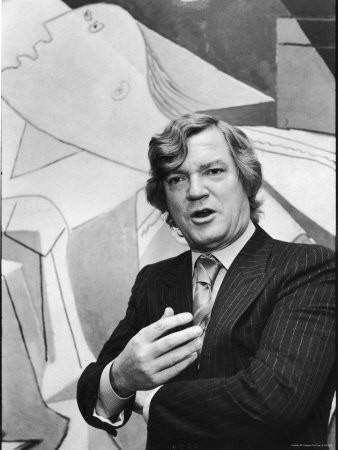

Robert Hughes, 1938-2012

The Australian art critic and historian Robert Studley Forrest Hughes died yesterday at the age of just 74. He’d withstood such a lot, coming back after weeks in a coma following a terrible car accident in Australia in 1999. I thought he was so strong that he would still live to be 100. Part of his name, even, was ‘Studley’! And that is just what he was.

What is the best thing Hughes ever did? How to choose from this embarrassment of riches? The obvious answer would be his stately, gorgeously comprehensive history of the convict settlement of Australia, The Fatal Shore (1987). Equally obvious: the 1980 TV series “The Shock of the New,” which you can watch in its entirety online. This is the thing that brought him fame, and no wonder. It’s a marvel: a solid education in post-Impressionist modern art of the 20th century in the form of a luscious entertainment stretching over hours and hours; awareness, scholarship, wit, and a visual sensitivity matched for once by an equally sensitive sense of language, all delivered in a brisk, whip-smart, slightly clipped Anglo-Australian voice of enormous power and beauty.

But there was so much, much more.

There’s his art criticism in prose, as collected in part in Nothing If Not Critical; his sumptuously pleasurable book about Barcelona. There’s his fire-breathing political writing, notably the book The Culture of Complaint, an indispensable salvo fired in the culture wars. Hughes’s troubling and beautiful memoir, Things I Didn’t Know, would alone have been enough to secure his fame, and yet it’s one of his lesser works; it was reviewed by fellow Australian Clive James in one of the most beautiful reminiscences of one friend for another in modern letters. James and Hughes were at university together, and his memories have that indefinable intimacy possible only between those with a shared youth.

Among my generation of aesthetes, bohemians, proto-dropouts and incipient eternal students at Sydney University in the late 1950s, Robert Hughes was the golden boy. Still drawing and painting in those days, he wrote mainly as a sideline, but his sideline ran rings around his contemporaries, and his good looks and coruscating enthusiasm seemed heaven-sent, as if the mischievous gods had parked a love-child on us just so they could watch the storm of envy.

No lie, he was good-looking too, brilliant, accomplished. From a patrician Catholic family. But what really got James into a companionable tizz was Hughes’ success as a lover.

He admits that he had a good memory, for example, but should have said that it was photographic. He admits that he was active as an illustrator for the student magazines and stage productions but should have said that his speed and skill left us flabbergasted. He admits that he flourished as a student journalist but fails to add that the downtown editors stormed the university walls and kidnapped him. He admits that he did all right with the girls but forgets to say — ah, this is the unforgivable malfeasance — that he cut a swathe without even trying.

Brenda, a British ballerina from the touring Royal Ballet, at least gets a mention. I remember her: she was so graceful that you went on seeing her with your eyes closed. The gorgeous Australian actress and future television star Noeline Brown gets a longer mention, as well she might: I knew Hughes well enough to see him in her company many times, and there wasn’t an occasion when I didn’t whimper from envy. But there was another one, called Barbara, who looked as if she spent her spare time standing in a sea-shell for Botticelli, and she doesn’t even get a sentence.

But let’s not forget to have the rough with the smooth. Hughes wasn’t the least bit nice. Oh no. He was downright vicious, mean as a snake, and hilarious. So mean that you would feel guilty from laughing. The drubbing he gave Julian Schnabel for daring to write a memoir! “The unlived life is not worth examining.” And Jeff Koons! “Koons is the baby to Andy Warhol’s Rosemary. He has done for narcissism what Michael Milken did for the junk bond.”

My favorite of Hughes’s many hatchet jobs is “The Patron Saint of Neo-Pop” [paywall], a positively lethal NYRB poison-pen essay he wrote about Jean Baudrillard, the French writer who’d arrived at the intersection of fashionable art criticism and poststructuralism in the 1980s. Oh man. The poor wretch didn’t stand a chance.

Jargon, native or imported, is always with us; and in America, both academe and the art world prefer the French kind, an impenetrable prophylactic against understanding. We are now surfeited with mini-Lacans and mock-Foucaults. To write straightforward prose, lucid and open to comprehension, using common language, is to lose face. You do not make your mark unless you add something to the lake of jargon whose waters (bottled for export to the States) well up between Nanterre and the Sorbonne and to whose marshy verge the bleating flocks of poststructuralists go each night to drink.

At a time when a lot of ink is being spilled about the excess of “niceness” infesting cultural discourse, criticism and journalism, Hughes’s entire and total not-niceness comes as a bracing restorative. Though he really took it way way too far, sometimes, for the most part the formidable scholar in Hughes — meticulous, exact, unflinching — tempered his anger into a searing brilliance. And as mighty as his instrument could be — I thought of him as a Hephaestean writer, in a lot of ways — he could also wield it with all the Apollonian delicacy in the world.

Claud Cockburn, in one of his volumes of autobiography, recounts how as a reporter in the thirties he had gone to interview a big American hot-gospeler who had crossed the Atlantic to convert England. Cockburn pressed this mild and hearty soul for a description of God. What was his ideated form of the deity? The evangelist allowed that he never imagined God as an old man with a beard in the sky. “My conception of Him,” he told the rporter, “is something like a great, oblong, luminous blur.”

That was all Rothko had, by way of religious imagery. In anguish, the blur was dark; in respose and happiness, suffused with the peachiest and most delicately tuned colors. In their similarity to landscape, the august blurs stacked up the canvas often connect Rothko’s work to an older American tradition, that of Luminist painters such a s Kensett and Heade: horizon, mountain and light seen as God’s handiwork, the Great Church of Nature. […] One does not read Rothko’s tiers and veils of paint primarily as form: they are vehicles for color sensation, exquisitely set forth in a technique that descends from Rothko’s watercolors of the 1940s — wash upon wash of thinned pigment soaked into the surface, filtering the light.

Such a blow, that he is gone. Adieu, Maître.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.