After The End Of Men

After The End Of Men

by Mallory Ortberg

We were warned about The End of Men — but we did not listen. When the time came, the young were the first to go, dropping their toys and books and tools in the schoolyards, the fields, the trails running steady toward the horizon. The fathers and the aged followed shortly thereafter. It happened always with the same progression: the blank and curious light behind the eyes, the stiff and frozen gait, and then the hurried, silent exit. Women who were previously pregnant with sons ended up birthing stubs of candles, handkerchiefs, even fountain pens. Within a matter of weeks, the men had abandoned social life altogether, and no amount of hunting or pleading could bring them back.

This was all largely before my time, of course. My recollections are a patchwork of faded memories, snatches of poetry, my grandmother’s tales by the fireside. Since the days of my girlhood, all talk has been girl talk; all time was girls’ time; all nights were ladies’ nights.

I pen this late at night with the Sisters asleep around me. I do not know if anyone will find this confession, nor what good they might do once it has been read. The hour grows late — it may be too late — but I will write, and wait, and hope.

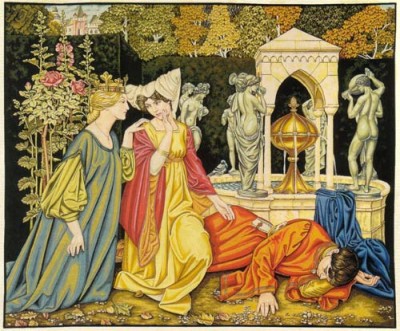

Before The End, men were plentiful. Not as plentiful as they had been in the Elder Times — the high days of song — but there were men nonetheless. They roamed the grassy interior of the continent in vast and gentle herds, pausing by our wells every summer during the Great Migration. The first Sighting of Men was always cause for excitement in the hot, dull days, and at the first sign of their approach we children would rush down to the water, screeching and laughing. We knew the rules: one may look upon a man, but one may not feed him or keep him. One may not touch a man; the others would turn on and cast out any one of them who had suffered the touch of a woman. The rejected ones would crawl dejectedly behind the herd, but, weak and dazed as they were, rarely survived more than a few dusty miles.

But that summer, that particular summer, I was down by the well at dusk fetching an extra bucket of water before prayers — when I saw him. The herds had passed through our village weeks ago. He must have been lost or cast out by his fellows. I’d never seen one alone before. At the first sound of my footsteps he leapt up from the stream, face smeared with dirt and tears and he looked at me. I know how it sounds and I know the Sisters would have mocked me roundly had I tried to tell them, but he looked at me and I saw something in his eyes that hot moonlit evening I’ve never been able to forget. He was so young. For a few moments we just stood there staring. I thought he might have been ready to speak — until the sound of a frog splashing into the river sent him running for the trees.

Later, when the herds were rounded up and decimated (and they were decimated, no matter what the Shepherd’s Council will try to tell you), I couldn’t stop thinking of that boy’s eyes. They called them Man Caves, the places they took them. Man Caves. As if any man could have survived in those mines.

I wonder, often, how long he lived. I wonder what finally dimmed then extinguished the light behind those eyes that stared at me on that grey mossy night, when I still wore the robes of a Ceremonial.

Now there are no men, and we speak not of them, except in these forbidden memoirs. The mines have long since been abandoned to whatever unspeakable crawling things first explored their nightmare passageways. Now there is no one left to speak for the days before we sinned, but I will go to my grave saying we should have suffered those men to live, with the memory of those eyes haunting me always.

Mallory Ortberg is a writer in the Bay Area. Her work has also appeared on The Hairpin, Slacktory and Ecosalon; Kate McKean’s her agent.