How We Got So "Comfortable With That"

How We Got So “Comfortable With That”

by Jane Hu

“Comfortable” is a flexible term. Any one person’s threshold for comfort can differ from another’s. For the individual, comfort is relative: a heat wave in Edmonton, Canada, say, no longer agonizes after one has endured a heat wave in New York. When a person says “comfortable,” they often mean “pleasant.” Other times “comfortable” translates to just “bearable” or “satisfactory.” While the word “comfortable” doesn’t change, a person’s definition of it can, and usually does, with time — that is, with age and experience. It might happen gradually, incrementally, with constant comparisons between then and now. Comfort itself is relative, its meaning elastic.

The word “comfortable” has been thrown around since the Middle Ages, and the volleying shows no signs of letting up. English speakers have gotten perhaps even a little too comfortable with “comfortable,” with expressions such as “I’m not comfortable with that.” There’s something about “I’m not comfortable with that” that smacks of learned therapy talk — a polite way of talking about our feelings by talking about them obliquely. Or, really, not talking about them at all: “I’m not comfortable with that” is efficiently euphemistic — an efficient way of saying “I’m not comfortable discussing this.” I’m not comfortable with that can mean you disturb my sensibilities, or I feel vulnerable, or leave me alone. It all depends on what “that” is. The earliest employment of the phrase I can find makes it specific. Elvis says in 1957: “I’ll never feel comfortable taking a strong drink, and I’ll never feel easy smoking a cigarette. I just don’t think those things are right for me.” One’s comfort level can indeed change, though Elvis provides us with an especially unhappy example.

You’d think the earliest uses of “comfortable” would be in context of describing physical comfort, but the more metaphysical version of the term precedes the bodily one by at least 50 years. The OED finds the first written occurrence of “comfortable” in Richard Rolle’s religious text English Prose Treatises (circa 1340): “Sothely, Ihesu, desederabill es thi name, lufabyll and comfortabyll.” The phrase credits Jesus’s name as affording spiritual delight. Fifty-ish years later come the first descriptions of physical comfort, which often appear in association with medicines and drinks to aid the sick. For instance, the 1440–1500 Gesta Romanorum (a collection of anecdotes and tales gathered from that served as source material for works by Chaucer, Boccaccio, and Shakespeare) compares “wine comfortable” as “juice to the sick.” Of course, the two meanings, physical and spiritual, are not mutually exclusive: comfort of the body influences comfort of the being.

In regard to the language of comfort, little has changed from then until now (this is rarer than not when tracking the etymology of most Latin-cum-English words). The stability of “comfortable” is partly due to its interpretive expansiveness. The phrase “I’m not comfortable with that” we saw coming into use in the 50s with Elvis has grown since time. That kind of discomfort — about mental and moral unease — has become so definitively attached to the phrase “I’m not comfortable with that” that I have to wonder why, and where, and how?

“I’m not comfortable with that.” One hardly ever says this in reference to a mattress just tested. “I’m not comfortable with that.” See what I mean? The phrase harks back to the initial meaning of comfortable, except rather than spiritual unease, it suggests a more secularized psychological dissonance with a situation or idea. The notion of an “I” being uncomfortable with a “that” could only exist in the modern age, where “I” was seen as a holistic, cohesive, and stable self and “that” could be any abstract thing that the “I” imagines. That tests the integrity of the I. Mattresses, for instance, rarely threaten one’s psyche (though what one does on them might prompt one to employ, “I’m not comfortable with that”).

It makes sense that Henry James — the most delicate wielder of euphemism — would exhaust all the phrasings that involve metaphysical comfort. In The Tragic Muse (1890), “comfort” appears a total of 66 times. One example: “This enabled him to be generously sorry for his companion — if he were the reason of her being in any degree uncomfortable, and yet left him to enjoy some of the motions, not in themselves without grace, by which her discomfort was revealed.” Abstract, right?

A close corollary to “I’m not comfortable with that” — capturing similar connotations as well as a quality of slang — was “comfort level,” which seems to have entered the popular lexicon from the 70s onward. A William Safire language column titled, yup, “Find Your Comfort Level” examined why in 1988.

Safire begins his piece by calling “raising the comfort level” one of Jesse Jackson’s “favorite locutions”:

“It’s a mutual growth process,” said Presidential candidate Jesse Jackson of his appeal to white voters, “what I call ‘raising the comfort level.’”

As Jackson suggests, comfort levels can be adjusted. It requires some give and take, but one can eventually adjust to what might, at first, feel new and impossible. Safire proposes that Jackson’s use of “comfort level” exemplifies a change from prior meanings of the phrase:

He is not alone in the use of this soothing phrase. Business Week, reporting on the supersonic Concorde aircraft in 1975, wrote: ‘’Its comfort level is roughly similar to some of the smaller and older jets, although it is much quieter.’’ That sense of physical well-being is still widely used in travel writing, but the meaning has been extended in voguish prose to a relaxation of mental tension.

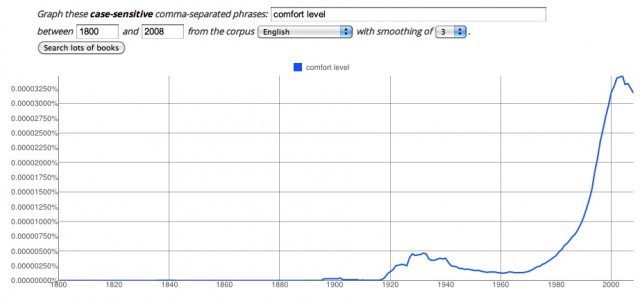

Again, the physical self and the mental psyche share their claim on usages of “comfortable.” The final sentence depicting “comfort level” might or might not have much to do with the “voguish prose…of mental tension” found in “I’m not comfortable with that.” But a search of “comfort level” in Google Ngrams shows that the expression originates at the same moment Elvis declared his discomfort toward drink and cigarettes.

Safire cites stockbrokers as the first to engage with “comfort level” — a twist, he suggests, on “sense of security.” The piece goes on to trace “comfort level” as it appears first in the financial and business districts, then on Madison Avenue and Toronto’s shopping district retailers, and later in politics. As “comfort level” is represented in the Times, the first articles where “comfort level” appears to describe a psychological baseline (rather than a physical one) begin in 1987. They’re also largely in relation to businesses, investments agencies, and the workplace. (Safire and I probably did the same search, except I had the Internet.)

The speculation throughout Safire’s piece is a titillating, and enabling, thing. Where I had a hunch that “I’m not comfortable with this” stemmed from the discourse of therapy sessions, Safire offers this about “comfort level”: “Where is it from? My first guess was psychiatric jargon.” One statement from the chairman of the Psychiatry Department at George Washing University, however, and this hypothesis is off the table. Safire concludes that “comfort level” derives from “climate control”:

I remember Joe Frederick, president of Long Island’s Sheet Metal Workers Local Union No. 55, using the phrase frequently in the 1950’s: “You can’t get a consistent comfort level without warm air heating.”

Safire does not attempt to make a connection between “I’m not comfortable with this” and “comfort level.” I assumed an association between the two, but would he have? Impossible to tell from his article. And does it really matter, finally, if we pinpoint whether “comfort level” came from psychiatric discourse or “climate control”? From the sporadic guesses and clues Safire tugs into his argument, it doesn’t really feel like he all that much cares about claiming or confirming the phrase’s ultimate origins. What matters more is how we explain why some phases catch and keep on.

***

Safire begins his piece with the appeal pitched by Jackson, a black Presidential candidate, to white voters: “It’s a mutual growth process… what I call ‘raising the comfort level.’” It’s a minority figure’s call for the majority to shift their perception on what is “bearable” and “satisfactory,” if not “pleasant.” In 1990 (two years after Jackson’s run), the Times used “comfort level” in an article titled, “Harvard Law School Torn by Race Issue.” The title is deceptive as the piece is about a declaration by Derrick Bell, a black male professor, saying he would stay off the job until Harvard gave a black woman tenure. A black female student is quoted:

They have had years to find a black woman, but they just want to keep the status quo, what they call the comfort level of white men. The fact remains that we are getting only a white male corporate view of the law. We need black women mentors to tell us what it is like out there when we join a firm and start trying to get clients.

Same idea as Jackson’s situation, except add sexism on top of racism to the equation. You know from which side.

Ten years after Jackson’s hope of “raising the comfort level,” and a white woman uses the same euphemism to describe her reluctance in sending her daughter as one of the two white students in an all-black North Carolina charter school:

“I’m not going lie to you and say it does not test my comfort zone,” Mrs. Premont said. “But I knew enough about the school to overcome any comfort level issues that I had.”

My discomfort here isn’t caused by Premont’s judgment of the school’s tenor, it’s with using something like “comfort level” to describe it. Another piece around the same time uses phrases like “comfortably integrated to largely black” to describe a neighborhood that is actually striving for racial balance. I understand: sometimes the language grinds against the act.

The phrase of course isn’t isolated to issues of race. “Comfort level” often turns up when issues of gender inequality or scenes of sexual anxiety are being discussed, particularly in connection to businesses and institutions. In 1987, the Times used “comfort level” in articles about sexual politics in the office and one about merchandizing of fruit: “It has to do with the comfort level of the buyer. The buyer has to be comfortable knowing what the product is, who would buy it, what temperature it needs, does it require special handling.” OK. See? Comfort is relative. In the article on sexual politics, the men are uncomfortable because they feel threatened by women in the office. The women are uncomfortable because they feel diminished by men. Maybe, yes, ok? But when you have the luxury to maintain a rigorous comfort level about where your fruit comes from? That might better illuminate the present-day burgeoning of “I’m not comfortable with this.”

Like Jackson’s white voters, people who are able to dissect the origins and packaging processes of their fruit have a choice. The former might be race based, and the latter class based, but both have, in a word, privilege. They’re able to sense and articulate their discomfort because they have the option of remaining as they are, which is comfortable. The world is actually trying at all times to make their lives — those of the most comfortable — even more so. “Would men feel more comfortable shopping at drugstores?” asks a 1995 Times piece about the crises of emasculation men face whenever near cosmetics.

She attributes the male comfort level to the pharmaceutical look of the store and the packaging, the no-fragrance policy and the convenience of ordering by mail. She says one “older gentleman” in Italy orders 50 shaving creams at a time.

Who knows, it might be the most privileged — in terms of sex, race, and class — who feel threatened the most, who sense the greatest discomfort. Is it because they expect their comfort levels maintained at all times — that the world always to yield to them? Another article theorizes that only in America do supermarkets aim so desperately at making their clients feel at home:

to transport you into a place of chromatic familiarity, a ‘high comfort level,’ for the same reason that the music is slowed down: rather than try to rouse us from our coma, the soothing pastels and assuaging complexion seek to keep us in our drowsy 14-blink, 60-beat state. Slowly. More slowly. More time. More purchases. Slowly, now. Frozen spicy popcorn shrimp. Sleepy, now. More slowly.

The mood of this scene begins to sound something like a therapy session. Indeed, a company’s analysis of their clients’ comfort level begins to feel like a psychologist’s assessment of her patients. Get them at their most comfortable — their most vulnerable — and then get them on your team. The speech act “I’m not comfortable with that” could bring everything to a halt, so best to ease people in by putting them at ease. Comfort slides gradually, incrementally. Slowly. More slowly. More time. Sleepy, now.

Related: Histories of ‘Schadenfreude’ and ‘Blackmail’

Jane Hu is uncomfortable with the term ‘precarious.’