How To Make 17th-Century Delights: Whipp'd Syllabub

How To Make 17th-Century Delights: Whipp’d Syllabub

by Gina Patnaik and Lili Loofbourow

A series about recipes that may seem odd or outmoded and yet we’re curious to try!

Hospitality mavens of the 1690s knew that, if you were expecting company, you’d do well to serve up a nice cold syllabub. (As the nursery rhyme goes, the queen of clubs made syllabubs.) Syllabub, a foamy, marvelous vehicle for wine and cream and froth, inspired strong feelings. “I shall hate Sillabubs as long as I live,” announces Lady Addleplot, the “a highflown Stickler against Government” in Thomas d’Urfey’s play Love for Money. John Donne has a satire about two country bumpkins who choose a too-hot custard instead of “Choice Sillabubs with Sugar hill’d all o’re” to their mutual disadvantage. A pearl might be “as white as a syllabub,” and the proverbial swine before whom it was cast was, proverbially, “as shamefac’t as a sow that slaps up a syllabub.”

But George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, said it best: “Next — enter the sweet Sillabub of LOVE.”

To make a syllabub you’ll need cream, sack (the beverage — amontillado or sherry or white port or muscatel will work), two egg whites, and ¼ cup of sugar, plus flavoring spices. You will also need a syllabub pot — glass, ideally, with a spout through which your guest could suck out the syllabub from the bottom underneath. You may not have one. Never fear: we discuss some substitutions below. The enterprising cook will also need some birch twigs.

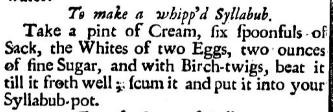

Here is your recipe, by one J.S., the 1696 edition of whose book, The accomplished ladies rich closet of rarities, is turning us into accomplished ladies.

To do a 17th-century recipe justice, you need 17th-century tools. You will need to fashion a whisking implement out of birch twigs.

Step 1. Find a birch tree. They look like this:

Make sure the bark looks like this:

Step 3. Abscond with some branches.

Step 4. Strip off a twig.

Step 5. Take off all the leaves. Wash.

Step 6. Tie the twigs together somehow, using rubber bands or ribbon — something hardy. Trim the twigs so they’re roughly the same size.

Step 7. Make sure you have all your ingredients: sugar, whipping cream, Moscato (or sherry, or white port), two eggs, and a whisk.

Step 8. Combine the ingredients: the whites of two eggs, ½ cup of wine, ¼ cup of sugar, and the pint of cream.

Step 9. Start whisking.

Step 10. Whisk for a long time. It will stay liquidy.

Whisk some more. Take turns with a friend. Perspire. Wonder if it is all for naught.

Try, experimentally, whisking a small portion in a different bowl with a modern-day whisk, to see if that makes a difference. It does:

Regret doubting the text; realize that the struggle of making your syllabub froth is part and parcel of making you into the accomplished ladies you will eventually, meringue-like, become.

Look up who invented the wire whisk. Marvel. Now that you’ve had a break, keep whisking with your birch twigs.

And at long last (though really it has only been fifteen minutes), you will have this:

Step 11. The recipe says to “scum it,” which implies there’s some liquid underneath from which to “scum” the froth. We overdid the whipping (Puritan zeal); it’s probably better to stop before it’s quite as stiff as the syllabub shown. If this happens to you, just say you’re using Sir Kenelm Digby’s book of recipes. Published four years after his death in 1669, it advises the syllabub-maker to beat the ingredients together with a whisk “till all appeareth converted into froth.” The next step would be to leave it overnight to separate out, such that “the next day the Curd will be thick and firm above, and the drink clear under it.” His recipe is worth reading in full, though — he was a man with ideas:

I conceive it may do well, to put into each glass (when you pour the liquor into it) a sprig of Rosemary a little bruised, or a little Lemon-peel, or some such thing to quicken the taste; or use Amber-sugar, or spirit of Cinnamon, or of Lignum-Cassiae; or Nutmegs, or Mace or Cloves, a very little

Step 12. Make the best of your overwhipped syllabub: since you don’t have a night for it to separate out, layer the froth over the amontillado or sherry or muscatel or white port. Decide it might be good with raspberries, so try putting it in layers.

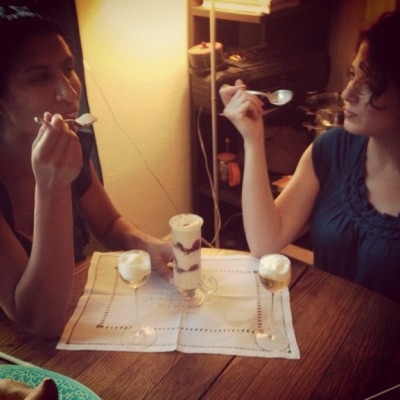

Step 13. Toast and taste.

Step 14. Evaluate. Lili thought it was good, Gina (who is a chef) thought it wasn’t, particularly. The syllabub is just okay layered over wine — it would definitely be better done properly. If we’d left the syllabub overnight to separate, the clear liquid that settled out would have been infused with the other flavors.

The raspberries with syllabub, on the other hand, were spectacular — the best combination of sweet, creamy, fruity and winy:

Verdict: if you don’t have time to let you syllabub steep overnight, serve it as an amazing cream with fruit for dessert.

Step 15. Serving. Improvise a syllabub pot.

A syllabub pot offers a way for each individual consumer to drink the syllabub from the bottom, without having to fight through the foam — here is a picture of one. (This is obviously how beer should be served too.) To achieve the same effect, you could just stick a straw in a glass or use a mate.

If the whipping seems like too much work, take heart. Syllabubs can be made without whipping (though we certainly couldn’t endorse it). Joseph Cooper, chief cook to Charles I, offered this recipe for a plain syllabub in his 1654 Art of Cookery:

Take a pinte of White-wine or Sack, and a sprig of Rosemary, a Nutmeg quartered, a Lemmon squeezed into it, with the peele, and Sugar; put them into the pot at night, and cover them till the next morne; then take a pinte of Cream, a pinte and halfe of new Milk; then take out the Lemon peel and Rosemary, and Nutmeg, and so squirt in your Milk into the pot.

Next up: what do with those two egg yolks left over from your syllabub-making.

Previously in Recipes For Disaster: Impossible Pie and Chemical Apple Pie

Gina Patnaik is a onetime chef and current Ph.D. candidate in English at UC-Berkeley. Lili Loofbourow is a writer in Oakland. She writes at Dear Television and over here

.