How To Make 17th-Century Delights: Curd Cakes

by Gina Patnaik and Lili Loofbourow

A series about recipes that may seem odd or outmoded and yet we’re curious to try!

As 17th-century delights go, curd cakes sounded good. Kinda like comfort food. When the two of us first came across the recipe, we placed bets on where curd cakes might fall on the Elegance-Meter. Were they dukes or peasants? Might (Dame) Maggie Smith have said, “What is a curd cake?” on “Downton Abbey” (back when it was good), or would she have readily ordered them up for tea? On the whole, curd cakes seem less festive than our previous concoction, whipp’d syllabub, what with the latter’s spume and special drinking vessels that draw up the froth-infused wine from below. Curd cake felt simpler. Humbler.

WERE WE RIGHT?

So, one of us (Gina) is trained as a chef. The other one (Lili) can’t cook, but loves 16th- and 17th-century recipe books. Together, we experiment. Trouble is, because we’re both grad students (she’s a modernist, I’m an early modernist), we tend to have very different ideas of what sort of experiment we’re conducting. For Gina, time in the kitchen leads to investigating alternative recipes and figuring out how these foods came together and evolved over time. Lili’s in it for the language (Candyed Eringo-Roots, Neats-Foot Pye) and the good eating. And so, while curd cakes are the ancestors of author Kate Christensen’s delicious nostalgia fritters, featured here the other week, our cooking efforts usually involve a couple of different goals.

Gina: “Our mission: to track down the true history of the curd cake.”

Lili: “Or just to find out what other things curd cakes were called? (And may I have more, please?)”

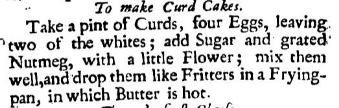

As with our whipp’d syllabub, our starting point was the 1696 edition of J.S.’s The accomplished ladies rich closet of rarities, which offers the following recipe:

In modern proportions, we estimated that might look like this:

• ¼ cup flour

• 2 tbsp sugar (or to taste)

• 1 pint of cheese curds (we substituted Cowgirl Creamery Fromage Blanc, but you could probably also use strained cottage cheese)

• 4 eggs (2 whole eggs + yolks from 2 others)

• Nutmeg to taste

Use a fork to mix the cheese curds with the flour, the eggs, sugar, and the nutmeg. Spoon them onto a buttered griddle.

We tried three different thicknesses, spreading the batter in the griddle to achieve different consistencies. We classified the resulting cakes as thick, medium, and thin — with thin meaning really quite thin. Here’s thick:

Here’s medium:

The thick and medium tasted a tad gummy; we vote for the slightly crisp texture of the thinnest cake:

And serve!

Curd cakes, it turns out, taste like surprisingly cheesy pancakes. After stuffing our faces, we got back to the question of whether curd cakes were classy. Delicious, yes. But high society? Maybe not? We speculated that curd cakes were downstairs fare, maybe the sort of dessert that Bates and Anna would have cooed over as they fell in love.

But we weren’t sure. We hunted around and found a 1597 Puritan cookbook called The Good Huswifes Handmaide for the Kitchin that offers the following recipe for “Curde Frittors”:

Take the yolks of ten Egs, and breake them in a pan, and put to them one handfull Curds and one handful of fine flower, and straine them all together, and make batter, and if it be not thicke enough, put more Curdes in it, and salt to it. Then set it on the fire in a frying panne, with such stuffe as ye will fry them with, and when it is hot, with a ladle take part of your batter, and put of it into your panne, and let it run as smal as you can, and stir then with a sticke and turne them with a scummer, and when they be faire and yellow fryed, take them out, and cast Sugar upon them, and serve them foorth.

(The Good Huswife also features “A Tarte to prouoke courage either in man or Woman,” but that’s a story for another day.)

Anyway, curd fritters seemed close enough to curd cakes and it all seemed nice and low-key, but then we also stumbled across this recipe from a book by Elizabeth Grey, Countess of Kent, which offers the following recipe for curd cakes:

“Take a pint of Curds, four Eggs, take out two of the whites, put in some Sugar, a little Nutmeg, and a little flour, stir them well together, and drop them in, and fry them with a little Butter.”

“COPYCAT,” we can say of the Countess, and did.

That cookbook, incidentally, is called “A choice manual of rare and select secrets in physic and chirurgery” and the title continues in this vein for some time before concluding with “as also most exquisite ways of preserving, conserving, candying, &c.;” It was published after the Countess’ death in 1653, and doesn’t it just drip with snobby self-praise? Exquisite! Choice! Select! Rare! And yet the Countess’ recipe is materially identical to the Puritan’s, proving once and for all that aristocracy is a sham and that curd cakes, like the Crawleys, transcend class distinctions.

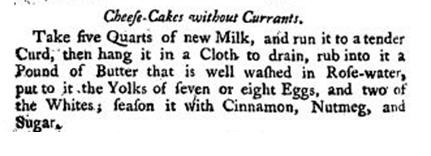

In 1755, just as George the future Mad King was about to turn seventeen (never suspecting the coming revolution), Sarah Jackson published her “The director: or, young women’s best companion,” which sets out the following recipe for Curd Cheese-Cakes:

Coming across this, we exchanged rich looks. Hidden within our simple curd cake were — or so we began to hope — the deliquescent delights of cheesecake! The Ultimate Democratizer. The kinship may be obvious to those reading this account, but we never suspected our interest in curd would take this curious and congenial turn. Cheese. Curd. Cake!

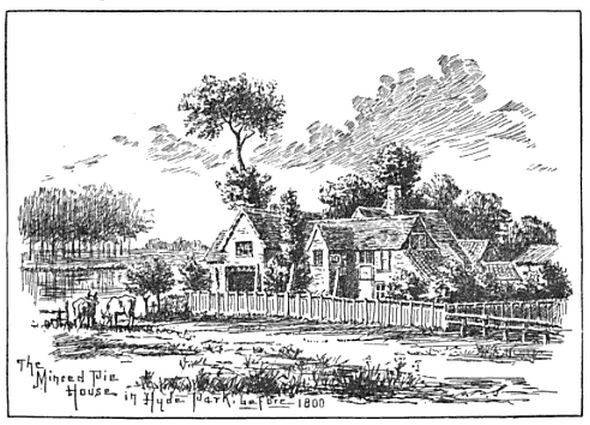

Our researches brought us across one other interesting historic tidbit: The existence, from the 17th century till the middle of the 19th, of a Cheesecake House. It had its start as one of the earlier buildings open to the public in Hyde Park. Variously known as ‘Grave Maurice’s head,’ Price’s Lodge, the Moated House, or just ‘The Lodge,’ it eventually became known as ‘the Cheesecake House’ because of the good cheesecake served there. By Queen Anne’s time it was more generally called ‘the Cake House’ or ‘Mince-pie House,’ “and according to the fashion which still continued to prevail, the beaux and belles used to go there to refresh themselves” with — and here was a happy thing — syllabub and cheesecake. They did in fact go together. Just like Sybil Crawley and her Irish chauffeur.

Previously in 17th-Century Delights: Whipp’d Syllabub

Gina Patnaik is a onetime chef and current Ph.D. candidate in English at UC-Berkeley. Lili Loofbourow is a writer in Oakland. She writes at Dear Television and over here.