Common People: Class And The 80s

Common People: Class And The 80s

by James McGirk

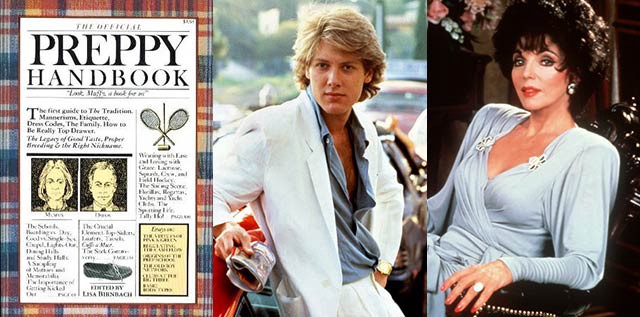

In the 1970s it was unusual to see wealthy families on television. The Jeffersons with their deluxe apartment in the sky, the occasional rich couple flitting over to “Fantasy Island” or booking a cruise on “The Love Boat” — these were the exceptions. But as the economy accelerated, mass culture was suddenly inundated with images of affluence. The wave hit around 1981, as the economy slowly recovered from the stagnant wages and inflation of the 1970s. Rabbit Angstrom, John Updike’s scampering everyman, began to make serious money on his appreciating property and selling Toyotas on his father-in-law’s lot in Rabbit is Rich; Joan Collins joined the cast of “Dynasty” as the splendid and venomous Alexis; and the second edition of The Official Preppy Handbook came out, gently mocking but also instructing a peculiar subculture of well-coiffed, pastel-hue wearing teenagers who wanted to look as if they summered on Cape Cod and worked on Wall Street.

Blotchy and imperfect of a reflection of us as it may be, mass media mirrors our desires. And as the Baby Boomers sloughed disco duds and snipped locks of graying hippie hair, they wanted to know, once more, who they were and what they were becoming. They couldn’t just become their parents. The Boomers were nothing like their mothers and fathers. They had had the Pill; they had seen men walk on the moon; there had been Watergate and oil cartels and Vietnam. So much had happened to them. So much had changed. And then there was this other peculiar thing happening to them. All of a sudden, not all, but many Baby Boomers — especially the brainier, college-educated ones who hadn’t gone off to Vietnam or scorched their brains with angel dust and laboratory acid — were getting rich. How could you possibly integrate all of this knowledge into a normal, upwardly mobile lifestyle? They didn’t know what to do. So someone had to tell them.

In 1983, two codices were released, Paul Fussell’s Class: A Guide Through the American Status System and P.J. O’Rourke’s Modern Manners. Together, these ur-texts of 80s yuppie-dom anticipate some of the most peculiar quirks of contemporary American life, namely our increasingly calcified class system, and the ways in which our upper classes have appropriated the styles and mannerisms of artists, writers and other bohemian outlaws in the guise of personal expression.

The Upper-Middle-Class Cats That Are Named Spinoza

Paul Fussell’s book is a peculiar hybrid form. Meticulously researched, it was laid out like a scholarly monograph (which makes sense given that its author was an English professor at the University of Pennsylvania). But there are cartoons illustrating Fussell’s points and a rate-your-own-social-class-by-looking-at-the-objects-in your-living-room test at the end. In contrast to his excruciatingly graphic, National Book Award-winning The Great War and Modern Memory, published eight years before, Fussell seems to be having fun with Class. His prose moves like quicksilver as he exposes and then ridicules America’s caste system, toppling one putrescent institution after another.

Paul Fussell begins by laying out a problem. “Although most Americans can sense that they live within an extremely complicated system of social classes and suspect much of what is thought and done here is prompted by considerations of status, the subject has remained murky. And always touchy. You can outrage people today simply by mentioning social class, very much the way, sipping tea among aspidistras a century ago, you could silence a party by adverting too openly to sex.”

He then breaks America’s class system down into nine categories.

At the very top, are the aloof “top out-of-sight” who live off ancient, inherited money and need never work; then come the upper class who may have inherited a lot, but earn a lot too, as bank presidents or financiers or part-time employees of art galleries. Beneath them are the upper-middles, high-earning professionals like doctors, executives and corporate lawyers who “like to show off their education by naming their cats Spinoza, Clytemnestra and Candide.”

Most people in 1983 (“if you innocently credit people’s descriptions of their status,” says Fussell) belonged to the middle class, which is “distinguishable more by its earnestness and psychic insecurity than its middle income… The middle class is the place where table manners assume an awful importance and where net curtains flourish to conceal activities like hiding the salam[i] (a phrase no middle-class person would indulge in surely, the fatuous making love is the middle-class equivalent.)” The middle class were salesmen no matter what their jobs were, in a constant state of status panic, clawing their way up the corporate ladder, subscribing to magazines like the New Yorker to acquire the trappings of the upper class, perpetually terrified of losing their jobs, forced to constantly worry about how they might appear to their superiors — even at home, where they scrutinized their wives and children for fear that an embarrassment might cost them their jobs.

Beneath the middle class are the three tiers of proletarians (high, middle and low). Prole jobs are often dangerous. Fussell quotes from Andrew Levinson’s The Working-Class Majority (1974) and asks his readers to imagine:

The universal outcry that would occur if every year several corporate headquarters routinely collapsed like mines, crushing sixty or seventy executives. Or suppose that all banks were filled with an invisible noxious dust that constantly produced cancer in managers, clerks, and tellers. Finally, try to imagine the horror… if thousands of university professors were deafened every year, or lost fingers, hands or sometimes eyes, while on the job.

There are gentler ways to distinguish parse proles from the rest of the population. “One way to ascertain whether a person is middle-class or high-prole is to apply a principle that the wider the difference between one’s working clothes and one’s ‘best,’ the lower the class.” High proles are the carpenters and the contractors, the mailmen and truck drivers. More often than not their jobs involve skill. They have a lot of freedom and are generally happy. The lower tiers of prole, are subject to the authority of another, of a ‘click,’ an archaic pejorative term for a foreman or someone who “runs things.” The lowest level of prole is “identifiable by the gross uncertainty of his employment,” and includes illegal aliens and migrant workers.

Beneath the proletariat are the destitute, who live wholly on welfare and the bottom-out-of-sight, which is when “you stay all day in your welfare room or contriving to get taken into an institution, whether charitable or correctional doesn’t matter much.”

Money is not perfectly correlated with status, according to Fussell. Certainly it takes a lot to ascend to the highest rungs of society, but once you arrive, the amount you have matters less and less. Things like comportment and behavior become increasingly important. Above all, you don’t want to stick out, or, if you do, it has to be done in the correct manner. “We can say of [the very topmost classes’] expectations of their children what Douglas Sutherland says of the English gentleman’s: ‘his offspring are expected to conform in all things, and academic brilliance is not an acceptable deviation from the normal.’”

Beneath the uppermost ranks, Americans compete ferociously for status and distinction. “In the absence of a system of hereditary ranks and titles, without a tradition of honors conferred by a monarch, and with no well-known status ladder even of high-class regiments to confer various degrees of cachet, Americans have had to depend for their mechanism of snobbery far more than other peoples on their college and university hierarchy.” This is a particularly pernicious vehicle for transmitting inequality, because, while there seems to be no difference between a bachelor’s degree at one college and another, to a snobby upper-middle-class employer that might pay a healthy wage, even in 1983, there was a chasm of difference between a degree from a place like Swarthmore and a place like Carlow College, Pittsburgh (to borrow Fussell’s examples.) Of course if you were truly upper class, you would have already “gone away” to a decent prep school. Those who wait until college to leave home are already in “class arrears.”

The French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu described good taste and manners as being conditioned into the Parisian elite, rather than as hard-won traits or some innate superiority to the lower echelons of French society. According to Mark Greif, Bourdieu surveyed thousands of Frenchmen and found eerie correspondences within social classes. Artists and college professors unanimously agreed that “a beautiful photo could be made of a car crash,” unlike any other social group. White-collar workers “defined themselves by their proclivity to eat light foods.” Taste and manners really are nothing more than an embodiment of wealth and status, a subtle collection of habits and mannerisms that signal to others that you belong or if you don’t, become a million little ways to trip you up and detonate your [beastly] class aspirations.

THE SOCIETY OF Xs

Paul Fussell identifies a way out of what he clearly saw as an appalling imbroglio. He devotes the last chapter of Class, “The X Way Out,” to a hypothetical tenth category of misfits and aliens he calls “X.”

“What class are we in and what do we think about our entrapment there?” asks Fussell, reflecting on the peculiar sensitivity of Kingsley Amis’ poem “Aberdarcy: The Main Square.” Here his prose shifts from slightly sour snark to something almost jaunty, as he describes a class of writers and artists and intellectuals who lurk at the fringes, coming and going the way that Huckleberry Finn did, free to drift through society because they are able to see through the pretense of it all. He ends with an exhortation, inviting his readers to join him: “The society of Xs is not large at the moment. It could be larger, for many can join who’ve not yet understood that they have received an invitation.”

P. J. O’Rourke is under no such illusion, however; he sees through the pretense of class X’s affectation of irony and art. Modern Manners is written from a self-consciously middle class, even conservative, perspective. What O’Rourke is calling ‘modernity,’ the appurtenances of which include the drugs, the television, the shallow affect of fame and crass culture and easy sex, are really nothing more than the residual Dionysian impulses of the Baby Boomers, particularly that emerging class of quasi-creatives Paul Fussell might have called Xs.

Good manners can replace intellect by providing a set of memorized responses to almost any situation in life. Memorized responses eliminate the need for thought. Thought is not a very worthwhile pastime anyway. Thinking allows the brain, an inert and mushy organ, to exert unfair domination over more sturdy and active body parts such as the muscles, the digestive system and other parts of the body you can have a lot of thoughtless fun with.

O’Rourke’s book is of a more abrasive and snide sort of humor than Fussell’s. Modern Manners is raucous and snickering, constructed from squibs and short sentences that snap. It is the kind of book that people used to stow in their bathrooms for the entertainment of guests. The book is a tongue-in-cheek primer that shows its reader how to go about camouflaging him or herself with good manners. “Just as cleanliness becomes more important at moments when godliness is not possible, so manners come to the fore when more august forms of authority collapse. The world is going to hell. All we can do is look good on the trip.” O’Rourke lays out proper “Regurgitation Courtesy” (don’t eat foods that might clash) and advises how to properly play with one’s food, which “must be done exactly right or it will lead to social disaster.”

But perhaps his most venomous attack on self-consciously arty people is the chapter devoted to “Creating a Persona: The New Polite You.” The key is to become interesting, and to do this you must adopt a genealogical history that “will give dignity to a rich person, breeding to poor one, and, if used with wit and style, make even a middle-class person socially acceptable.” Your new family contains invented characters who are exotic, blue-blooded, famous, tainted with an awful secret, venerable, artistic, sinful, rich, bad and trendy plus “three optional subtypes, mysterious, crazy and tragically dead.” The implication, of course, is that being interesting is just as affected and fraudulent as anything else.

CREATIVE CLASSING

Nearly 30 years later, P.J. O’Rourke’s observation that interesting people can be as repugnant as anyone else has been absolutely vindicated.

The self-consciously creative class has continued to expand, particularly as college education has grown more common and information technology has increased the demand for jobs that are knowledge-based and/or ostensibly creative — advertising, graphic design, content production, analysis, etc. In fact, being creative — at the very least, as a consumer — has now become a symbol of the elite, at least according to a recent opinion piece in The New York Times written by sociology professor Shamus Khan.

“Today’s elite are not ‘highbrow snobs,’” proclaims Khan, who spent year studying elite prep-school students at St. Paul’s in New Hampshire. “They are ‘cultural omnivores.’” The elite once affected only the most highbrow of tastes, attending the opera, collecting European painters, playing polo and teaching their horses how to dance, etc. But that isn’t enough anymore. “If elites have a culture today, it is a culture of individual self-cultivation. Their rhetoric emphasizes such individualism and the talents required to ‘make it.’”

Consider how similar the concept of ‘self-cultivation’ sounds to this sally from P.J. O’Rourke’s “Creating a Persona: The Polite You” chapter:

In order to know how to act you must first know who you are… You, for instance, are probably no one in particular. This is because of your dull family. Boring people with humdrum backgrounds were bound to raise a very ordinary you… This is a grim statement and, fortunately, a false one… You can modify your family to suit your needs for an interesting background and alter all of your relatives so that you will have a fascinating personality from them… by the simple expedient of lying.

Substitute an appropriately eclectic taste for a dull family, in other words; look at the self-consciously ‘interesting’ lives of Xs, and you see Khan’s point that “cultural ominivorousness” has simply created another, even more obtuse layer of exclusion. After all, it takes time, money and education (not to mention a healthy sense of entitlement) to be able to proclaim a simultaneous appreciation for a $1,500 meal at Masa and a Papaya Dog hotdog, or to own (and sincerely enjoy) both opera and rap music records (to use Khan’s examples.)

“Omnivorousness is part of a much broader trend in the behavior of our elite, one that embraces diversity,” writes Khan. “[Yet] paradoxically the very openness and capaciousness that they so warmly embrace — their omnivorousness — helps define them as culturally different from the rest. And they deploy that cultural difference to suggest that the inequality and immobility in our society is deserved rather than inherited.”

Remember all of those rotten extra-curricular activities your school was trying to make you do for your college application? It was all about creating a compelling narrative about yourself, a way to standout from your peers. Of course the only people who could really standout were the ones who could afford not to work at McDonald’s and started peewee charities and ran half marathons in their spare time. That is how you get into a good college and that in turn is how you worm your way into the upper middle class. (Any higher than that will take inherited money.) The system is rigged. It always has been and always will be.

BLAME THE BABY BOOMERS

The perception of being rich and the rich being visible in popular culture has since gone through various permutations.

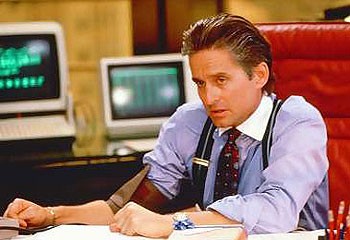

To return to the vast of wave images that struck in the 1980s, Modern Manners and Class were published in 1983. After that came Robin Leach’s rather grating “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous” and Jay McInerney’s Bright Lights, Big City in 1984. The following years (1985 and ’86) brought Bret Easton Ellis’ Less Than Zero and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (and the wrecked Ferrari). The crest came in 1987, when Andy Warhol died and Tom Wolfe published The Bonfire of the Vanities, and the Wall Street movie with greedy Gordon Gekko came out, and then it all began to ebb away after Black Monday, also in 1987, when the stock market lost a quarter of its value in a single day, and zapped all those swank industries that had grown to serve the wealthy.

After that we recoiled from the audacious and tacky 1980s in the early 1990s, and then re-discovered the joys of ostentatious wealth in late 90s and early aughts before the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 and our current lurch into populist sentiment. Being really rich probably won’t be cool again until the next bubble. But, no matter how creative and classy we might think we are these days, inequality is growing and our class system is increasingly calcified in place.

Those of us who cringe at the thought of offending our bosses and slipping off the career track and being unable to pay interest on our student loans are just as trapped and scared and middle class as the legions of company men Paul Fussell described being shuffled around the country in 1983.

Perhaps the only thing that has really changed since the early 1980s has been the disappearance of the true X outlaws, the teenage subcultures, the real subcultures where working-class people removed themselves from society to devote themselves to living an aesthetic: from the 19th-century bohemian renegades to the Beatniks to the last permutations of goth and punk in the 90s. These days truly committed freaks and weirdos are discovered and plundered by marketers at such a fearsome rate that they hardly get a chance to exist before they are smeared all over the Internet and tweeted about.

So nowadays, when we peer into the cultural abyss, there is no alternative lurking beside it; there is just this seething mass, this infinite mass of shitty little tweaks we can make to our online personas. And the Boomers are hovering along side of us, Liking Viagra on Facebook and watching their 401Ks drain slowly away.

James McGirk claims to be posh but never ever seems to have any money.