eddie’s older brother, shared on “Chappelle’s Show.” The resulting album, How Could It Be, was both an exercise in vanity and astoundingly successful at being the thing it was aspiring to, which was a mid-80s electro-pop megahit. Nearly two decades later, Charlie Murphy’s tales of “Party” are emblematic of its legacy as a reliable go-to for making fun of the 80s. But there’s much more to the album, from Stevie Wonder playing harmonica to sensitive ballads about racial harmony. Does it deserve critical reconsideration?

THE SONGS: Eddie had always pursued music alongside his comedy, fronting an R&B; band as a teenager back in Queens and doing backup vocals for the Bus Boys, a vocal group who appeared in 48 Hours. He included two parody songs on his first, self-titled comedy album — the Grandmaster Flash-goofing “Boogie in Your Butt” and “Enough is Enough,” an almost indescribably embarrassing play on Donna Summer and Barbara Streisand’s disco master class “No More Tears (Enough is Enough).” But you know he’s up to something different here about 30 seconds into the Stevie Wonder-penned opener “Do I.” After an extended intro of Seinfeldian synth-bass pops and guitar strums (that sound, to modern ears, remarkably like an iPhone’s “Strum” ringtone), Murphy coos, “Do I, do I, do I love you…” This is serious Eddie, trading the sexual aggression and rapid-fire mockery of his comedy for vulnerability and romance. If the only song you’re familiar with from the album is “Party All the Time” (and why would it be any other way?), the mellow tone of the rest of the tracks may come as a surprise. They were produced by Stevie Wonder’s cousin, a man named Aquil Fudge, and occasionally featured Stevie himself playing harmonica. There is a song, written by Murphy, called “My God Is Color Blind” which Eddie sings in a pained falsetto, and this song is far more typical of the album than “Party.”

DID IT SELL? Very well: the album went to #26 on the overall Billboard chart, Eddie’s highest ever (although due to the vagaries of Billboard’s system, it did worse on the R&B; charts, reaching a peak 7 spots lower than he did on Comedian). “Party” hit #2 on the singles chart, tragically (yet appropriately) held off from #1 by Lionel Richie’s “Say You, Say Me,” the mere humming of which has been shown to induce spontaneous soft-focus vision and slow-motion hair-flipping in bystanders within a fifteen-foot radius.

CURRENT AVAILABILITY: Available on iTunes as we speak.

SKETCHINESS OF LABEL: Like Murphy’s standup albums, it was released on the mega-major Columbia.

WHO HELPED HIM MAKE IT: I can’t tell you much about the aforementioned Aquil Fudge, who is so little-documented that when the album came out both Billboard and an LA Times letter-writer erroneously assumed this was a pseudonym for Murphy himself. (In retrospect, the idea that Murphy was vain enough to want credit for performing and writing but so modest that he demurred at taking credit for producing does seem ridiculous.) But more than any individual, the free-floating musical environment of R&B; at the time was most responsible for the album’s content. Scan the charts and you’ll find a whole bunch of superstars who shared personnel with Murphy, from Hall & Oates and Marvin Gaye to Eric Clapton and David Bowie. Bassist Fred Washington co-wrote “Forget Me Nots,” which you may be familiar with as “that Men in Black song.” Two years later, Murphy blamed “egos” for the lack of famous guests aside from James on the album (Prince had been a rumored collaborator) and says that the fantastic Mr. Fudge “wasn’t that familiar with the recording equipment we used.” Who would’ve thought that making an album with Stevie Wonder’s cousin would be a bad move!

WHEN HE MADE IT: Eddie Murphy is a hard man to like nowadays, but, in 1985, he was wildly popular. Beverly Hills Cop had been a blockbuster just the year before, following on the heels of the hits 48 Hours and Trading Places. Still, resistance had begun to brew. Two years before, gay rights activists launched the “Eddie Murphy’s Disease Foundation” in reaction to Murphy’s sizable and reprehensible stable of jokes about AIDS and gays. “Too many people were confusing ‘homophobia’ with other diseases, like hemophilia,” the activists write in their pamphlet, “so from now on let’s just call it Eddie Murphy’s Disease.” (He later apologized for all the gay-bashing; it was not particularly convincing.) A 1988 profile in People, written with the release of Coming to America, the movie that would turn out to be the first step in his box-office decline, catches him at a slightly more paranoid place than he was during the making of How Could It Be, but the personality shines through. He says of a fairly complimentary Elvis Mitchell piece that had run in Interview the year before, “I was raped” — and this was a quote that made it into People magazine, the most sympathetic forum for celebrities in the known universe.

How Could It Be was made in the eye of a storm of personal problems that would inform Murphy’s late-80s persona, especially as it was expressed in his 1987 concert Raw. Mentions of paternity suits, real-estate scams, drugs, and nasty business disputes of all cast and character litter any discussion of Murphy’s career during this period. Some of it (the drugs, the money problems) are understandable territory for a guy who’d gotten massively successful at a young age, ricocheting from the then-edgy SNL to making three of the highest-grossing movies of the decade. But the romantic problems were Murphy’s own. The People piece repeats the rumor (more-or-less confirmed in the Chappelle skit) that Murphy would send underlings to clubs to recruit one-night stands. A couple paternity suits followed. The most recent suit was brought by ex-girlfriend, and ex-Spice Girl, Melanie Brown, whose daughter Angel was confirmed to be Murphy’s, though he’s refused to have any contact. Most notoriously, in 1997, while he was married to Nicole Mitchell, Murphy was pulled over by police while out with a transvestite prostitute. Murphy, saying he was only helping out a stranger with a ride home, blamed insomnia.

During this period, Murphy seemed to pick up and discard sexual partners at a frequency greater even than that of other superstars, and he did not treat them kindly. Yet romantic yearning is at the heart of How Could it Be. People quotes Murphy’s friend Arsenio Hall on Murphy’s dating history: “On the first date Eddie will say, ‘Oh, man! Isn’t she wonderful? That’s the next Miz Murphy!’ He wants Cinderella so bad.” And indeed, there’s a yearning for companionship that runs through Murphy’s contributions to the album, one starkly different from the aggressive lothario persona he adopts in his standup.

THE MUSIC: “Yeah, a lot of it turned out bad,” Murphy said of How Could It Be in that 1987 Elvis Mitchell piece. He’s not wrong. Murphy, dreaming of being a star singer as long as he’d dreamed of being a famous comedian, committed the cardinal sin of vanity projects: assuming your undeniable talent in one area will carry over to another area just because you care about and have worked at both areas equally much. It’s clear that Eddie Murphy really wanted to be a serious, respected R&B; singer. But some people have good voices for singing, and some people have good voices for comedy, and rarely do the twain meet. Murphy’s is solidly a comedic voice, and a great one. But the Lionel Richie-like croon he adopts on many of How’s tracks sounds like nothing more than the take from an audition that makes everyone in the control booth exchange disappointed and slightly pained glances. Anyone else would’ve been politely shown the door; Murphy got a gold record. On the bright side, it’s only a half-hour long.

None of this is to deny the magnificence of “Party All the Time,” however. As a song by Eddie Murphy, it’s less than ideal, given that everything we know about Eddie Murphy tends to dismiss the dissatisfaction expressed of girls who indulge in recreational activities with the frequency much-protested in the song’s chorus. But as an 80s synth-pop single, there is not a single thing to complain about. It’s ironic, goofy, and insanely tuneful. Murphy’s weak voice ultimately prevents it from being a vocal-driven egofest, letting the crazy groove and melody dominate. “Party All the Time” is a four-minute loop of pleasure that could be endless, if you want it to be, Rick James whispering in your ear, the bass bouncing along, the chorus occasionally circling back into view. Sometimes the context matters less than the beat.

Previously: Brian Austin Green’s “Beverly Hills 90210”-Era Rap Album

Mike Barthel has a Tumblr.