The Cup Of Coffee Club: The Ballplayers Who Got Only One Game

The Cup Of Coffee Club: The Ballplayers Who Got Only One Game

Of the 17,808 players (and counting) who’ve run up the dugout steps and onto a Major League field, only 974 have had one-game careers. In baseball parlance, these single-gamers are known as “Cup of Coffee” players. The number fluctuates slightly throughout each season as new prospects get called up to fill in for injured veterans, or when roster size expands in September. (Last year, for example, Braves rookie Julio Teheran was a Cup of Coffee player for the eleven days between his MLB debut and a spot start.) But staying on the list for an extended period of time is generally not a good sign. It’s an ominous one, an indication that something’s gone horribly wrong, that however long a person has worked to attain his dreams, all he was allowed was a brief glimpse before the curtain was yanked shut in front of him. The Cup of Coffee club is filled exclusively with people who do not want to be members.

***

Ed Cermak, all of 19 years old, trotted in from right field to take his first hacks at Major League pitching. Three quick strikes later and he was back in the dugout, most likely shaking his head at the dramatically better pitching he was now facing. His next three at-bats all met the same end: Strikeout, shaken head, strikeout, shaken head, strikeout, shaken head. The dreaded Golden Sombrero, although they didn’t have a cute phrase for something so disheartening back then. In 1901, they probably just called it A Day To Forget. He never would, though, seeing as it would be the only Major League memory he’d have.

***

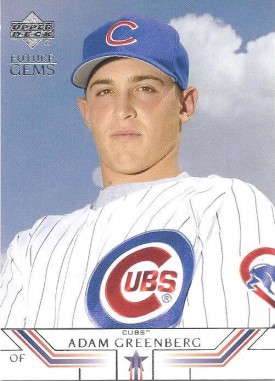

“My job was to get on base,” Adam Greenberg has been quoted as saying many times. “I certainly was successful in doing that.” The quote is pure reporter-bait, honed to perfection after a half-decade discussing and revisiting a single pitch, and now he repeats it to me on the phone, no doubt sick of it as this point.

On July 9th, 2005, Cubs skipper Dusty Baker told Greenberg to grab a helmet and pinch-hit. He’d been on the squad less than 48 hours, just called up from the Double-A team in west Tennessee. Walking up to the plate gave him a few butterflies in the stomach, but they had disappeared by the time he reached the box. It was business time. He set his feet, made mental notation of where the outfielders were positioned (“Juan Pierre was shaded to the left”), eyed Marlins reliever Valerio de los Santos and got ready to attack the first pitch he saw; lessons in the minors taught him that the first one might be the best one he was going to see.

A 92-mph pitch takes 400 milliseconds to traverse the 60-foot-6-inch distance from the pitcher’s mound to home plate. That’s the high end of how long it takes for a human eye to blink. Instincts take over when dealing with these kinds of speeds, skills that have been honed over years of repetition. Sensing that something was off about the ball’s trajectory, the auto-response of Greenberg’s body was to turn away from the incoming projectile, protecting the exposed vital sense-collecting organs on his face at all costs. As an offering, his body was willing to sacrifice the back of his head.

“The first thing going through your head is, this guy’s dead,” said de los Santos in a 2007 “Outside the Lines” segment about the pitch. Greenberg suffered a mild concussion, which led to years of vertigo and headaches. The following season, he hit .179 and .118, respectively, in Double-A and Triple-A, forcing the Cubs to cut ties with him. Subsequent minor league tries with the Dodgers, Royals and Angels all met the same end.

Last year, the 30-year-old Greenberg set out to get out of the Cup of Coffee club once and for all. Trying to reclaim the skill set that once allowed him to play the sport at its highest level, he took hacks with the Bridgeport Bluefish, an independent team in Connecticut full of former top prospects and those no longer worth the farm club roster space. “It’s a whole bunch of guys with similar stories,” Greenberg told me. “And we’re all in this league, trying to get out.”

Another guy “trying to get out”? A former Marlin now Long Island Duck by the name of Valerio de los Santos.

In late April of last year, Greenberg and de los Santos faced each other for the first time since that fateful pitch in 2005. First pitch: fastball inside. “He threw me a hard cutter that started right in at me and fell over the plate,” Greenberg told ESPN Page 2 after the game. “At that point, it was like he’s good, I’m good, so let’s play.” Three pitches later and another de los Santos-Greenberg match-up led to the batter getting to first base, this time the result of a single. “The greatest single of my career.”

For the season, Greenberg finished with a modest .259 batting average, good for 12th on his team. But his on-base percentage, a stat that counts way more substantially seeing as there’s nothing more important than getting on base, finished at .393, the best on his squad. While much of this discrepancy is due to Greenberg’s ability to draw a walk, it should be noted that he also led his team, by a wide margin, in the amount of times he got to first base after being hit by a pitch.

But that was last year. He never got called back up, and this year he’s no longer with Bridgeport. According to his Twitter, Greenberg’s now spending his time hawking a dietary supplement that, according to its website does, well, everything. But despite his new gig, Greenberg’s profile still lists him, right there in the number one spot, as a “Professional Baseball Player.”

***

On the final day of the 1963 regular season, John Paciorek had a hell of a career. The 18-year-old started in right field for the Houston Colt .45s — two years away from trading in the handgun for the Space Race-influenced “Astros” moniker — and had a perfect day at the plate: three-for-three, two walks, three RBIs and four runs. Nagging back injuries meant he’d never have a chance to blemish that perfection.

***

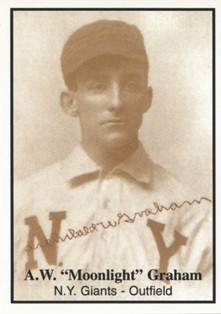

The most famous Cup of Coffee player of all time, due exclusively to his appearance in W.P. Kinsella’s 1982 novel Shoeless Joe and its subsequent film adaptation Field of Dreams, has to be Archibald “Moonlight” Graham. His story is now well known: He entered a 1905 game for the New York Giants as a defensive replacement in the eighth inning. Three outs later, he trotted in from right field and picked up a bat. He was due up fourth, meaning the team would just have to muster up one base-runner for him to see a Major League pitch. But, alas, his teammates failed him and he was left in the on-deck circle when the umpire called the final out. He never got to take a single hack at the ball.

Like Graham, fellow Cup of Coffee player Ralph Gagliano never got a chance to swing a bat either. But unlike “Moonlight,” he didn’t get a chance to wear a mitt either.

“Digging up old bones, eh?” he said, when I reached him after a short game of phone tag.

During his time as a Major Leaguer, the only part of the field that Gagliano’s spikes treaded upon was the 90 feet of dirt between first and second base in the Bronx, where old Yankee Stadium used to reside. “I could’ve had the shortest career in history,” Gagliano told me with a laugh.

Drafted by the Indians in 1964, Gagliano was a “bonus baby,” a top prospect to whom the team signed to a Major League contract in order to keep other teams from stealing him away. “A number-one pick these days,” he said with pride. Gagliano tore knee ligaments during his first spring training, sending him to the DL until he was finally activated and placed on the big league roster on the first day of September. The shy 18-year-old kept a low profile for his first few weeks in the majors, never even speaking to manager Birdie Tebbetts. “He probably thought I was just some guy hanging around the locker room.” But Tebbetts must have just been playing dumb. In the 9th inning of a 9–4 game, he decided to give shortstop Larry Brown a break and called out Gagliano’s name to punch run.

“Joe Pepitone was playing first base,” Gagliano recounted. “He asked about my brother Phil, who played against him in the minors. I don’t even know what I said, I was so scared. I took about a two-foot lead.” He laughed at the memory his old fearful self. After “two or three pitches,” the next batter grounded Gagliano into a force-out at second, leaving him with a fleeting trophy of his MLB career. “I had to slide so I ended up getting a nice strawberry,” he said. “So I had a little wound on my butt, made me feel good.”

Gagliano’s next two-and-a-half years were spent in the military during the Vietnam buildup. By the time he was ready to return, the game had passed him by. “My number didn’t get called again,” he said. His voice held no regret — it was a long time ago. “That’s just the way it goes sometimes.”

***

It just wasn’t Ron Wright’s day. His first career at-bat ended how many first career at-bats end: three straight strikes, back to the bench. But his second was truly something to behold. With runners on first and third, nobody out, he hit into the unique 1–6–2–5–1–4 triple-play, that last 1–4 connection coming when pitcher Kenny Rogers threw to second baseman Michael Young, tagging out the gambling Wright who was hoping to swipe a base while teammate Ruben Sierra was stuck in a third-to-home pickle. But Wright knew his third at-bat would be his redemption. He was feeling more comfortable, loosened up. He knew he’d get a good pitch to hit with Rogers’ first offering, so he took a hack and hit it on the screws. The man who’s earned more money playing the sport of baseball than anyone else in the history of mankind happened to be in the right place. Alex Rodriguez started the 6–4–3 double play. Wright’s three at-bats resulted in six outs. He wouldn’t get the chance to do any more damage.

***

Baseball is a game of connections. The sport’s unique combination of team battles (Dodgers vs. Giants) and individual skirmishes (Tim Lincecum vs. Matt Kemp) lends it to a “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon”-esque existence. So-and-so pitched against such-and-such who was on whoever-the-hell’s team. Each game creates a new filament that bonds different pieces of information. Former pitcher Rex Hudson is one of those bonded links.

“The first batter I faced was Hank Aaron,” Hudson said. He spoke to me from his home in the philosophically-named Texas town of Ponder (Population: 507), where he retired to after 25 years working at the Albuquerque regional air traffic facility. “And I got him out.”

The first two innings went according to plan, the only mark on the scorecard being a double by Dusty Baker, another link that bonds in this essay alone. But his inexperience showed up in the third. “I didn’t know how to warm up properly. I must have thrown about four innings’ worth of pitches in the bullpen,” he says, laughing at his rookie mistake. On the mound, fatigue set in. A single begat a double begat a single begat a home run begat another home run. “I could’ve rolled it up there and they would’ve hit it.” Three runs, no outs, back to the showers. But it was the first of those two consecutive home runs that earns Hudson a permanent place in the annals of baseball history.

“[Catcher] Joe Ferguson came out to the mound with two on, nobody out and said ‘Let’s pitch him inside. So I threw it inside and he deposited it in the bullpen. Johnny Oates picked up the ball from the bullpen, wrote ‘726’ on it, and put it in his pocket.”

It was a singular souvenir: the ball that broke the old home run record. Until, that is, Hank Aaron hit two more ten days later off Padres pitcher Bill Greif, weaving another delicate strand in the game’s spider web.

***

Manager Hughie Jennings was in a bind. The night before, his star Ty Cobb had responded to a fan’s heckle of “half-nigger” by entering the stands and beating him senseless. When onlookers pointed out that the guy being pummeled was missing one hand and three fingers from the other, the player reportedly said, “I don’t care if he got no feet.” AL president Ban Johnson responded to the incident by suspending Cobb, indefinitely. The rest of his Tigers team, knowing they had no shot without him, refused to play until Cobb was reinstated. So here was Jennings, walking the streets of Detroit, trying to patch together a rag-tag team of scrubs to avoid a $5,000-a-game no-show fine from the league. And there, standing on a random street corner, stood 20-year-old Allan Travers. He’d never pitched a game in his life, but he was up for the challenge. That night he’d throw eight innings in front of 20,000 fans and give up 24 runs on 26 hits, closing out his career with a 15.75 ERA. But it most likely wasn’t the bombardment he remembered years later. It was the one batter he managed to strike out.

***

“You know those donuts on the bat?” asked Bill Schlesinger, 69 years old, speaking with the slow confidence of a seasoned storyteller, knowing the payoffs come without having to rush.

Everyone who’s ever played little league knows what Schlesinger’s talking about: They’re the weighted rings players put on a bat to add a bit more heft to their practice swings, the purpose being that, theoretically, when they get up to the plate to take real hacks, the bat will feel lighter. While the science behind using such an apparatus is sketchy at best, it’s one of those unquestioned rituals that start young and filter their way into professional ball: Add a donut, take a few swings, you’re good to go. Of course, there is a final step to the process that may be the most vital.

“I was on my way to home, tapping the bat on the ground to get it off… and it wouldn’t come.” While his voice didn’t change, a slight shift in his inflection indicated a smile was forming on his face. “The umpire had to help me, so everyone’s laughing and making fun of me.” He paused to let the story linger there.

Schlesinger’s only at-bat was a comedy of errors. On the Boston Red Sox from day one of the 1965 season, the 18-year-old had become accustomed to spending the long hours between first pitch and final out talking shop with equipment manager, Don Fitzpatrick. “I’d just take batting practice and sit in the corner,” he said. When manager Billy Herman finally made the call, Schlesinger wasn’t the only one shocked. “Fitzie says, ‘Oh my god, he wants to you pinch hit,’ so he ran back to the clubhouse and got my bats. I didn’t even have my bats there.”

The rest of his at-bat saw him getting grief from the umpire (“I got a dinner engagement in about an hour, no sense in you looking down to third for signs, kid”) and learning the manifold deceptions of catchers (“We’ll just give you some fastballs to get this over with,” which they obviously didn’t). It ended with a little tapper back to the pitcher. “And that was that.” Three days later, the Red Sox tried to send him to the minors, but he was snatched up by the Kansas City Athletics on a waiver claim, who in turn stuck him in their own farm system. But that was actually just the beginning for Schlesinger.

The next five years were spent working his way back up through the farm clubs of various major league teams: Single-A Winston-Salem to Double-A Mobile to Double-A Pittsfield to Double-A San Antonio to Triple-A Tacoma to Triple-A Eugene; Oakland to Boston to Chicago to Philadelphia. He was hitting .254 with 18 home runs and 13 stolen bases — the power/speed combo everyone was waiting to develop — when Eugene manager Frank Lucchesi called him into his office. Lucchesi was given notice that he would have the big league managerial job next year — he’d be sending signs from the dugout of the Philadelphia Phillies — and his first order of business was taking his best Triple-A players with him. “He thought I was ready for the majors,” said Schlesinger. But dreams of a second Major League at-bat lasted about two weeks, when an errant pitch came up and inside. “Got hit in the cheekbone, part of the earflap,” he told me matter-of-factly. As with Gagliano, any heartache he may have felt has been callused over by time. “Lost 40 percent of my vision and still can’t see today.”

As his former Triple-A teammates — Larry Bowa and Denny Doyle, among others — were taking their swings in the majors, Schlesinger had to relearn how to even see a ball. When he came back the following season, he hit .190 before the Phillies decided to send him to the bench and have him work off the rest of his contract by scouting high school games for up-and-coming talent. He was given his release from the team in the winter of 1970.

After a year out of baseball working at his dad’s hardware store, Schlesinger sent off letters to every team in the league, begging for one last shot. The Pirates eventually gave him one. But in his first game back, another up-and-inside pitch hit him in the head. This time, luckily, it just grazed the bill of his helmet, but it indicated a bigger issue. Said Schlesinger, “I didn’t see it.” Joe Brown, owner of the Pirates, noted the lack of reaction from his perch in the stands, jumped over the small fence near the dugout and took Schlesinger out of the game himself. After a ten-minute long chat in the clubhouse, Brown told him that that was it. It’s not worth it. “Go back to Cincinnati and help your dad with the store.”

His career was over, but he still had his stories, including his brushes with one of the Hall of Famers who occasionally showed up to spring training.

“So I get out of the batting cage and Ted Williams says to me, ‘You know who I am?’ and I say, ‘Yeah, you’re Ted Williams.’ ‘Let me ask you something, kid. Do you think I was a good hitter?’ and I said ‘Oh, you were a real good hitter, Mr. Williams.’ That was a mistake. I said ‘real good.’ ‘Real good? Real good? Let me tell you something, kid. I was the best goddamn hitter that ever lived and don’t you forget it. I was the best hitter in the past, present, and in the future. That’s the way it’s going to be and that’s the way it’s always going to be.’ ‘Yes, sir.’ ‘Now go in the outfield and I’ll hit you some balls.’”

Schlesinger took a moment to choose which tale he’s going to tell next. “But boy, I got some stories about him…”

***

Three-foot-7-inch Eddie Gaedel got an at-bat for the St. Louis Browns in 1951. Gaedel had been secretly signed to the team the night before, one of the publicity stunts of showman owner Bill Veeck, who called him “the best darn midget who ever played big league ball.” When pitcher Bob Cain couldn’t find the one-and-a-half inch strike zone, Gaedel trotted to first base to a standing ovation before being removed for a pinch runner. Seeing as it was his only at-bat, Gaedel is tied for the Major League record for highest on-base percentage. Forty-seven other Cup of Coffee players share the mark with him.

***

“Can you hear the hail on the phone?” Jeff Banister asked. He was in his car, 160 miles from his destination of Charlotte, waiting on the side of the road for a treacherous downpour to abate.

Both times I’d called previously, the phone had gone directly to a voice service that played a snippet of Toby Keith’s “Love Me If You Can,” the defiant song Keith recorded after laying down the tracks for the pro-war “Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue.” “You may not like where I’m going,” Keith sang to me over the phone, “but you sure know where I stand.”

Working as field coordinator for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Banister’s job is, to paraphrase Keith, to make sure everyone knows where the team stands. He oversees the entirety of the development process, including instilling a game philosophy that starts in the minors. “I like to say I’m managing the men as well as the boys,” says Banister.

His lone at-bat — a legged-out infield single — is less noteworthy than everything that surrounds it.

In high school, he was diagnosed with cancer in his ankle bone. Doctors considered amputation, but seven operations allowed him to keep the foot and, eventually, got rid of the cancer. In college, while playing catcher, he was run over during a play at the plate, resulting in three shattered vertebrae. He overcame these setbacks and was drafted in the 25th round of the 1986 draft. After toiling in the minors for seven seasons, accumulating over 1,600 plate appearances in the process, when he finally got the call to the majors, he couldn’t believe it was actually happening.

“[Roommate] Jeff Richardson and I used to always joke whenever the phone would ring late night, and say, ‘Hey, we just got called up,’” said Banister. “So he answered the phone and said, ‘Hey, you’re getting called up.’ And I said, yeah, whatever.” After making manager Terry Collins prove it was actually him, and getting a legitimate reason why he was getting called up now (catcher Don Slaught hurt himself in that night’s game), Banister finally believed him and took the first-class flight from Buffalo to Pittsburgh.

One at-bat and two games spent on the bench later, Banister was in the dugout when he saw pitcher Bob Walk pull a hamstring rounding third base. “I felt everyone’s eyes in the dugout looking at me.” The team would need the roster spot for an extra pitcher. He was on his way back down. (Yes, in first class again.) He continued to play in the minors, in winter ball, and in the Dominican Republic before elbow reconstruction surgery effectively put an end to his career in 1991. As part of his rehab he was asked to help coach the Double-A team. “And I just fell in love with it.”

Since our conversation, Banister has been promoted to bench coach for the Major League team. With 25 years logged in the organization, if the Pirates play poorly enough to force a coaching change in the near future — a likely scenario since, you know, they’re the Pirates and that’s what they do — don’t be surprised if Banister’s in a new, more exclusive, club in addition to the fraternity of Cup of Coffee players: Major League managers. And, when that happens, you can go ahead and throw him in the book of Great Life Lessons, his entry focusing on how to turn a horribly wrong into a perfectly right.

***

On September 18th, 1892, a man named “Higby” started in right field for the Brooklyn Atlantics. He had three defensive chances, converting two and erring on a third. At the plate, he went 0-for-4. Any other information about him has been lost to time.

Rick Paulas is a White Sox fan.