The Inconvenient Astrologer Of MI5

by Emma Garman

In the summer of 1941, delegates at the American Federation of Scientific Astrologers’ convention in Cleveland, Ohio, listened to a keynote address from an astrologer named Louis de Wohl. The bespectacled German-Hungarian — late thirties, rather corpulent, flamboyant in dress and confident in manner — told his rapt audience that Hitler was operating under advice from “the best astrologers in Germany,” who had plotted out the course for Germany to attack the U.S. The invasion, it seemed, would occur sometime after the following spring, once Saturn and Uranus, the two “malefic” planets, had entered Gemini, America’s ruling sign: “America,” he warned, “has always been subject to grave events when Uranus transits Gemini.” De Wohl’s professional assessment, nonetheless, was that the stars portended eventual disaster for Hitler. “We can’t predict a date for his defeat,” he said, “but if the United States enters the war before next spring, he is doomed.”

What no one realized was that de Wohl’s lecture was pure propaganda from the British government, which was attempting to drag the Roosevelt administration into WWII by any means necessary. De Wohl, who was employed by SOE (Special Operations Executive, the wartime sabotage unit), had been dispatched with instructions to present himself as a renowned astrologer with no connections to Britain, and to undermine America’s belief in the invincibility of Hitler. As the spy novelist William Boyd put it in a 2008 radio interview: “At the time, there was a perception of American people, in the minds of the British Security Services, that they were more gullible than us Brits.”

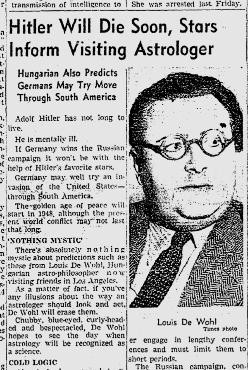

De Wohl’s visit to Cleveland was part of a nationwide tour of talks and media conferences. He was interviewed by the New York Sun, which ran a story with the headline “Seer Sees Plot to Kill Hitler,” detailing de Wohl’s predictions that Hitler would be “done away within a year.” In an interview with the New York Sunday News, headlined “Hitler’s Stargazer Sees Heavenly Stop Light,” de Wohl revealed that he’d obtained a letter written by Hitler’s top astrologer, Karl Ernst Krafft, who confessed that in his opinion, Hitler wouldn’t win the war and, indeed, would “suddenly disappear.” The Los Angeles Times published a front-page report on de Wohl’s forecasts, the most important being that unless America joined in the effort to defeat the Nazis, Germany would invade the country via Brazil.

De Wohl didn’t shy away from making more immediate predictions, either. He announced that an important ally of Hitler, one who wasn’t a German or a Nazi, would go insane within ten days. Lo and behold, the press soon reported that Admiral Georges Robert, the Vichy High Commissioner of the French West Indies, had lost his mind and could be heard shouting and screaming all night. Supernatural corroboration of de Wohl’s prognostications came from far and wide: a Cairo newspaper published some prophesies from an Egyptian astrologer that eerily tallied with de Wohl’s description of Hitler’s downfall, as did the publicized visions of a Nigerian priest and the soothsaying of a Sierra Leonean stargazer.

Little wonder, then, that the public started to believe in de Wohl; they couldn’t possibly have known that the press reports were planted by the British and the letter from Krafft was forged. It helped that American attitudes to astrology were less skeptical then, or so the ease with which de Wohl’s predictions achieved credulous media coverage would suggest. He certainly talked the talk: Hitler’s death was assured, he explained at a New York press conference, by Neptune entering his house of death at the same time as his progressed Ascendant conjuncting his natal Neptune, a set-up to be triggered by transiting Uranus. That Hitler would be alarmed by such confident prophesizing of his demise, since he supposedly believed in astrology, was a nice side-benefit.

***

De Wohl was in fact a practicing astrologer: in his 1937 memoir, I Follow My Stars, he describes the turning point of his life when, as a young novelist in Berlin, he meets a man whose ability to cast accurate horoscopes is so impressive that de Wohl himself is lured into the study of astrology. The relentlessly cheery and self-assured tone of this memoir, which portrays de Wohl as a plucky adventurer with prodigious creativity — he claims to have written his first novel at the age of 21, in a few weeks, while recovering from an illness — leaves the reader uncertain as to whether his “conversion” to astrology was genuine or merely a welcome opportunity for financial and social advancement. Either way, after leaving Germany in 1935, likely a necessity due to his being at least part Jewish, de Wohl settled in London, developed a reputation in powerful circles as a skilled fortuneteller, and was able to charge 30 guineas (more than $1000 in today’s money) for a horoscope.

The nature of his clientele, which included foreign diplomats and military personnel, drew the attention of MI5, and senior intelligence officers decided it would be useful to recruit him. “As it is often of considerable interest to know who is consulting an astrologer and for what reason,” wrote a Major Gilbert Lennox in a letter to the MI5 War Office, “and it is sometimes even more interesting to hear the advice which the stars give, I have made a private arrangement by which I get reported to me the names and details of Louis’s clients.”

De Wohl, meanwhile, was persuading the powers that be of the vital contribution he could make to the war effort: claiming that the dates of all Hitler’s major coups were related to planetary aspects, he proposed that by reading the horoscopes of the Fürher and his henchmen, he could replicate whatever astrological advice the Third Reich was receiving, thus gaining much-needed insight into their confoundingly erratic military strategy. With this dubious brief, de Wohl was set up as a one man department: the “Psychological Research Bureau” occupied rooms at the Grosvenor House Hotel on Park Lane, where de Wohl prepared astrological reports on German military high-rankers.

***

According to Ellic Howe, who at the time was employed by PWE (the Political Warfare Executive, a clandestine propaganda unit reporting to the Foreign Office), none of the real spooks took de Wohl’s reports seriously, but they realized that his astrological knowledge could be a worthwhile propaganda tool.

One scheme was the “revival” of a defunct German astrological magazine, Zenit, to be edited by de Wohl and distributed in Germany “by surreptitious means.” Under the supervision of PWE chief Sefton Delmer, the magazine made predictions tailor-made to frighten the German forces. For example, a highly successfully German naval commander, Reinhard Suhren, was shown to have such a lucky horoscope that his subordinates would not face danger so long “as they are personally near him.” Suhren, however, was soon promoted off his boat — a detail that British intelligence presumably knew in advance. Zenit’s sixth and final issue also revealed that SS leaders would soon betray Hitler. Lee Richards, in his book Black Art: British Clandestine Psychological Warfare Against the Third Reich, quotes Delmer on the experience of working with de Wohl:

As I nervously put forward my views on what I rather hoped the stars might be foretelling, he frowned at me with terrifying ferocity, as though to reprove me for my infidel cynicism. Then he would grab up a handful of astrological charts from his Chippendale escritoire and make some rapid astral calculations. This done, he would turn once more to me, his frown now relaxed into a patronising smile. With the air of the master addressing a promising neophyte he would say in his guttural Berlin English: “How do you do it my friend? It is most extraordinary. There is something very much like you say. In the…” Then there would follow some, to me completely unintelligible, jargon about constellations, aspects, signs and so forth. But I had to keep the straightest of faces when making my suggestions. For my astrologer always insisted that he would under no circumstances be prepared to prostitute his sacred knowledge to purposes of subversion, much as he abhorred Hitler and what he stood for. It was simply a most fortunate coincidence that what I suggested so often fitted in with what the stars did indeed foretell.

Particularly useful was Zenit’s accounting for the recent success of Allied naval forces in ambushing German U-boat submarines — in reality achieved thanks to MI5’s cracking of the “Enigma” military code — by stressing the importance of heeding astrological factors if an “almost magical attraction for enemy cruisers and destroyers” is to be avoided.

Indeed, one of de Wohl’s most valuable roles for British intelligence was as a front for information obtained by intercepting Enigma transmissions, which were used by the German High Command to convey orders. Once cryptanalysts at the famous Bletchley Park HQ had cracked the code, it was vital that no one knew about the enormously powerful tool at their disposal. So when passing on intelligence to field commanders, a nameable source was de Wohl’s Psychological Research Bureau — and de Wohl, never the most modest of men, could brag about how his predictions were defeating the enemy.

***

It was de Wohl’s obnoxious personality that, in the end, led to his ousting from the sphere of influence whose prestige he so enjoyed. He had even persuaded the colonel of a military intelligence department to confer upon him the rank of Army Captain; despite a promise of a total secrecy, he would “strut around” London decked out in military garb. An acquaintance has described seeing de Wohl in his “splendid officer’s uniform” for the first time: “Louis was like a boy who had just received his Christmas presents. He stood up, he sat down, stood up again, walked around the room and looked into a large mirror in silent admiration.” (De Wohl’s love of costume extended to a penchant for cross-dressing, as his handlers gingerly noted.)

Apparently incapable of the discretion his position required, de Wohl was soon regarded in as a thorn in everyone’s side — a note in his MI5 file, which was declassified in 2008, says: “He is much given to boasting, particularly about his connections with the War Office, Admiralty, etc. and would appear to an unsuitable type to be employed in any kind of secret activities.”

Another concerned letter, dated May 1943, states: “I feel that there have now been so many indications that de Wohl is an indiscreet talker and a bumptious seeker after notoriety, that it would be insufficient merely to place him on the Unemployed List of the Army, and that he should be retired altogether.”

The only problem was, exactly how could they quietly retire the man who had styled himself as Britain’s State Seer? An aggrieved de Wohl was definitely not an appealing prospect, as had long been clear. When he returned from the States shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor — an event that, obviously, rendered his mission redundant — an MI5 officer wrote that de Wohl could easily “become a very dangerous enemy owing to the considerable influence which his charlatanism enables him to exert over the superstitious in high places.” Three options to “dispose of him” were considered, including sending him away to live in a remote part of the country and restricting his movements. The other two options were ominously redacted.

In I Follow My Stars, de Wohl recounts visiting India in his early thirties and meeting a psychic yogi who predicts he will die at the age of 61. Actually, he didn’t live quite that long, but he wasn’t bumped off in his prime by MI5 either. Instead he gradually faded from prominence, converted to Catholicism and was rewarded for his services to the Allied cause with the British citizenship he dearly coveted, although he remained under MI5 surveillance until the end of 1945. After the war, de Wohl became a popular and prolific author of novels about the lives of saints, including Joan of Arc, St. Benedict and St. Francis of Assisi. His decade-long obsession with astrology was forgotten and, as it turns out, his entire career in the spy world was based on a falsehood anyway. While some of Hitler’s henchmen, including Himmler, had some belief in astrology, it was officially banned in Nazi Germany and the man identified by de Wohl as Hitler’s personal astrologer, Karl E. Krafft, would die in a concentration camp. “Hitler regarded astrology as nonsense,” confirms Christopher Andrew, official historian of MI5, “but the belief that he really paid attention to horoscopes entered Whitehall.” It’s a historical misperception that endures to this day, thanks in no small part to the strange, unscrupulous and thoroughly mercurial Louis de Wohl.

Related: The Vicious Trademark Battle over ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’

Emma Garman is Sagittarius with Leo Rising and a Gemini Moon. She writes this site’s British Manufacturing column.