Know Your Internet History! A Chat With Jennifer Sharpe, Early Web Aggregator

by Mark Allen

The unexamined internet is not worth linking. As the early internet was new and exciting, so many early websites tended to be about the most new and exciting thing at the time: that is, the internet. Or more specifically, about pointing the way to other things on the internet that weren’t typical, boring or commercial (unless extremely or ineptly so). By nature, websites are aggregates of other pieces of the web, and early websites that curated links to other things — done well — rose to the top, naturally selecting themselves as a classic web style (a style that was a forerunner of blogs, a harbinger of social media). So, who were these early aggregators of the internet?

One of the most fondly remembered was SharpeWorld.com. Run by artist, writer and radio journalist Jennifer Sharpe, the site combined its wry original content with a regularly updated assortment of links to peculiar, great content elsewhere. It utilized white space well, was succinct, and looked “un-internet” (in its time). I chatted with Jennifer about the website, which she launched in 1999 (now offline), and what she thought, back then, the future of the internet would be.

Website: SharpeWorld.com

Date created: October 17th, 1999

Wayback Machine earliest archive: May 19th, 2001

Internet History Relevance: link curating, internet aggregation, the internet as a museum for real world discoveries, the internet as a museum for the internet, pre-blogs, baldness, use of white space

What were your pre/non-internet inspirations?

Probably my parents’ cartoonist friend Hap Kliban, aka B. Kliban, who drew all those cat cartoons in the 70s (the cat in the Converse sneakers, the cat playing ukulele and singing “how I love to eat dem mousies”) They were old beatnik friends from North Beach in the early 60s. When we’d go to his house, he’d lend me his fountain pen and we’d draw together. His cranky stoner view of the world turned banality into something strange and funny. The feeling of drawing with him and getting to use his pen sparked something in me that later resulted in SharpeWorld.

Did you have any ideas about doing these things publicly before the internet came along?

In my teen years and up into my early 20s (the early 90s) I wrote and recorded a lot of instrumental music at home, but was too self conscious to play any of it live. Although I was the bass player of a punk band when I was 13. We were called “Atrocity.”

I also studied photography at Sarah Lawrence (with Joel Sternfeld), and worked for a wonderful curator named Marvin Heifermann. But ultimately, the elitism of the NYC gallery scene grossed me out. When the web came along, it felt like such a democratic and public creative space. Everything that galleries were not.

Do you remember the first inspiration where you thought, “Hey, I should make my own webpage!”

No, SharpeWorld was totally accidental. I had been working as a web designer and hated the web. I couldn’t figure out what to do with it. I had worked at a small web design “boutique” (Fullerene) and had gotten fired. I wasn’t coming up with good enough concepts. When the boss fired me, he brought up how I’d made a website for the band Folk Implosion, which I saw as my masterpiece. It was based on the premise that the web had been vandalized and was dysfunctioning. There were bullet holes in the pages showing the html code underneath. Lots of blinking eyeballs gifs taking over pages as though viral activity had taken over.

Wow!

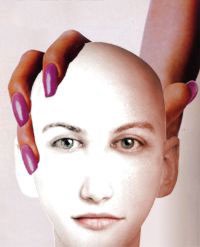

According to the boss, “it wasn’t the direction the company wanted to go in.” So from the humiliation of being fired, mixed with the exasperation of not feeling comfortable in LA yet (I had only been here a year), I had an excess of creative and emotional energy that somehow lead to me shaving my head (although not entirely on purpose). And that experience is what triggered the beginnings of SharpeWorld.

Since I didn’t want to shock my friends by showing up with a bald head on their doorsteps, I put up a web page showing a photo of how I looked bald. I’d written a blurb about being a newly bald white woman and embedded hyperlinks to things I’d found on the web that related to my emotional state in some absurd way. The few friends I’d sent it to wanted to watch my hair grow out and hear more anecdotes. I ran into one of them on the street and he asked when I was going to update my “website.” I was like, oh, I’m doing a website now? Ok.

Where/how did you learn to build with raw html? Did you use “frames?” Did you go to a bookstore and buy a book on it?

I had to learn html when I started freelancing. I had a shelf of Visual Quickstart Guide books and watched lots of Lynda.com DVDs. As far as using frames goes, they felt like an unresolved question for a long time. My frustration with the disappointing cross platform performance of nested frames is probably what turned me against frames for good. I ultimately became a big fan of the no-frills Craigslist school of design.

How did you picture Sharpeworld before setting it up?

For my professional jobs, I’d comp out websites, but SharpeWorld was the opposite. It was just an impromptu thing. SharpeWorld was my rebellion against my web design career.

The thing I noticed about your site when I first saw it in the 90s was the three-column layout. I had never seen that before. How did you do that? Code?

I got the three-column idea from the site Coudal Partners, who I felt very inspired by, and competitive with.

Was there a different Sharpeworld “look” before that one?

Yes, involving frames. The thin upper frame had a nav with a few pull down options, and the whole lower frame had a big head artwork collage that got swapped out with content. Ultimately, I got rid of the frames and adopted the 3-column design, because I wanted the front page to feel more cozy and busy, like you’d pulled up to a great garage sale, and everything was there all at once.

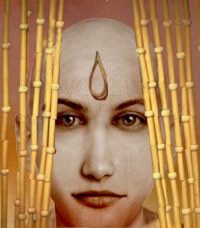

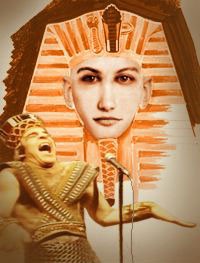

Please explain your intentions with the ever-changing “Sharpeworld bald head” logo.

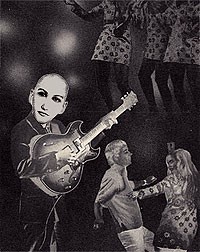

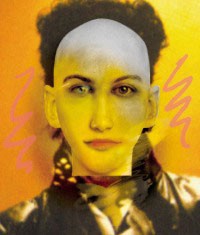

The head logo/icon was a self-portrait I made from memory, using police forensic portraiture software. When I made it, I wanted it to be as if I were sitting at the precinct, reporting myself to the forensic artist.

I made it to replace the photos of me and my shaved head I’d had on the early version of the website, made for friends. After a small write-up in Wired came out, I felt weird and vain having a website about myself. That’s when I decided to put up the head icon, and created a more anonymous, diffused, magazine-y/museum-y, less personal site. Although it became even more personal in other ways, insofar as it was much more creatively satisfying. The head icon gave voice to something in me that hadn’t had the chance to speak before.

When I made the head icon, I wanted it to feel authoritarian, vacuous, self involved, yet benevolent. Creating collages around it, putting the head in different environments, were usually ways to play with ideas or feelings I had at the time. They were visual conversations I was having with myself, though sometimes they referred to things anyone could relate to, like holidays, or something going on in the news.

Your site seemed to be about archiving things you’d found that were interesting, whether they were from the real world or from odd places online. What made you want to share these things?

Since we’re wired as human beings to be hunters and gatherers, when the internet came along, it felt like an exciting new huge arena to hunt and gather — and share — nuggets. Posting things like the Hal Morris promotional museum, The Kriegsmann File of discarded headshots a friend found in an LA dumpster, an archive of WET magazine, the pre-rock video jukebox Scopitones, etc., felt like an involuntary impulse. Back before the internet, it was so much fun to discover obscure bands and share them with your friends. If you discovered something everyone else loved, then you were the coolest. Now everything gets discovered so fast, nothing stays hidden. Maybe that’s a good thing? I don’t know.

What made you want to start featuring to the Scopitone videos?

I couldn’t believe no one seemed to know about Scopitones when I discovered them! What a strange portal into another period of time. Such campy, dreary, surrealistic films. Plus the story behind them — from Debbie Reynolds involvement to probable mob connections — tells a great dimension of the American story you wouldn’t see anywhere else. Posting them to the internet was like remotely exploring an underwater wreck.

One thing I loved about early Sharpeworld was your Celebrities of Real Estate feature, which highlighted good/bad realtor promotional sites. What lead to that?

Personal branding was so funny to me, especially when I first moved to Santa Monica. Aspirational realtors with their headshots and mottos stood out as something so LA. It also reminded me of people on the internet making home pages for themselves, so to post the Celebrities of Real Estate seemed like a natural internet match. One of those things that seemed funnier on the internet than it would have elsewhere.

What kept you going when there was very little like you on the internet?

People would sometimes say disparaging things to me about doing a website, like, “somebody’s got too much time on their hands.” But I never saw it as a waste of time. I wasn’t doing it for a sense of belonging, I just loved discovering things and hoping they’d catch on and travel across the internet. At that time, the internet felt finite, but like it was on the edge of something infinite. I was addicted to watching it grow and change and didn’t care if there was anyone else like me on the internet or not.

I noticed your site went through several changes in the late 90s, early 00s, then it shut down. Then it came back years later with a different, very minimal design. Shortly thereafter it went away for good. Can you describe your motivations during these different periods? Positive and negative?

I got bored. I started to feel trapped by the SharpeWorld aesthetic and how meaningless it had come to feel, like it was just weirdness for the sake of weirdness. People visiting were hungry for more links and that made it feel more like an obligation than an exploration. At the same time, I’d started doing radio stories and loved being outside in the real world. The simplicity of exchanging energy in a direct way, person to person, voice to ear, appealed to me more than clicking around on the internet searching for the next obscure thing.

People would sometimes talk me into doing the site again and I’d feel guilty and curious enough to do it, only to discover I was still bored with the internet. Looking at things like vintage vacuum cleaner museums had come to annoy me. Also, the internet had started to get really vast, and sites like BoingBoing had gotten so good, I didn’t see the point in doing SharpeWorld anymore.

You were often linked on sites like BoingBoing, MetaFilter and Slashdot. Did you like when this happened? Were that other sites that used to nod to you with a link that you preferred?

Yes, I would gloat about it to my parents. I liked getting on BoingBoing and MetaFilter most, that really made me feel like I’d hit the big time and was in touch with “the zeitgeist.” But the satisfaction of it was nothing that ever translated meaningfully into my real life. I couldn’t brag about it to friends; it didn’t mean anything to anyone in my real world; it didn’t translate into money or teaching gigs. A few years ago, I met one of the BoingBoing editors at a party and he had absolutely no interest in who I was or in talking to me. It’s weird to have created something that had a certain degree of success but that in no way translated anywhere outside my own head.

Looking back on when you first began Sharpeworld, how do you feel about it now, thinking about how it played out during its run?

I think it was amazing. What an honor that I got to experience the early web from such an inside perspective. I saw my audience as being people who were stuck at work in cubicles, bored, like I had been for so many years when I’d lived in NYC. That I could make something for them that was also therapeutic for me, was a great thing to be a part of.

What are some of the things you feel would have been easier with your site today that you couldn’t do in the late 90’s/early 00’s?

Content management by hand was a huge pain in the ass.

Would Sharpeworld even be possible today?

No!

What do you think today’s “social media”-based internet?

I think it’s a miraculous dream come true that you can be connected to almost every single person you’ve ever known, and keep up with them on a daily basis. But recently, I finally got exhausted by it. I deactivated my Facebook account about a month ago.

All the self-promotion was starting to feel too gross. I got embarrassed by reading peoples’ yoga epiphanies, and felt offended for my friends’ kids who are being exploited in the photos shamelessly and incessantly being posted of them. It depressed me to see how someone can only talk about their kids and the music they listened to in high school. I’ve gotten so tired of nostalgia. The past feels like it’s become a dangerous burden. Maybe I’m done with nostalgia and have finally entered into the age of delete.

Who do you think are some other unsung heroes of the early internet?

Ben Benjamin is my big unsung hero of the internet. He did a blog called Misterpants that was so smart and funny, but before that, he also did a brilliant website called Superbad that changed how I saw the web. It was the first website where I thought, here’s someone making art on the web, exploring it as a creative platform.

Superbad was very mysterious, had no nav, no information about the site, and exploited the sense of rabbit hole discovery that the web is so great at providing. The look of it reminded me of color xerox new wave art from the late 70s, but with a distinctly 90s design feel. It had pages that would do beautiful fluttering unpredictable things, before throwing you elsewhere.

The person behind it obviously had advanced javascripting abilities. I imagined it was made as a design or advertising company’s creative in-house side project. It was just a coincidence that I happened to later become friends with Ben in LA. I was stunned to learn that this little guy with an Abraham Lincoln beard was actually the mysterious genius behind Superbad.

Sharpeworld is down, with bits and pieces archived online in places like Wayback Machine, etc. In the future, when you’re telling younger people “I used to have a website in the early days of the internet,” how will you share it with them?

No one is ever interested when I tell them about SharpeWorld. It’s an embarrassing thing to try to explain. “I did a website that was kind of popular…” I can see by peoples’ expressions that they think I’ve got delusions of grandeur about myself, or their eyes gloss over as if to say, what could be a more boring than talking about an old website? But in the future, maybe people will want to go back and study this period of time when no one knew how to monetize the internet and didn’t know what else to do but make art with it.

Previously: A Chat With Rob Cockerham, Early Web Prankster and A Chat With Rex Booth, Early Web Cam-mer

Mark Allen is a writer and performer living in New York. He has been on the internet way too long.