"You Get On The Internet And Pretty Soon You're Drunk": The Orthodox At Citi Field

“You Get On The Internet And Pretty Soon You’re Drunk”: The Orthodox At Citi Field

by Sean Patrick Cooper

While the ultra-Orthodox steadily streamed down the 7 train platform and onto the pavilion, a group of four teenagers sat around the big red New York Mets apple, waiting for their friends. This was last night, an hour or so before the Citi Field gates opened. Outside the stadium, a few hundred ultra-Orthodox Jewish men stood around, waiting for the masses to arrive to this rally about the dangers of the internet. The 40,000-stadium tickets had sold out the week before and the event organizers — The Union of Communities for the Purity of the Camp — had scrambled to rent nearby Arthur Ashe Stadium for the 10,000 or more attendee spillover. These boys were among the other early arrivals. One of them, tall and skinny, with his wide hat tilted up over his face, came over to speak to me, his words coming out in excited staccato bursts.

“You get on the internet and pretty soon you’re drunk,” he said, as he mimicked a person wobbling back and forth. “You’re drunk on distractions, and you can’t get back to focusing on your studies or to your work or to your family.”

One of the boys took a call on his cellphone from a friend who’d just arrived by bus. The group left to go find him in the parking lot.

“Well, now I don’t know what I’m going to do,” said the boy who stayed behind. “I guess I’ll just wait here for some action.” He wore a thick black coat and rimless glasses. Columns of curls framed his round face on either side like fly traps. He was 16, in his third year of what I would consider high school.

We chatted for a bit, and he explained to me how the internet affects his mind. “I had an iPod touch for a while and it was really bad. I’d go find a bench outside an apartment complex and get on someone’s wi-fi signal, and watch Youtube videos of car chases, cop chases, action movie scenes. Watch them for hours. Then I’d get some video games on there and go home and play them till 3:00 in the morning and be wrecked when I woke up. Just ruined the whole day, my mind all scattered. I couldn’t stop,” he said. “You know, it’s sort of like smoking cigarettes, and when someone asks you, ‘When are you going to quit?’ ‘Well, I’m going to quit when I have this last one.’ But there’s always one more after that last one, and another pack after that. You can’t really quit once you start because you’ll always have one more last one.”

He had bought his iPod Touch from Walmart and recently sold it to a classmate, but still goes with friends who have iPods to sit outside apartment buildings to watch clips on Youtube. Behind us, a barefooted man wearing a leopard-printed toga started jumping up and down. He raised a Fred Flintstone-style club at the passing crowds, and yelled something incomprehensible about not using electricity or cars. He was with a satirical protest group called Cavemen.

“I wish someone would put him back in his dog cage,” the teenage boy said, smiling. “I’m worried he might come over here and bite me.”

A few minutes later, a group of Orthodox men gathered around a pair of women protestors talking loudly with an older man with a neatly trimmed grey beard. Around them stood media people taking their picture. “Yes, but you don’t seem to understand the thrust of the protest,” the man said.

If the young woman was genuinely confused about the rally’s intent, so too were many of those in attendance. It was widely known the rally was to be about the dangers of the internet, and it was speculated that its speakers would use the rally to define what role the internet should play in the daily lives of the ultra-Orthodox community. But in the weeks leading up to the event, the message from the organizers was mixed. Some were saying that no proper Jewish home should have internet access, and probably not even a computer. Other interviews and statements implied that the internet was okay to use, but only if it were filtered with special software and being used for business.

In a letter to the parents of students enrolled in a Prospect Park Yeshiva, administrators wrote that “they demand that each and every parent attend this special gathering.” Similar letters from other schools floated around the internet in the days leading up to the event. For the women who weren’t allowed to attend — it has been decided shortly after the event was announced that it would be a male-only rally, it being deemed too complicated to divide the stadium into separate gender sections — live video streams were being broadcast to gatherings in Dallas, Chicago, and Detroit, Los Angeles, Cleveland, and Miami, Toronto, Mexico City and as far away as Brazil.

As afternoon closed in, the sky was blue and the sun was warm and there was little humidity in the air. Families, wandering over from Arthur Ashe Park with children in strollers, looked around in confusion and then headed back over the boardwalk bridge. Hundreds of buses were on their way to Citi Field, coming in from the ultra-Orthodox communities of Flatbush, Williamsburg, and Monsey; from Lakewood, New Square, and Kiryas Joel.

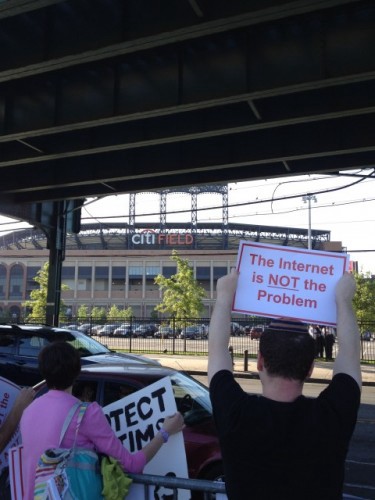

Down the street from the subway platform, the small group of Caveman protestors gathered about fifty feet away from a larger and better organized protest group called The Internet Is Not A Problem. The large group, maybe a hundred strong, was led by Ari Mandel, who had the idea to organize the group after speaking with his friend, Chanie Friedman, both of whom were frustrated at what they saw as a misdirected use of energy by ultra-Orthodox leadership. The greatest threat to the community wasn’t technological, Mandel told me, but rather how the community was addressing cases of sexual abuse of children. He pointed to a pair of recent New York Times articles that exposed a potentially massive problem within the tight-knit Jewish community, wherein victims and their families were being discouraged from, and sometimes even ostracized for, speaking to the police about instances of sexual and physical abuse against their children.

As cars and buses passed by into the parking lot, Mandel and his group held signs with messages like “The Internet Never Molested Me” and shouted sing-song slogans.

“There’s some back and forth here between us and the people in the cars, but there’s no serious dialogue yet,” said Mandel. “Just a few people who’ve come up to us and told us we’re embarrassing ourselves and the community.”

Friedman stood beside Mandel, holding a small sign as she leaned against the metal barricade separating the protestors from the crawling traffic. “They don’t want to understand the consequences of child sexual abuse, of what happens when you’re exposed to that,” she said. “I read on a Yiddish forum someone saying that the whole concept of sexual abuse is made up by the Goyim, the outside world.”

She continued: “There’s this attitude within the community that this is just something that happens. They’ll say, ‘It happened to my father, and to his father, and it’s just no big deal.’ But the focus on the internet is just a distraction from what’s really going on here.”

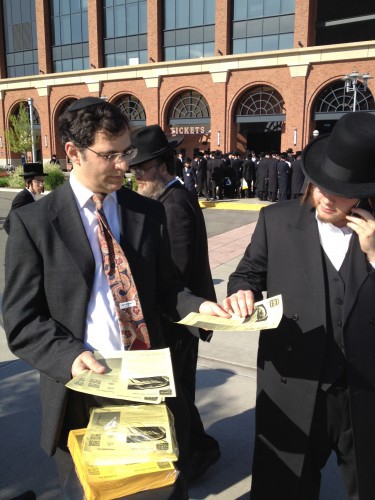

The police presence at the event was heavy but mostly confined to the background. Bomb-sniffing dogs were kept on short leashes around the perimeter of the parking lots. Getting closer to the stadium, you could feel the mood lighten to an almost jovial atmosphere. Some of the men were taking pictures together, posed underneath the glowing neon of the Citi Field signs. Near the left field gate, a man wearing a dark grey suit and a floral print tie handed out yellow flyers for his new product: An iPhone app designed to locate kosher delis and restaurants.

“I mean, it’s not practical. You can’t ignore the internet,” he said, as men in suits darker than his grabbed his flyers. To the passing event goers he said, “Free app here, not the internet. Find kosher minyanim and mikvahs.”

“I’m here to get the word out about this,” he told me. “I mean, look around, we’ve got, you know, 40,000 potential users here. Right now, we’re looking at 25,000 active app users. And I’m working on trying to find some advertisers. I need big advertisers who will pay a flat rate instead of this five cents an impression deal.”

A man in a black fur hat asked him what, exactly, was an app, and he explained it to him. The man grimaced and walked away.

By 7 p.m., the stadium was awash in an ocean of black suits with specs of white poly-cotton. It was an awesome sight, and bizarre, too, to see the empty baseball field surrounded by a capacity crowd of religion traditionalists. For whatever reason, the organizers decided to arrange the event speakers and esteemed guests on a purple dais behind the center field wall, instead of on the infield. High-ranking ultra-Orthodox clergymen took to the podium while above them a video feed zoomed in on their bearded faces. The speakers, ranging in age from forty to perhaps seventy and older, were a rhetorically gifted group. A few were even eloquent. A couple spoke only in Yiddish, but the rest delivered their speeches in strong English, peppered with Yiddish phrases. Inconsistent subtitles appeared sometimes in real time, and sometimes obviously delayed and incoherent, on the huge screen behind them. The phrasing varied from speech to speech, but the message, roughly speaking, was the same throughout: Modern technology poses pitfalls for a servant of God. There are serious questions about who needs the internet and who does not, since the internet does not belong in a Jewish home, even with a filter.

Social media, speakers argued, is a technological evil that is destroying the community’s sensibilities, sensitivities “and the way we think and live.” Many of the speakers made this point as well: Our way of life might appear to be intact on the outside, but on the inside, there are problems.

For hours the speeches went on, sometimes too loudly as they boomed over the PA system and echoed around the empty, manicured infield. In a general way, the ironies and contradictions of the event seemed almost too obvious to point out: the organizer’s use of modern technology to transmit each speaker’s critiques of modern technology to audiences around the world. The fact that in nearly every row of seats, there were men checking the screens of their Blackberries or iPhones. Less obvious but still lingering in the air was the uncertainty that the internet was really the corrosive evil the organizers made it out to be. Didn’t many men in the stadium make their living online? Wasn’t the event bankrolled, in part, by the owner of B&H; Photo, an electronic store with a strong online presence? Towards the end of the rally, many of the men in the crowd had the glazed gaze of the bored and obedient. Others were walking towards the door.

Near the end of the rally, a man in a dark black suit and tall hat asked me to take a photograph of him looking through a glass entrance door. “One with me holding the binoculars and one without,” he said, while he posed carefully against the glass. I snapped both photos while he looked on intently at a TV screen broadcasting the rally.

“Why do you want the photos of yourself?” I asked.

“I need proof that I was here, or else I’ll get in trouble. I got two pieces. This parking ticket stub,” which he pulled out of his pocket, as if to prove to me he was actually standing right there. “And now the photograph of me outside the building. It’s so people will believe that I came, so they know I was really here. Sometimes you gotta go the extra step to prove to people where you are.”

Sean Patrick Cooper’s writing has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail, The Millions, The Rumpus, and other places too. He’s currently studying literary reportage at NYU, and at work on many pieces that are almost done.