A Tale Of Two Tennis Shirts

by Jason Diamond

According to Google Maps, you have to walk 232.9 feet (17 seconds) to get from the Lacoste Boutique on Prince Street to the Fred Perry store on Wooster Street in Manhattan’s Soho neighborhood. Yet despite the fact that they’re practically neighbors, the stores feel like two different worlds. At Fred Perry, your salesperson is a short girl with a Scottish accent, a labret piercing, and a Chelsea Girl haircut. “Shot by Both Sides,” the biggest hit by Howard Devoto’s post-Buzzcocks band, Magazine, is blasting over the speakers, and the wares are arranged neatly, leaving sizeable gaps between each item in a way that leaves valuable floor space wide open. The shop looks modern, if by modern you mean ‘mod,’ which, as it happens, was one of the youth subcultures that incorporated the clothing brand into its uniform back in the 60s.

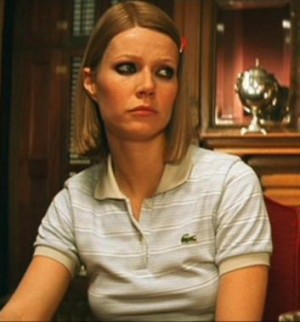

Across the street at the Lacoste store it’s an entirely different story: It’s bright, this season there is a ton of neon, and Rihanna is blasting out of the speakers. Shoppers are greeted by a gaggle of employees who, between them, fulfill just about every hipster cliché you can throw out — big glasses, asymmetrical haircuts, ripped up layers fashioned after Rodarte runway looks. The Lacoste shop is also very modern; modern as in, very much of the time and place it occupies.

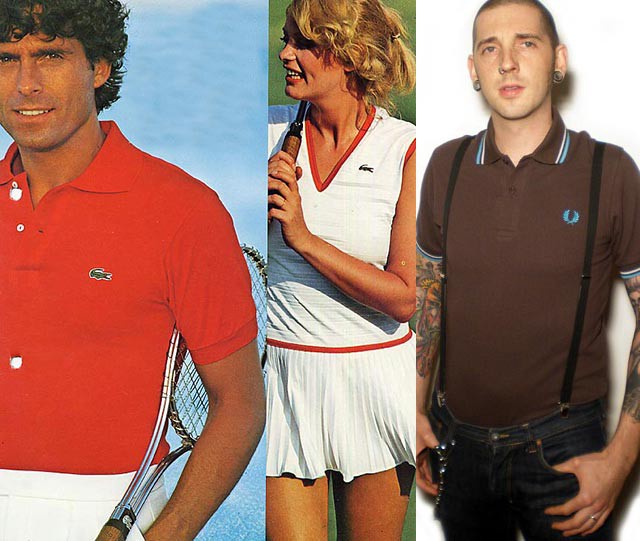

But what the two companies lack in comparable aesthetics, they make up for in their very similar histories: Wimbledon champions founded both brands — René Lacoste started his company in the late 1920s, while Perry’s shirts made their first appearance in 1952 — and both companies became famous for manufacturing very similar looking tennis shirts. These shirts are casually referred to today as “polo shirts” (which is technically wrong: the term polo shirt originally referred only to the long-sleeved button-up shirts worn by polo players). Even though the shirts look and feel similar and cost about the same (Lacoste shading a little less expensive), somewhere down the line the laurel wreath of Perry’s logo became a favorite of mods, skinheads, rude boys, football hooligans and Brit Poppers, while Lacoste became the sport shirt of choice for the rich and privileged and anyone looking to be seen as such. But why did it turn out that way?

***

I meet Paul for beers at a bar off St. Mark’s Place. Paul is about 6-foot-4 and built like a brick house. He’s got a muscular build that looks natural, not like it took years to chisel at the gym, “It’s working-class physique,” he says with a smile as he lifts up his right sleeve to show off the laurel wreath tattoo he got as a tribute to his favorite clothing brand.

With his buzz cut and imposing build, Paul looks like the stereotype of a Fred Perry loyalist, and indeed he’s worn the company’s shirts “at least three a week since the 1980s.” He grew up in England; he was fourteen when Margaret Thatcher became prime minister in 1979. He tells his story in a whimsical, almost Dickensian way: “I was a pissed-off kid. I’m not quite sure at what it was I was so angry with, but Thatcher didn’t help things much. So I decided I should let people know I was angry.” With the aid of his mother’s leg razor, Paul became a skinhead because “it looked fucking tough,” and, soon after that, acquired his first Fred Perry shirt through questionable means, “I took it off some guy’s back after a fight. I said to him, ‘that looks like my size,’ and I just pulled it off.”

As he reminisced about his reckless teenage years, Paul was careful to point out that, no matter how out of control the rest of his life got, he always took great care of his Fred Perry shirts because you “could only afford one or two of them.” Some of his friends, all skinheads, made fun of him, saying he looked like a “fucking mod” wearing Fred Perry shirts. “The real salt of the earth guys,” he said of them.

Paul outgrew the skinhead lifestyle around the time he says that it started becoming synonymous with the racist National Front. He’s the child of a white English father and a black, Jamaican-born mother, and his mother was alarmed by the images of angry men with shaved heads wearing Fred Perry shirts marching through the streets, chanting to deport non-English born citizens. “She didn’t understand I wasn’t one of those kind of skins; it was hard for her.” He continued: “I eventually got into E” — ecstasy — “and realized I didn’t need the violence. But I always wore Fred Perry. Still do.”

When I pressed him to explain why he thinks Fred Perry shirts became so popular among pissed-off British youth, his response was carefully chosen. “I’ve always been a Man. United supporter. All my friends were Arsenal, but my dad was from right around Manchester.” He paused. “They weren’t the team they are now, but I suppose if Bestie [late soccer legend George Best] had made shirts, I’d be wearing them today instead.” When asked whether he’d ever consider buying another brand of tennis shirt, he doesn’t hesitate for a second: “No.”

There are a lot of brand loyalists like Paul, and the continued popularity of Fred Perry shirts among the likes of contemporary skinheads to “The Modfather” Paul Weller, and the Pitchfork-approved Danish hardcore band Iceage as an idiosyncratic factoid that Malcolm Gladwell could write a New Yorker article about. It’s easy to attribute the phenomenon to tradition, like loud music and drugs, and figure that the shirts are just part of the entire youth culture package. But why Fred Perry? Why not Lacoste? The two shirts are practically identical: Both 100% cotton pique tennis shirts, both retailing in America for $85 to $90. Yet somewhere along the way, Fred Perry shirts became linked to a skinhead culture that prides itself on its working-class background, while Lacoste shirts, called the “sport shirt of choice” by The Official Preppy Handbook in 1980, have been a country club staple ever since. Two shirts named after athletes who excelled in a sport that is generally played and enjoyed by people with the leisure and money for expensive lessons and court time.

But while Lacoste and Fred Perry may have built the same shirt, Lacoste was built from the top down and Fred Perry from the ground up.

***

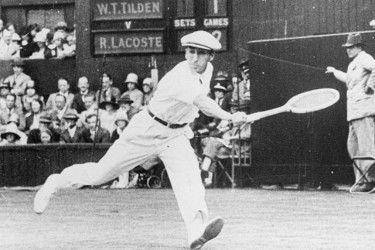

To begin, understand that René Lacoste is the father of the modern tennis shirt. Before Lacoste, tennis players were running up and down the court wearing uncomfortable flannel trousers and shirts — style won over functionality in those days. Trying to keep the players looking clean and proper, Wimbledon officials instituted a strict “tennis whites” rule in 1890, the light colors better camouflaging the players’ sweat. Lacoste, the son of a wealthy businessman, was one of the world’s best tennis players. Enrolled into one of the most prestigious schools in France, Lacoste was pegged to follow in the footsteps of his businessman father. Instead, he found himself attracted to the game of tennis. His father (an understanding man, to say the least) gave his son five years to excel in the sport. By 1925, he’d won his country’s major, The French Open, becoming one of the “Four Musketeers” of French tennis, a group that won a combined 20 Grand Slam titles for their country between 1924 and 1932.

Even during the height of his playing career, Lacoste’s creative streak never left him. He’s credited with creating the world’s first tennis-ball machine, and, long after his 1963 retirement, he took out a patent on the tubular steel tennis racquet. But it’s his short sleeve jersey petit piqué cotton tennis shirt that was his most revolutionary creation. Sleek, stylish, white, and, above all other things, comfortable, Lacoste first wore the shirt during the 1926 US Open (which he ended up winning), and the new style became a sensation.

Lacoste was the first athlete to sell merchandize emblazoned with his logo: the now ubiquitous crocodile (In fact, the Lacoste company claims, to some dispute, that Lacoste’s shirt was the first article of clothing to sport a visible brand name.) In 1933 Lacoste co-founded La Société Chemise Lacoste, and the shirts went on sale to the public.

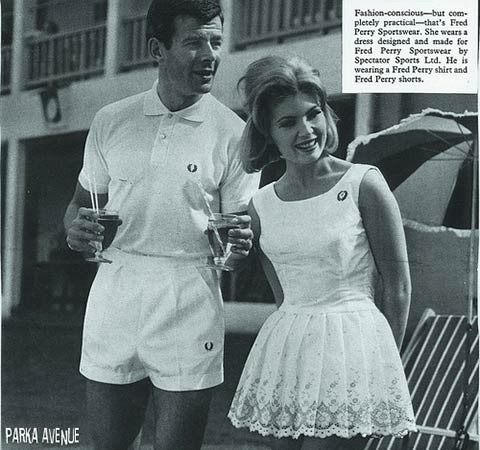

Fred Perry, who was five years younger than Lacoste, spent much of the 1930s as one of the best players in the world. He won three Wimbledon titles and was the first player to win all four Grand Slams in his career. Seeing Lacoste’s success, Fred Perry launched his own tennis shirt line in 1952 during his native country’s biggest tennis championship, Wimbledon. The shirts became a huge success in England, outselling Lacoste shirts within five years, and the company eventually moved into other tennis gear. As Paul described it to me, “It got to be like Michael Jordan and Nike. They were comfortable and your dad wore them on the weekends even if he didn’t play [tennis].”

While Fred Perry focused on growing its business in England, Lacoste was expanding westward. The shirts first appeared in the U.S. in the early 50s, at the then-hefty price of about eight dollars apiece. Marketed as “the status symbol of the competent sportsman,” the shirts were sold in high-end department stores on Madison Ave. and by Brooks Brothers. They were a hit. After taking over the company from his father in 1963, Bernard Lacoste — along with the British clothing company Izod, who purchased a stake in Lacoste in 1953 — the company started outfitting presidents and entertainers. By the mid 60s, the company had expanded to offer shirts in a variety of different colors.

Meanwhile, Fred Perry shirts remained a very English garment. They were passed down in working-class families from fathers to sons, looking fashionable enough to be matched with army surplus parkas leftover from the war, pork pie hats, and sta-prest trousers as part of the uniform for mods of lesser means that couldn’t necessarily afford the expensive custom suits that other mods wore.

Soon, the “hard mods” were choosing more working-class accessories like work boots and suspenders, and the skinhead subculture evolved out of that fading London mod scene. By the close of the 60s, The Who were putting out rock operas; amphetamines gave way to psychedelics; and in many cases, mods became hippies. While the association between skinheads and racism is now almost instant — thanks to organizations like the National Front latching on to their tough look — they were the working-class face of British youth subculture before punk, and Fred Perry tennis shirts were an important part of the equation.

The 1980s turned out to be the decade of the tennis shirt; closets all across America held Penguins and Le Tigres. Lacoste and Ralph Lauren battled for the hearts and cash of Americans from coast to coast. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s possible to see that Lauren’s Polo brand won the battle, due to Lacoste’s oversaturation of the market and Lauren’s superior branding. In a 2006 interview with Businessweek, René Lacoste’s grandson, Philippe Lacoste, discussed the company’s fall from grace, saying its prestige “eroded over time because we expanded our distribution channels, and even were sold in J.C. Penney.”

By the time the 90s rolled around, the preppy look was out and nobody was calling tennis shirts by their proper name anymore. They were now “polo shirts.” Advantage: Ralph Lauren.

Fred Perry didn’t make it much out of England until the late 1990s. In the U.S., it was seen mostly as a straight tennis brand. But eventually, as time went on, buyers at big-name department stores like Neiman Marcus and Nordstrom realized that the label was big among popular Brit Pop musicians like Oasis and Blur and added Fred Perry to their merchandise. The brand became progressively less tennis associated. In 2010, they produced a line in collaboration with Amy Winehouse, and the rebranded Fred Perry got into live music by sponsoring the Dot to Dot music festival that featured (among others) indie bands like The Drums.

Lacoste still has a hand in the tennis world. The brand dresses the American star Andy Roddick along with almost a dozen other pro players. Perry had a deal with Andy Murray — the player that many believe has the best chance to be the first player from Great Britain to capture a Grand Slam title since Fred Perry himself beat American Don Budge at the 1936 US Open — until Murray signed a more lucrative deal with Adidas in 2009. The company still has a tennis collection, but it’s made up of four pieces of clothing: white shirt, white shorts, a white tennis sweater and a white tennis jacket.

But the shirts created by René Lacoste and Fred Perry stopped being about tennis a long time ago. From an advertising standpoint, tennis is the sport most associated with luxury. If you want proof, just open a magazine and find the ad featuring one of the games greatest players, Roger Federer, trying to sell Rolex watches; or look at the companies who sponsor the Grand Slam events: Mercedes, J.P. Morgan, Evian, and Grey Goose. The tale of the two tennis shirts is really a case of commodity fetishism: Lacoste is a luxury brand, so people with money wear Lacoste, and the people who run Lacoste market to their base. Fred Perry clothes are also expensive. Fred Perry has shops in high end/high price shopping areas all over the world and a dedicated following. People associate Fred Perry with rebellion and youthfulness, and that relationship is why the company has thrived for so long without expanding and marketing as aggressively as Lacoste. But at the end of the day it’s the same thing as Coke or Pepsi, Ford or Chevy, Apple or Microsoft: You’re either a Lacoste person or you’re a Fred Perry person. But either way, you’re just wearing a tennis shirt.

Jason Diamond lives in New York. He also lives on Twitter.