My Ambitious Attempt To Make Puerto Rican Pasteles

by John Ore

A series about foods we miss and our quests to recreate them.

Like most good Puerto Ricans, my mother was born in the Bronx. But growing up, I spent a decent amount of time in Bayamon, Puerto Rico, where my grandparents lived until I was in my 20s. There, as kids, my brother and I chased lizards in the backyard, enjoyed coconut right off the tree, listened to coqui frogs at night and roosters in the wee hours of the morning through open louvered windows. Everything on TV was in Spanish (which we didn’t speak), so we explored a lot. We were also exposed to some dishes that, while we were too young to appreciate them, I still recall fondly and cherish today.

Pasteles are Puerto Rican meat pies consisting of a filling encased in a masa, wrapped in a banana leaf. I liken them to Mexican tamales in their meat/masa/leaf trifecta, but the similarities end there. I’ve had very good ones in New York, but they weren’t the same as I remember from growing up. The last time I had homemade pasteles was probably at my grandparents’ house in Winter Springs, Florida, 20 or so years ago. Even then, I don’t think my grandmother actually made them: my mother recalls how my grandmother always thought making pasteles was such a hassle that she would buy them from a woman in her neighborhood. As a result, pasteles are considered more of a holiday treat, and holiday dishes are supposed to be a pain in the ass. I don’t believe that my mother has actually ever made pasteles, so I’m probably the first member of my immediate family to attempt this recipe in decades. No, Mom, it’s not a competition (I’m just a better Puerto Rican).

THE HUNT FOR A RECIPE

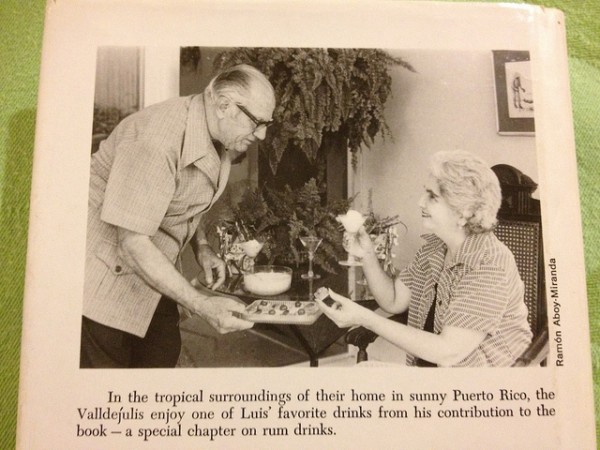

Carmen Aboy Valldejuli’s Puerto Rican Cookery was a fixture in my mother’s kitchen, and I finally procured my own copy several years ago. It’s a delight, and the real deal, detailing recipes for authentic cocina criolla that includes everything from gandinga (whose main ingredients are hog’s liver, kidney, and heart) to finger bananas in wine to guava jelly. I’ve only attempted some of the tamer recipes, like pork chops, and naturally some from the chapter on her husband Luis’ favorite rum cocktails. Come on, just look at those two!

Predictably, the pasteles recipe is an intimidating list of ingredients (yautia? achiote? banana leaves? sour orange juice?) and instructions (crushing in a mortar? removing the skins from chickpeas? wrapping in parchment paper?). Its authenticity was confirmed in the voice of my mother telling me that making pasteles is a daylong commitment and did I really want to bother? Gauntlet, thrown down.

Here’s the exhaustive recipe, as I’ve adapted it from Puerto Rican Cookery. It blends groups of ingredients with prep steps, handily and, at times, confusingly. Quantities below yield of 36 pasteles (!!), but I cut the recipe roughly by ⅔ to get about a dozen. Less commitment if you don’t like the result. In which case, you are dead to me.

THE FILLING

• 2 lbs. lean pork meat, uncooked

• 6 tablespoons jugo de naranja agria (sour orange juice, which I could not find, so I just used straight-up orange juice)

• 4 sweet chili peppers, seeded

• 2 cloves garlic

• 2 tbsp. oregano

• 4 leaves fresh culantro (I used cilantro, since I could not find culantro, except in the achiote seasoning)

• 1 tbsp. salt

• 1 lb. cured ham, cubed

• 1 green pepper, diced

• 1 onion, diced

• 1 ½ cup raisins

• 1 can garbanzo beans (with liquid)

• 1 cup water

• 24 olives with pimentos, chopped finely

• 1 ½ tbsp. capers

• 6 tbsp. achiote seasoning

Rinse and dry the pork meat, chop it coarsely, and mix with the orange juice. I assume this has some sort of ceviche effect on the raw meat. Who knows, just do it. I’ve seen recipes where the pork is cooked, but I stayed true to Valldejuli’s version, and did not die.

Next, crush the chili peppers, garlic, oregano, culantro (or cilantro) and salt with a mortar and pestle. Add the results to the pork mixture, along with the ham, peppers, onion and raisins, mixing thoroughly.

In a saucepan, bring the garbanzos and liquid and water to a quick boil. Pour the liquid over the meat mixture, and remove the skins from the remaining garbanzo beans (if anyone knows an easier way than doing it by hand, one-by-one, I’m all ears!) before adding them to the whole mess. Toss in the olives and capers, the achiote seasoning, and mix everything together while marveling that this entire mixture exists in the first place. Cover it and place in the fridge. The masa is next, so maybe sit down for a breather and have a quick glass of port or something to steel your nerves.

THE MASA

Ready to freak out? Haven’t already? Let’s get ready to make a starchy paste out of unripe bananas and tubers you’ve never heard of!

• 4 lbs. white yautia, peeled

• 4 lbs. yellow yautia, peeled (look, if you are lucky enough to find yautia, just go with what you can find…I found the white ones, and just doubled the amount)

• 15 green bananas, peeled and rinsed in salt water

• 2 cups lukewarm milk

• 10 oz. achiote seasoning

• 2 ½ tbsp. salt

I was lucky enough to find yautia at Steve’s C-Town in Park Slope, along with most of the difficult-to-source ingredients. It seemed like they knew I was coming: I found parchment paper next to the yautias, which rang up as “pasteles paper.” Yautia is a starchy, pale-fleshed, slippery root vegetable that I’ve never even considered before I embarked on pasteles-making.

Wash, drain, and grate the yautias and bananas. Traditionally, a mortar and pestle was used to crush these two ingredients together, gradually adding the milk as you went. Trust me when I say that a food processor is a huge asset here, even though I hate cleaning up after using a food processor (yeah, I know: First World Problems, yadda yadda). Grate the yautias and bananas first, then drop them in the food processor, and pulse while slowly adding the lukewarm milk until you get a nice smooth grainy pasty sort of an arrangement. Stop before it completely liquefies. You’ll know.

Transfer to a bowl and add the achiote coloring and salt. Goya makes a convenient achiote and culantro seasoning mix, which was perfect for this recipe. However, I used all of it in the filling, so I had to substitute with achiote paste. Turns out, you need a lot of it, and the resulting color turns the masa into a pleasant brick red.

THE ASSEMBLY

Here comes the fun part! Ever worked with banana leaves? Me neither! But if you can’t find them — super-brand Goya offers banana leaves that I found in C-Town’s freezer case — you can always use plain parchment paper. If you can find banana leaves, you’re gonna use both.

Goya’s packages of frozen banana leaves are nicely portioned: once you defrost them, it’s easy to divide them into 12×12-inch squares. They are a bit fragile and seem to tear easily, so be careful since breaches in the leaves result in a messy leak of masa and filling during assembly. Wipe the inside of the leaves with a damp paper towel, and set them aside for your assembly line.

(While I’m recommending cutting the ingredients by ⅔ to yield about a dozen pasteles, you’re going to want to use the following measurements for assembly to ensure the correct robust portions.)

Spread about 3 tablespoons of the masa on a banana leaf, smoothing it out until it is almost transparent and about 2 inches from each edge of the banana leaf. Best bet is to use the back of a spoon to scoop and then distribute the masa on the banana leaf. Then plop 3 tablespoons of the filling into the center of the masa.

Fold the bottom edge of the banana leaf up to meet the top edge, then fold the resulting bottom crease up to meet the top edges again. Now fold the sides in towards the middle like little wings, and place flaps-down on a sheet of parchment paper. Fold the parchment paper over the wrapped pasteles in a similar manner as you did with the banana leaves, and tie them off with butcher’s string. You’re now left with tidy little packages of Puerto Rican goodness. Tie them together in pairs, with the seams facing each other.

Now what are you supposed to do with them? Bring a pot of lightly salted water to boil, and drop in the pairs of pasteles, parchment paper and all. Cook, covered, for 1 hour, flipping them over halfway. When finished, remove them from the water immediately, remove the parchment paper and serve.

Unwrapping the first pasteles we cooked was nerve-wracking: after all we’d been through in terms of sourcing, prepping, and assembling the damned things, they could never live up to my memory or the anticipation of building them. The familiar aroma, however, immediately reassured and calmed me (along with a couple of glasses of red wine). They say the sense of smell is the strongest trigger of memory, and I was instantly transported back to my grandmother’s kitchen, listening to my grandfather lecturing me on the importance of changing the oil in my car. While I remember pasteles as having more of a greenish hue, the brick-red tamale shape of these wasn’t altogether unfamiliar. The first bite confirmed I’d hit the jackpot. Not only were they empirically awesome (if I do say so myself), my pasteles immediately conjured and compared favorably to the flavors I remembered from my youth, right down to the texture of the masa and richness of the filling.

My wife and I enjoyed the first two pasteles of the batch, and froze the rest for the holidays. Somehow, I’d pulled it off. We’ll see if my mother agrees.

Previously in series: My Attempt To Make Jamaican Escovitch Without The Burn

John Ore has a freezer full of extra banana leaves, if you need some.