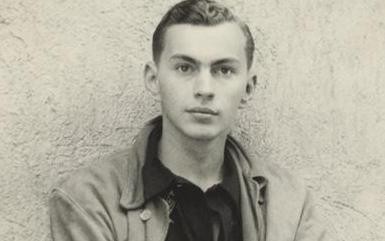

Gore Vidal, 1925-2012

Gore Vidal despised the New York Times through and through and would barely have stomached his obituary in that paper today, as credit-giving and realistic and praising as it is. Charles McGrath notes some of the impetus for this hatred in the obituary itself: the fallout from his 1948 book The City and the Pillar: “Mr. Vidal later claimed that the literary and critical establishment, The New York Times especially, had blacklisted him because of the book, and he may have been right.” Oh, that “may have” would have done him in.

Writing in the New York Times in 1977 — nearly thirty years after The City and the Pillar! — the very liberal Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, the now-retired watchkeeper of the end of an era of literature — reviewed Vidal’s collection of mid-70s essays. He found Vidal’s essays “seductive” (hmm) but found that Vidal had a simple explanation for everything, so what might be the simple explanation for Vidal?

So we are left to speculate over the psychological implications here, and to conclude that Mr. Vidal’s animus toward everything from West Point to the American Establishment — not to speak of academicians, who are, after all, instructors — boils down to an unresolved hostility toward his father, further evidence of which, some would argue, is Mr. Vidal’s cheerfully admitted homosexuality.

Lehmann-Haupt was in part using this as an example of the too-easy explanation — “simplistic, presumptuous and perhaps none of our damn business” — but there it is anyway.

Vidal wrote a letter to the editor which the Times declined to publish. The New York Review of Books published it instead:

This is quintessential New York Times reporting. First, it is ill-written, hence ill-edited. Second, it is inaccurate. Third, it is unintelligent in the vulgar Freudian way. There is no evidence of an “unresolved hostility” toward my father in the pages under review or elsewhere in my work. Quite the contrary. I quote from Two Sisters, a Novel in the form of a Memoir: “my father was the only man I ever entirely liked….” Nowhere in my writing have I “admitted” (“cheerfully” or dolefully) to homosexuality, or to heterosexuality. Even the dullest of mental therapists no longer accepts the proposition that cold-father-plus-clinging-mother-equals-fag-offspring.

These demurs to one side, I am grateful to your employee for so beautifully demonstrating in a single sentence so many of the reasons why The New York Times is a perennially bad newspaper.

Besides, as he discussed in 2007, it was his mother that he hated:

Q. You’ve written about how your parents had a bad marriage — is that where your general opposition to the institution comes from?

A. I think that’s where a lot of it started. When I looked at my mother, who was really one of the few people in my life that I hated, I thought, ‘Dear god, it’s marriage that is the culprit.’

Q. That’s quite something, to hate one’s mother.

A. Well, I adored my father. There he is, in that picture over there. The dark-haired guy. He was the greatest athlete in the history of American universities. Got a silver medal in the Olympic Games in Antwerp in 1920. A wonderful person. We knew each other for 43 years, we agreed on nothing and we never quarreled. Only men can do this. Women can’t.

To be held up, over and over again, over the course of decades, as both being merely troublesome because he is a faggot, from the Times all the way down to William F. Buckley, and to be counted as discreditable solely because he is a faggot, even as he never actually identified as such a thing: what could be more angry-making? Or a point of pride. In 1974:

I am proud to say that I am most disliked because for twenty-six years I have been in open rebellion against the heterosexual dictatorship in the United States. Fortunately, I have lived long enough to see the dictatorship start to collapse. I now hope to live long enough to see a sexual democracy in America. I deserve at least a statue in Dupont Circle — along with Dr. Kinsey.

But his real complaint regarding the Times and the American media had far less to do with that kind of stupidity; instead it had to do with the media’s complicity in the great selling of America’s advertisements for itself. As he said in 2006:

Q: You’re a veteran of World War II, the so-called good war. Would you recommend to a young person a career in the armed forces in the United States?

A: No, but I would suggest Canada or New Zealand as a possible place to go until we are rid of our warmongers. We’ve never had a government like this. The United States has done wicked things in the past to other countries but never on such a scale and never in such an existentialist way. It’s as though we are evil. We strike first. We’ll destroy you. This is an eternal war against terrorism. It’s like a war against dandruff. There’s no such thing as a war against terrorism. It’s idiotic. These are slogans. These are lies. It’s advertising, which is the only art form we ever invented and developed.

But our media has collapsed. They’ve questioned no one. One of the reasons Bush and Cheney are so daring is that they know there’s nobody to stop them. Nobody is going to write a story that says this is not a war, only Congress can declare war. And you can only have a war with another country. You can’t have a war with bad temper or a war against paranoids. Nothing makes any sense, and the people are getting very confused. The people are not stupid, but they are totally misinformed.

And as he wrote in one of his memoirs, published in 2006.

By last year, it could seem like he’d made a kind of peace with all this mess, but viewed another way, he’d actually won on both these fronts. The “heterosexual dictatorship” is in collapse, and the old print media’s particular kind of stenography and passive-”objective” engagement in the news of the day is widely considered suspect. His point of view prevailed. To an interviewer in 2011:

Newspapers have always been lousy in America, but then it could be said that the whole country’s been lousy, so who am I to complain about the general condition? Then again, it’s my job: to complain about the general condition.