A Complete History Of Gerbiling So Far

A Complete History Of Gerbiling So Far

by Jane Hu

The act of gerbiling, according to the Internet, is simple. In most instances, it involves a tube up the ass, followed by a gerbil up that tube. Some accounts suggest that the gerbil should be declawed as a safety precaution, but the main gist is to have the gerbil burrowing around one’s anus long enough to bring about sexual pleasure. One might lure the gerbil up the tube with a piece of cheese, or, inversely, light a flame under the funnel to send the gerbil scurrying. I have seen more than few suggestions that drugs (for the gerbil) might also be helpful. For men, the burrowing of the gerbil stimulates the prostate gland, which can provoke spontaneous ejaculation. For women, there are options on where the gerbil can be introduced (thanks to one porn video site, I can confirm this). But whatever the variants, the equipment at its most basic is: Tube. Gerbil. Orifice. The concept is really not that hard to follow, even if its execution might generate other complications.

More compelling than how it happens, though, is the question of how often. Investigate even a little and you’ll find a large part of gerbiling lore is taken up not with mechanics, but with the activity’s status as urban legend. As this Urban Dictionary entry reminds us: “Although the rumors of this practice have been around since the early 1980s, with thousands of Google references to this, not one documented case of the practice exists.”

So why does the endless fascination about gerbiling continue? How is it that, even now, we’re unable to state with any conclusiveness whether gerbiling first emerged as an actual sexual activity practiced by real people — or as mere titillating legend? Was there an Original Gerbil, an Original Gerbiler? The why and wherefores of gerbiling seem bottomless.

I SMELL A RAT

In the hard-boiled clichés of noir fiction, there is often a rat to be sniffed out — one that scurries and hides — but is always betrayed by his miserable scent. This premise pretty much works in our case too; just substitute one rodent for another. In the 1931 film Blonde Crazy, a mobster by the name of Bert Harris (played by James Cagney) points a gun at his victim and says what is now a rather notorious line (that, like our gerbiling story, seems to get tweaked with each retelling): “Mmm, that dirty, double-crossin’ rat.” The culprit here is one Joe Reynolds and, in this instance, he’s hiding in a closet.

The rat and old Joe in the closet: they have never been so close as in the case of gerbiling. “Gerbil-stuffing,” as some call it, has since entered the pantheon of Stuff Gay Men Do. While some contemporary folklore include tales of rodents inserted up women’s vaginas, the very first mentions of rats in asses are explicitly tied to male homosexuals.

Folklorist Norine Dresser digs through this history in her 1994 essay “The Case of the Missing Gerbil.” With a title that nods to Raymond Chandler’s own detective stories, Dresser seeks to find the narrative origins of, to use her precise phrase, “rodents inside rectums of homosexuals.” The tales she relates appear more than a little apocryphal (Dresser says as much), but they have somehow travelled from the realm of hearsay into that of maybe-so — like so much to do with gerbiling. One story goes like this: during the Vietnam War, American soldiers would dodge the draft by letting a rat tail dangle from their anus and, as such, signal their homosexuality (then strictly forbidden in the military). In an odd way, these men seemed to anticipate the “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy by preemptively show-and-telling, though, of course, to different ends.

In 1990, a piece titled “The Trouble with Gerbils” ran in the LGBT publication The Advocate. In it, media critic Catherine Seipp mentions a TV weatherman from Wichita, Rick Segal, who was pressured into resigning from his job because of gerbiling rumors. Scant consolation to Segal but he wasn’t the first newscaster to be so afflicted. In the early 80s, as is recounted here, a Philadelphian KYW newscaster named Jerry Penacoli suffered career damage after a rumor started that he had visited a local emergency room to have a gerbil removed from his colon.

THE RUNAWAY GERBILER

Two local newscasters, both prominent in their cities. Celebrity: this is what really drives a good gerbiling story. A rumor is always more salacious with someone famous attached. In Seipp’s 1990 article, she describes a conversation with a supervisor for the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, who estimated having heard gerbiling stories attributed to at least ten different celebrities over the past couple decades. Especially during the 80s — when these tales were at their buzzing prime — the whiff of gayness that came with handling a gerbil brought some truly offensive smells to the happily, concertedly heterosexual halls of Hollywood.

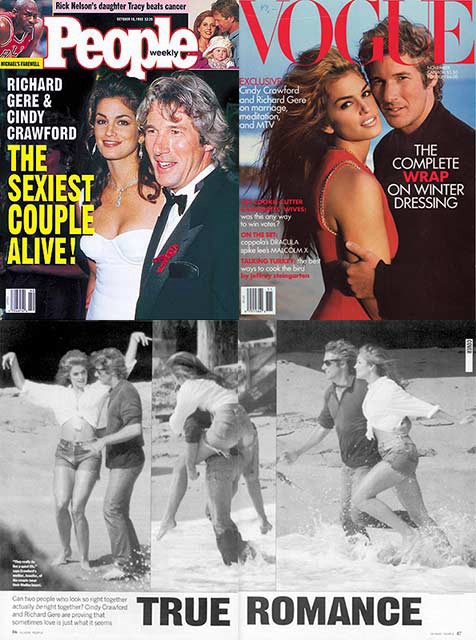

Now, enter the most notorious (supposed) gerbiler in the history of gerbiling, the one whose very name you’ve anticipated from the start of this piece: Richard Gere. Speaking of the angel city, William Faulkner once described it with the following disdain: “Hollywood is a place where a man can get stabbed in the back while climbing a ladder.” And it does seem that at the height of Gere’s hot glory, someone decided to whip out the gerbil — and stick it up his ass. The story (and as far as we know, that’s all it was — a rumor, a myth) went something like this: sometime in the 80s, Gere was admitted to the emergency room of Cedars-Sinai, an LA hospital, because a gerbil had gotten trapped in his rectum. The gerbil was successfully removed, and Gere went on to star in his most successful film to date, An Officer and a Gentleman — triumph! But that’s not to say that the gerbil did not leave a significant mark.

Jokes about Gere and Gerbil (who, at one point, was tagged with the casually racialized name “Tibet”) became fodder for media cheap shots. Dresser posits that the story of Gere’s gerbilectomy was “much more wide-spread and enduring than its predecessors, with associated allusions in tabloids and sly references on radio and TV.” During the 1992 Super Bowl halftime, ‘In Living Color’ TV stars made reference to it. Sam Kinison milked it in his lead joke for the 1990 out-of-London music awards, which was broadcast to the largest audience then yet connected by satellite.

Now this is where the unknown provenance of Gere’s gerbilectomy begins to grate on me. The above allusions were all made post-1990, but ask any Gen Xer and you’ll be told that Gere’s story was permeating the gossipy ether for years before then. Don’t take my word for it or anything, but the alleged gerbilectomy happened circa An Officer and a Gentleman (1982) and definitely years prior to Pretty Woman (1990). Yet it was treated as a new rumor when it circulated in 1990.

While commercial internet wasn’t in existence for these earliest mentions of gay gerbiling, one site offers a clue as to where one might begin to chase the gerbil paper trail. Straight Dope author Cecil Adams received a letter about gay gerbiling dated March 28, 1986 that asked about “the mechanics and philosophy of gerbil stuffing.” Cecil’s response is consistent with others of its ilk in that it concludes with his hands thrown up:

I’ve checked with numerous sources in both the gay and medical communities, and though everybody has heard about gerbil stuffing, every attempt to track down an actual case has come to naught. The whole business sounds completely nuts, and implausible to boot.

Unlike others, though, Cecil does pull out at least some descriptive (if not verified) threads:

Rumors of gerbil (and mouse or hamster) stuffing have been circulating since about 1982. In 1984, a Denver weekly said it had a confirmed report of gerbilectomy in a local emergency room. The Manhattan publication New York Talk reported several years ago that New York doctors first caught on to stuffing when they started encountering patients with infections previously found only in rodents. But no such case has ever found its way into the formal literature of medicine.

If gerbil rumors did start circulating around 1982, then they coincide with An Officer and a Gentleman, Gere’s last big hit before Pretty Woman. The date of the Denver publication — 1984 — would also coincide with what was probably the first printed citation of gerbiling, by one Jan Harold Brunvand.

IS THERE A DOCTORATE IN GERBILING IN THE HOUSE?

In search for an authority on gerbiling, you may wish to consult a learned volume on the subject. Which learned volume? Well, the pickings are slim. The Wikipedia entry on “gerbilling” refers to American folklorist Jan Harold Brunvand’s Encyclopedia of Urban Legends, Ed.1 (which draws on information from academic journals). Brunvand also wrote a short piece titled “The Colo-Rectal Mouse,” which appeared in the “Medical Horrors” section of The Mexican Pet, his book on urban legends published in 1986. Here is a section from that entry:

In Fall 1984 I heard five versions of this story from places as scattered as Pennsylvania, through the Midwest, Colorado, Utah, and southern California. Correspondents — particularly from New York and California — have continued to mention the story through 1985. In one recent variation (“gerbiling”) it is said that the gerbil is first put into a plastic bag and given a shot of laughing gas to pep it up a little.

Now, I’m not saying that those 1984 stores included Gere, but I’m not not saying that either. When I emailed Brunvand for further details, he declined my request for an interview. After providing a few citational details for the Wikipedia entry, he told me: “Beyond this I have nothing further or new to say about ‘Gerbilling.’”

I wonder if Brunvand ever got a call from Mike Walker, the National Enquirer gossip columnist who had once spent months attempting to verify the Gere rumors. “I’ve never worked harder on a story in my life,” Walker told the Palm Beach Post in 1995. You can probably predict the end of Walker’s story. After much investigation, he was unable to find any evidence that the Gere incident ever happened: “I’m convinced that it’s nothing more than an urban legend.”

Brunvard had “nothing further or new to say about ‘Gerbilling,’” and the more I pursued this story the more I sympathized, wondering if there really was anything new to say, any originating story to track down, any First Gerbil to be caught. Or was there only a mirrored hallway, gerbils infinitely repeated in reflection, with the first one not even real — just an image of an image. The story seems an urban legend to its empty cardboard core.

Before abandoning this particular line of inquiry, I spoke by phone with Michael Musto, whose landmark gossip column La Dolce Musto has been running in the Village Voice since 1984, the year that interests us so much. His response didn’t open up any leads to the potential origins of gay gerbiling so much as negate them altogether.

As he told me, “Both are total myths: the fact that gay men like gerbiling, and the fact that Richard Gere likes gerbiling. So, y’know, to say that the Gere thing stemmed out of some gay phenomenon is kind of crazy ’cause that was a myth to begin with. It just became one of these incredible urban legends like the Rod Stewart story.”

When asked if he remembered when or where he first encountered Gere’s gerbiling tale, Musto couldn’t recall.

“So mostly it was just by word-of-mouth?” I asked.

“Yeah, it was just there and everywhere you turned. But,” he went on, “it was a much darker time.”

WORLD’S OLDEST LIVING SEX GERBIL TELLS ALL

As urban legends go, the illicit rodent tale tends to have a few identifying hallmarks that stay consistent even as other details vary: the act often takes place in Los Angeles or San Francisco, and always with a gerbil. (Nevermind that you can’t even legally keep gerbils in California due to its threat to the ecosystem.) The paradox of urban legends, though, is this: if they are by definition unsolvable — if they are implicitly so very ungrounded from reality as to be legend — then why do we afford them so much attention?

Take the re-emergence of the Gere and Gerbil rumor in 1990, for instance. Its comeback, if you will. Dresser’s essay makes sense of this particular date by noting its concurrence with the release of Pretty Woman. In one version of the story, as it recirculated, Gere was accompanied on his trip to Cedars-Sinai by Cindy Crawford (to whom he was married from 1991–1995) by his side. What was it about his portrayal of a rich businessman onscreen or his marriage to a supermodel offscreen that prompted the resurgence in the rumor? Or did it have nothing to do with the particulars of his history right then, and everything to do with the fact that after an eight-year period of largely forgettable roles, Pretty Woman had given people a reason to talk about Gere again. All the many sides of Gere.

Shortly after the movie’s release, a phony letter addressed from the Association for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was sent over fax across Hollywood accusing Gere of “gerbil abuse.” (The reason why Seipp was speaking with the supervisor for her Advocate article.) This phony letter is the most real document of the entire gerbil saga. Another thing that actually happened: in a 1991 interview, Barbara Walters asked Gere about certain “salacious rumors.” Gere responded with his own euphemism: “If I am a cow and someone says I’m a zebra, it doesn’t make me a zebra.” (A couple years later, a People story on Gere and Crawford’s relationship, including this mention of the rumors: “Nor has Gere appeared to take the talk at all seriously. ‘It’s kid stuff,’ he told an Associated Press reporter in February. ‘Kids in a schoolyard.’ Has his willingness to champion gay causes — most recently by being one of the first major stars to to take a role in the HBO movie And the Band Played On — fueled the talk? Friends say Gere is simply indifferent to such nonsense. ‘It is a nonissue to him,’ says Pretty Woman producer Steve Reuther.)

Other public references include a Century City Pet Shop in Los Angeles that placed a sign over an empty gerbil display reading: “Don’t worry, we’re not stuck, we just like tight places.” In 1982, cartoonist Gary Larson had sold a mug with the image of two cats mulling over a box of assorted rodents. The caption reads: “These little ones are mice…These over here are hampsters…Ooh! This must be a gerbil!” — in 1990, when the Gere gerbiling rumors took off again, the cartoon was sold in the form of a Christmas card.

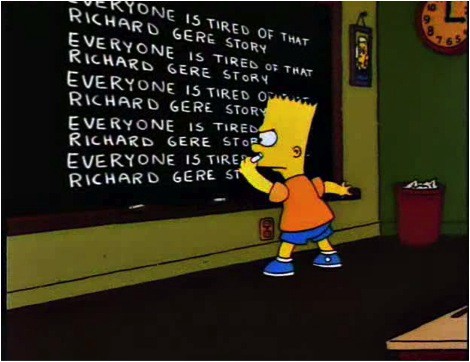

By 1997, “The Simpsons” was treating Gere and Gerbil as old news. The opening sequence to “The Cartridge Family” episode shows Bart scribbling “Everyone is tired of that Richard Gere story” over and over on the chalkboard. While “the Richard Gere story” itself is too tired to bear restatement, Bart’s repeated inscription of the fact of the story stands as its own ironic echo of a tale tired, relentless, and finally unsubstantiated.

Still, the talk didn’t end there. Much later, in 2006, another rumor about Gere began making the rounds — this time a rumor about his rumor. Was it possible that Sylvester Stallone — a nemesis of Gere’s after their fallout on the set of The Lords of Flatbush (1974) — was behind all this? During a Q&A; held on December 10, 2006 for Ain’t It Cool, Stallone responded: “Richard was given his walking papers and to this day seriously dislikes me. He even thinks I’m the individual responsible for the gerbil rumor. Not true…but that’s the rumor.”

What’s peculiar about this quote is how the question to which Stallone was responding hadn’t included any mention of Gere or gerbils. The question, in full: “Could you share an anecdote or two about the filming of ‘The Lords of Flatbush’?” Perhaps Stallone’s animus toward Gere meant that he simply couldn’t let the opportunity to let a gerbil dig pass, but as far as one can tell, Stallone’s frustration over Gere’s paranoia was real. The comic consequence of voicing it in public, though, was that he himself precipitated an entirely new storyline about how maybe he, Stallone, really was at the center of this web of lies.

The durability of the gerbiling rumor, which has followed Gere for more than two decades, speaks to how the contemporary imagination perceives celebrity. When the Gere rumor first started in the 80s it was pre-Internet times. In her 1990 article, when the story re-emerged, Seipp mentions that the rumor was spreading via “a flurry of fax activity” (!). Gossip was gaining speed, but still nothing like today. In the days that followed Stallone’s 2006 Q&A;, sites such as celebitchy, The Hollywood Gossip, and gay-interest spaces such as Towleroad had reported the news.

Fame no longer runs on word-of-mouth. With online forms of virality, memes can be traced back to their first typed form. In a sense, the detective work involved is easier since it doesn’t require going offline and searching through books for lost scraps of the physical world. Online gossip, reinforced by concepts such as “the scoop,” seems to preclude the possibility that news can emerge independently from disparate sources. Take the Stallone story, for example; while picked up across various media circuits, its provenance was never questioned.

Celebrity gossip also has the tendency to make even the non-famous paranoid, especially online. Now, any secrets you may have — no matter how small or mundane — might suddenly come to light. Is our obsession with celebrity gossip partly a way for us, as vulnerable online users, to vicariously work through anxieties regarding our own privacy?

Shortly after Gere and Gerbil (Part Two), another gerbiling story made it big, this time involving two gay men from Lake City, Florida: Vito Bustone and Kiki Rodriguez. This story can be traced back as far as two online Usenet threads. An alleged 1993 Bloomberg Financial Services article was said to have reported:

Rodriguez had orgasmed and demanded the removal of the rodent. Bustone however could not see up the tube. To help him see, he lit a match lighting intestinal gas tapped in the tube. The flame shot up the tube lighting the fur of the Gerbil, and detonating a larger pocket of Gas behind the hapless animal.

Another telling of Bustone and Rodriguez’s story was posted on Usenet almost a year later, on February 14, 1994. Here the basic contours remain the same, with some slight tweaks. For instance, the Bloomberg Financial Services version of the story ended with a quote from Sheriff Hugo Root: “It serves the faggots right.” The 1994 post also concludes with a quote from Hugo Root: “It’s Faggot I feel sorry for. Being stuffed up some queer’s trademan’s entrance.” (The gerbil’s name was, apparently, Faggot.) It’s not hard to see the 1994 quote as a knowing modification of the one from 1993, but it’s even less hard to see either of them as anything but knowing fabrications from the start.

Snopes.com attributes the origins of Bustone and Rodriguez’s story to a “faked United Press International item,” which had appeared online. Another version, continues the Snopes entry, had been attributed to the Los Angeles Times — this time situating Bustone and Rodriguez in Salt Lake City. Ultimately, it seems “neither news outlet ever published a news article about these fictitious events.” I’m going to take the entry at its word here, as would perhaps The New York Times which tells us that Snopes.com is the “only place to go for debunking or confirming the latest bit of rumor that just came into your e-mail.” There might never be an official final word on the Gerbiling Beat, but Snopes’s word seems as good as any. As one Sean J. Crist stated forebodingly in the 1993 Usenet thread: “The gay media was not able to turn up even one case where this had happened.”

As these threads make especially obvious, so much of the perpetuation of gerbiling stories depends on how much trust their audiences place in the memory of strangers. For instance, a Usenet thread that began with, of all things, questions about the existence of Walt Disney’s exclusive members-only Club 33, then led to a discussion of a sexualized Mickey Mouse (a most beloved rodent himself), and concluded with this anecdote from a Jim Jones:

I first heard about gerbiling in 1985, while working for a software company next door to the San Francisco AIDS Foundation. Our facilities manager went over to talk to them about something, and came back with stories about posters on the walls that warned against sexual practices that we had never even heard of before — including gerbiling.

Sounds plausible, right? What’s more, why would someone make it up? These are exactly the kind of rhetorical questions gossips want you to ask. Yet, there’s something about the implicit uncertainty of gossip that makes the nebulous tale all the more threatening. Do we share stories to feel like we have an in, or to keep others out?

Sharing gossip creates spaces of imagined communities, online or off. Just, in this case, the gay gerbiler is always definitively on the outside. This narrative device, used to ruin a movie star’s reputation, became an actual narrative device in movies. In the 1991 film The Hard Way, James Wood (portraying a cop) sarcastically tells Michael J. Fox (playing an actor!) to “Do what you do in Hollywood — gerbil racing.”

WHAT GAY THINGS ARE THE GAYS DOING?, UNGAYS ASK

When Jim Jones responded to that Usenet thread on Club 33, he was speaking as just another voice on internet. Jones had no apparent authoritative or public stake in gerbiling, nor did he seem to want to swerve readers with some personal verification of a celebrity gerbiling rumor. Especially when read against other accounts on the authenticity of Gere’s gerbiling, Jones’s anecdote (a story just specific enough, aka not too specific) makes me want to believe. “I first heard about gerbiling in 1985,” Jones writes, “while working for a software company next door to the San Francisco AIDS Foundation.” So far, so plausible.

So here is where I want to point to the elephant (or is it mouse?) in the room — that what fueled the gerbiling legend wasn’t so much TV anchormen, the homosocial embraces in An Officer and a Gentleman, or Gere’s ambiguous sexuality, but the AIDS narrative (however winding and misconstrued it was) during the 80s. As Jones’s anecdote suggests, the connection between gerbiling and AIDS seems almost too obvious to note outright. There they are, Points A and B; who needs even to bother drawing a line between?

In 1988, the International Folklore Review published an article by Becky Vorpagel titled “A rodent by Any Other Name: Implications of a Contemporary Legend.” In it, Vorpagel calls the gerbiler by “Jerry” (aka Jerry Penacoli, the Philadelphia newscaster); Dresser, seeing the name as a gerbiler’s pseudonym, adopts it in “The Case of the Missing Gerbil” to refer to Gere. (See how this could get confusing?) The reluctance to identify these figures by name, however, suggests that the particular celebrity isn’t so much the point here. The celebrity might change; what remains constant is the wish to pin the tale on someone. Vorpagel identifies this impulse and the legend’s popularity “to its functioning as an expression of public unease about homosexual practices, compounded by anxiety about AIDS.”

At the start of the 80s, gay men were already perceived as socially and sexually deviant. And if anything is not a secret, it’s how especially openly homophobic American culture was throughout this decade. With the addition of AIDS and its attendant narrative of Gay Desires Being Punishable By Death, there seemed to be concerns in the mainstream that maybe gay people, already alienated, weren’t being alienated quite enough. Toss interspecies sex with small dirty rat-like creatures into the mix, and you simply get a variation on a theme: gay sexuality as a realm plagued with abnormality, shame-inducing behaviors, and incomprehensible stupidity.

As AIDS grew increasingly visible throughout the 80s, Americans were failing, quite atrociously, to comprehend the reality, mechanics, and science behind AIDS. On May 2, 1983, the Daily Telegraph published a piece titled “’Gay Plague’ May Lead to Blood Ban on Homosexuals,” while the Daily Mirror printed its own “Alert over ‘Gay Plague.’” Not much later, the Sun followed with a piece headlined “U.S. Gay Blood Plague Kills Three in Britain,” while the British tabloid Sunday People came out with “What the Gay Plague Did to Handsome Kenny” that summer. (You know what they did, it seems to suggest.) Sociologist Antony Vass published the rather sensationally titled AIDS: A Plague In Us in 1986 (possibly finding the colon an ongoing and irresistible source of drama, Vass had published Sentenced to Labour: Close Encounters with a Prison Substitute two years earlier). When AIDS diagnoses shot up during 1983 to 1984, the gerbiling story was only one of many ways in which the public tried to define the threat of gayness.

The New York Times can be counted among the newspapers with an early, terrible record on AIDS. James Gleick (who edited Maureen Dowd’s AIDS piece for the Times, one of the first stories the newspaper ever printed on the epidemic, recalls the pressure in the newsroom to “never to print anything that could be construed as approving of homosexuals or homosexuality.” Gleick describes the paper’s reticence during this time as a “shameful slowness.”

The Times archives remains, however, a lens through which we can get a sense of the information the general public was receiving about AIDS. In the early 80s, many people understood the disease as an airborne virus, looming in the ether. (To use Musto’s words regarding the Gere’s rumor: “it was just there and everywhere you turned.”) One Times piece, published on August 8, 1982, quoted a 28-year-old law student: “It is frightening because no one knows what’s causing it. […] Every week a new theory comes out about how you’re going to spread it.” The law student had visited the St. Mark’s Clinic in Greenwich Village because he had been told his swollen glands might be a sign of AIDS.

During 1983, the San Francisco Police Department had equipped patrol officers with special masks and gloves for the purposes of dealing with what they considered “a suspected AIDS patient.” “Theories about AIDS abound among scientists,” as another 1983 Times article puts it.

Nor was the scientific community the judicious fact-based counterpart to journalism. The Journal of the American Medicine Association published a 1983 piece on “Immune Deficiency Syndrome in Children” that spread false generalizations about casual household transmission of AIDS to children, cobbled together from eight case studies. Just as every rumor about AIDS was also a rumor about gay men; many scientific theories of the time were attended with the physical and psychological dangers of gayness.

In her book AIDS in the UK: The Making of Policy, 1981–1994, Virginia Berridge explores early British understandings of the AIDS crisis. She cites Dr. Peter Jones — stationed at the Newcastle Haemophilia Centre — who drove an AIDS patient to the hospital using his own car because ambulance and other medical staff believed the disease to be contagious via physical contact, sexual and non-sexual alike. Dr. Jones reflects:

I felt…quote brave…then three hours later when my youngest son sat in the same seat, I suddenly realized how easy it was to become uneasy. […] My professional perception of AIDS was for a short while overpowered by the public perception…this was a mark of how the atmosphere of panic was getting through.

In the United States, there existed a similar sense of the unknown. A 1997 essay on the medical response to the AIDS epidemic in San Francisco (1981–1984) begins with a preface acknowledging, “we experienced first hand some of the excitement of medical detective work.” The “detective work” necessary to separate the scientifically accurate and ethical, from the false information generated by panic and confusion, much of it perpetuated in the media, is never easy or certain work.

With AIDS, as with gerbils, the desire to link the disorder to a medical source — indeed, in gerbiling stories, to assign it a particular hospital location (e.g., Cedars-Sinai) — has been a way to normalize the narrative of gayness by medicalizing it. It also allows rumor and innuendo to go out donned in the white coat of scientific authority. Theorist Leo Bersani prefaced his famous AIDS essay “Is The Rectum A Grave?”, written in 1987, with an epigraph from AIDS researcher Opendra Narayan of John Hopkins Medical School. (Narayan, by the way, dealt primarily not with human subjects, but with animals.) This was the Narayan quote Bersani used in full:

These people have sex twenty to thirty times a night. . . . A man comes along and goes from anus to anus and in a single night will act as a mosquito transferring infected cells on his penis. When this is practised for a year, with a man having three thousand sexual intercourses, one can readily understand this massive epidemic that is currently upon us.

This comes from someone, as Bersani puts it, with a “presumably high level of professional expertise.”

Not too long after the gay gerbiling rumor made its splashy early 80s debut, Doctors David B. Busch and James R. Starling published a surgical-stats report in Surgery titled “Rectal Foreign Bodies.” This 1986 article, which gathered information from prior literature on Rectal Foreign Bodies (or RFOs), is the most frequently cited scientific document when it comes to gerbiling. Busch and Starling tabulated 182 cases by type and number of objects, among which included two whip handles, one plastic rod, one bottle with an attached rope, and one frozen pig’s tail. No gerbils, though. Not even a tail.

Busch and Starling’s survey is frequently used to end the conversation on gerbiling: the doctors have cataloged all the different things found up people’s asses and, when it comes to gerbils, there has been not even a whisker. As with Rod Stewart’s alleged stomach pumping, the hospital visit cannot be verified, because the hospital visit never happened. Even when the American Hospital Association published the entry “rectal mass — gerbils” under the category of emergency-room procedures requiring 25 minutes to perform, the reality of rectal gerbiling was dismissed. The author of the section, John A. Page, chalked the entry down to a joke.

Yet as much as the concept of gerbiling might make one giggle, the logic of the joke is more hostile than not. As with gossip, the individual at the center of the gerbiling story is always somebody else. If they’re famous, well, the better to break them with it. The supposed facts and truths of gay men’s sexuality can quickly turn into psychoanalytical fodder for the straight world. More worrisome, the psychoanalyzed gets no say or part in these sessions. Their gay body is never present in these cases especially since because they were never there to begin with.

When we look for the Original Gerbil, we do, after all, most likely know the source: it scurried out from the straight imagination. But once you burrow deep inside a gerbil rumor, is there any going back?

Related: A Timeline Of Future Events and A Little History Of Blackmail

Jane Hu isn’t afraid to go deep. Photo by Camilo Torres, via Shutterstock.