The Perils Of Storytelling As A Stranger: A Chat With Tom Scocca

The Perils Of Storytelling As A Stranger: A Chat With Tom Scocca

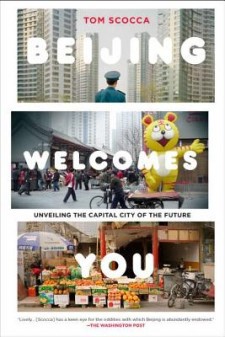

Tom Scocca’s Beijing Welcomes You: Unveiling the Capital City of the Future has just come out in paperback. This distinctive American’s-eye-view of China’s capital is bracingly cerebral without didacticism, intimate and touching without the slightest trace of “self-realization.” I loved it.

Maria Bustillos: There is so much I want to know about your book, and about China. How long has it been since you were last there? How has the book been received? How old is [your son] Mack, [who was born in China], now?

Tom Scocca: We haven’t been back since I was doing the epilogue, in May 2010. The book’s been received pretty well, I think. Or the people who don’t like it haven’t sought me out to say so, at least.

Mack is now 5, and an older brother.

MB: Congratulations!!! Always nice to have a baby about.

So, what struck me most about Beijing Welcomes You when I first read it was the matter of “foreignness,” which you examined from a number of perspectives. I’ve had occasion to think about these aspects of it often and often.

The Mike Daisey business, for example; it was almost as if Daisey had never left the States; he took all his first-world perspectives with him to China, and brought them back undisturbed. Stayed “foreign” himself.

TS: The Daisey thing was offensively white in many different ways.

MB: Offensively “white” or offensively “American”? Or offensively “PC”?

TS: Offensively White American.

The writer who cooks up composite characters and adds vivid details to their lives is condescending to them, because they’re not real people.

MB: He had an agenda that way superseded his interest in engaging with anyone. They were actors in a drama he felt it “important” to produce.

TS: Right. And his story is more important than any other (more accurate) stories anyone else might tell.

MB: Yeah. Rob Schmitz, the NPR guy who broke the story, gave a very nuanced account. I thought he was generous to Daisey, understanding the motives but flatly rejecting the tactics.

TS: Another irritating aspect to Daisey — the message that lamestream journalists weren’t able to get or handle the truth, but he could saunter right up to the factory gates and blow the whole thing wide open. Powered only by his innocence.

I mean, look, I’m not a China correspondent. That’s sort of a central part of the book.

MB: It was remarkable how Schmitz popped that bubble so easily. Also, the thing about you is that you are really the anti-Daisey in every way I can think of. Your book is effectively about getting your imagination (and the reader’s) over to the “other side.”

TS: Well, Daisey forgot that his translator was a real person. Who could ever track down one particular Chinese person in China? How could you possibly check his stories? No other white people were there! Therefore he himself was the only witness.

TS: It’s a basic premise of propagandistic Chinese nationalism that Western reporters tell lies about China to conform to their preordained storylines. So next time someone writes a story that genuinely shows abuses, the Chinese will point to Daisey.

MB: In addition to being a basic premise of Chinese propaganda, though, that’s an accurate assessment, right? This is almost inevitable for anyone, from any country; you’re stuck seeing things using the necessarily limited understanding you have.

I talked with Emmett Carson, who runs the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, a few months back, and he is pretty firm on the big-picture upside of Chinese industrial development. I felt the same way when I used to be a product developer traveling over there, but now I’m more ambivalent. I would love to know what you think about it.

TS: The question of the upside of Chinese industrial development feeds into a question I try to deal with some in the book, which is the scalability of our Western material standards of the good life.

TS: China argues, impeccably from a fairness standpoint, that Western countries got rich by deforesting and polluting and otherwise ravaging their environments, and that it’s hypocritical for us to criticize them for this ugly and toxic step along their own road to prosperity.

MB: This was one part of your argument that lost me, a bit. Not-impeccable for two reasons: 1) there is new, increased awareness of the ultimate cost of this kind of “prosperity” and 2) the vast difference in scale between the two projects.

TS: That’s why I specified “from a fairness standpoint.”

MB: (Also, the good life? Or the not-so-great life. So weird to me how nobody ever even tries to think of alternatives, just this one lame trajectory.)

TS: We are, unquestionably, asking China not to do what we did. Even though it worked for us.

But part of the reason we are asking that is not that we wish to see China remain relatively backward and weak, but that, as you say, we’ve figured out that despoiling the environment is a bad idea, and it’s especially bad and dangerous if the environment being despoiled is the size of China’s (which is to say: a measurably large chunk of the world’s).

Yet, you know, we’re not dialing down our own standard of living to share some of that with the Chinese.

MB: In effect that’s exactly we’re doing, though. That’s the argument that Emmet Carson (an economist, by training) and many other observers are making. If only because we’re the chief enablers of China’s rapid industrialization, as high-volume importers and also because US firms run so many Chinese factories. There’s a school of thought that says our standards must “fall” if everyone else’s are to “rise.”

And this is clearly happening now, as the direct result of sending so much of our manufacturing to Asia: sharing some of our “prosperity.”

TS: Beijing is being destroyed by passenger cars. Roads are impassable, the car-borne pollution is choking — but still four-fifths of Beijingers don’t have personal automobiles.

So are we going to end up in a world where Americans and Chinese people have the same number of passenger cars per capita?

MB: Clearly not, we’ll all croak first, right? Shouldn’t we all just figure out something else that would be more fun, more elegant, less harmful, more pleasant? For Chinese people, for Americans?

TS: Unless Americans start driving many fewer cars per person.

MB: Or unless cars themselves change. If we cared enough to sort it out together, maybe we could make cars that would go ten thousand miles on a gallon of gas. Those who stand to benefit from preventing that, will prevent it.

MB: The times I spent working in Taiwan and China, I found it hypnotically weird that everyone was my height and that I was the only white (ish) person for days. This is unnerving to someone from LA.

TS: When was that?

MB: Early to mid-90s; mostly in and near Taipei, but some time on the mainland. One time after I’d been there for a matter of weeks, I finally saw a black guy in the street and practically burst into tears of homesickness and happiness.

TS: Only out in the provinces did I have that lone-white-person feeling. Like down in the sticks in Yunnan, schoolchildren followed me down the street in curiosity.

MB: Dang.

TS: I mean, there were plenty of times in Beijing that I was the only white person around. But not all day long.

MB: This I’ve been dying to ask you, because I have never understood it even a little bit. Please explain your understanding of the economic/political tensions between Taiwan and China.

TS: Oh, lordy. Well, the thing normal American discourse is unclear on is that the Republic of China and the People’s Republic of China are reciprocally in agreement. It’s just whether the One True China has one renegade province or 31 renegade provinces.

(Provinces, autonomous regions, municipalities.)

MB: The individual guys who live and work there, e.g. who are agents or run factories, seem permanently nervous about their political situation — it seems precarious, but how, exactly? And if there is agreement, why?

TS: There’s a certain willingness to put up with the contradiction between those two points of view, even though to Americans it seems to be the very definition of a reason for armed hostilities.

Of all the dire predictions in the run-up to the 2008 Olympics, the one that seemed furthest off base was that the PRC might be emboldened to storm across the strait and subjugate Taiwan.

It doesn’t seem at all unimaginable that both sides will eventually converge on some sort of authoritarian plutocratic consensus. Or maybe democracy! But either way, it could work itself out without conquest.

NONFICTION VS. REPORTING

MB: Let’s get back to nonfiction. I found that a lot of the most compelling parts of your book are to do with intensely personal reactions to things: yelling at people to get in line, making soup for your baby, running the bureaucratic gantlet.

That seems like a big part of the reason Mike Daisey’s stage show got through to people: they want to hear stories about personal things. It makes the place come alive, you can ID as a reader, feel yourself in the place. Reports of your own lungs hurting move the reader in a much different way from just hearing about the air pollution in Beijing.

Please comment on the rightful place of the personal in “nonfiction” or “reporting.” (Sorry about the scare quotes, I just mean, “or whatever we want to call these things.”)

TS: It’s tricky. I’m not much of an oversharer, in general. Lots of first-person writing drives me up the wall. “Modern Love” is, to me, basically an ongoing crime against humanity. But first-person pronouns aren’t the same thing as rampaging authorial ego, necessarily.

MB:: I wouldn’t call you an oversharer, but you had best cop to a very intense degree of authorial intimacy with the reader (that is to say I am about to bawl right now, just thinking of your eulogy for your father, for example. And so many places in your book, as well.)

TS: Well, this book in particular is about being a subjective observer, with serious limits to my access to information, in an unfamiliar setting. I didn’t have any useful background understanding of Beijing; I had only the vaguest sense of how the city was even put together (Tian’anmen Square, ring roads, Forbidden City or something). I had almost no language skills, except pretty good mimetic handwriting for characters.

So I was coming into it unable to feign any sort of authority. The first sentence of the book is sort of my capitulation to that truth — that whatever I ended up understanding about this place and this time, I was going to have to build from the most idiotically basic premises. There are people out there who are comfortable unfurling blanket truths about What China Means or whatever. I set out to patch together a quilt. I think after a couple of years there, a lot of note-taking, and a childbirth, it ended up being kind of a large and thick quilt, but it was no use pretending it wasn’t made up of lots of scraps stitched together.

And my ignorance, from the outset, made me more or less the target audience for the story that China was trying to tell me (or show me).

TS: For starters, being functionally illiterate is a very unusual and bracing experience, for a writer.

MB: “Like a baby,” as David Foster Wallace said. I was practically insulted the first time that happened to me (in Brazil, when I was twelve.)

TS: And I don’t remember being a baby. I learned to read when my older brother did, so I basically have no memories of a time when I wasn’t able to take up written information. Till I got off the plane in Beijing, I mean.

MB: I remember being a baby. My sharpest memory of it is the horrific taste of the plastic seal on my mobile.

THE OVER-UNDER OF PARENTING

TS: One reason the Underparenting column declined in frequency — speaking of oversharing — is that there came a point when most of the good funny stories about Mack would have had to deal with his crazy, crazy precociousness.

MB: That’s just the thing: I don’t know you but I know so much about you, from your writing. It’s super personal. You love that little boy, for example. It is an emotion, it’s like a golden ball of light that comes from your heart right into the reader’s heart.

TS: Like it was mind-blowing and cute when I’d come into his room in the middle of the night and he’d have turned up the dimmer on his light and be asleep on the floor surrounded by open books.

MB: I have a lot of ambivalence about “reporting” that would exclude that.

TS: At AGE TWO. But it just feels like a terrible humblebrag to get into the complications of that stuff. Luckily, Dominic is a box of rocks.

MB: That’s the stuff!

TS: When Dominic runs into something painful or startling, his response is, “Huh! Interesting! Let me try that again and see what happened!”

MB: My godson is like that!! He is shaped like a small fire hydrant and rates about the same on the Mohs scale, also.

TS: All of which is teaching me that people who are judgmental about how other people’s babies act should probably hold their fire till they see how the rest of their babies turn out. The boys are just wired up totally differently.

MB: The part about Mack’s birth in your book is really haunting, really beautiful. It’s stayed with me. Do you guys speak Chinese at home?

TS: We speak principally English, sprinkled with Chinese. The Chinese part tends to be commands or endearments.

MB: This is interesting to me because I grew up in two languages myself, but because of my love of English, I became more “American,” because more Anglophone. Your character changes in a different language, don’t you find?

TS: It’s hard for me to judge, because I’m good at English but very bad at Chinese. So in Chinese I tend to say very conventional and agreeable things.

MB: Er yeah, that would make a marked change from your English, Mr. Scocca.

CHINA NOW

MB: In closing, I’ve been reading a lot of stories like this one lately, about the growing strength of China’s environmental movement.

MB: Expat journalists like Kaiser Kuo, do you know that guy? I am a fan. This keynote address he made to a group of college-bound Chinese high-school grads, many of whom were coming to North America for school, was very revealing. “Build bridges!” he said. “Resist the urge to be offended by some people’s attitudes about China.”

This is just exactly what we tell American kids about their home country, when they go abroad!

TS: Kaiser? Yeah, I know Kaiser. I went and saw his AC/DC tribute band in Beijing. The electricity kept blowing out.

MB: Oo! Were they any good?!

TS: They were. AC/DC isn’t my thing, but they were good at it.

MB: I am so thrilled to know this. He and Schmitz, I thought, seem very undeceived generally. Apparently they used to work together at ChinaNow.com.

The condition of the press in China seems a lot worse than ours, on the face of what we can see from here, but I constantly wonder whether we’re not just as anaesthetized and controlled in our own way. That Steve Almond piece in The Baffler about Jon Stewart really resonated, I thought.

TS: It sort of did, but I enjoyed Alex Pareene’s dismissal of it on Twitter, too.

MB: Oh my god. Furthermore, nobody is exactly following Steve Almond onto the ramparts either.

What is to be done?

TS: Try to write about the situation and see what happens, I guess.

Maria Bustillos is the author of Dorkismo and Act Like a Gentleman, Think Like a Woman.