Psychological Risks Associated With Pencil Sharpening, From David Rees' 'How To Sharpen Pencils'

by David Rees

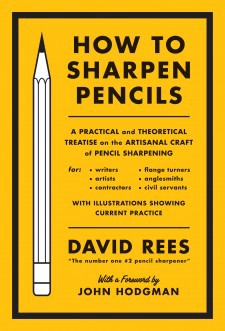

An excerpt from David Rees’ newest book How To Sharpen Pencils, out today from Melville House. The book’s official launch happens at Barnes & Noble Union Square tomorrow night at 7 p.m., at an event featuring Eugene Mirman, Stacy London and Sam Anderson.

Every aspect of pencil sharpening includes its own suite of pleasures and anxieties. The pleasures should be familiar to you; we turn now to the anxieties.

Although sharpening a pencil is usually a psychologically rewarding experience, resulting in feelings of accomplishment and serenity, it also entails psychological risks. It is your professional and personal responsibility to be aware of these risks, and to actively discourage their flourishing in your practice.

DISAPPOINTING THE CLIENT

The greatest anxiety, at least for me, is disappointing my clients. Whether you’re sharpening a pencil in front of a crowd or alone in your workshop for a distant stranger, the weight of expectation can disturb an otherwise balanced mind.

It is during these paid “gigs” that your relationship to your pencil sharpeners is most like that of a musician to his or her instrument. It is incumbent on the performer to ensure his or her instrument is operating at maximum capacity. This means, of course, tending for it; tuning it; maintaining and optimizing its functionality; and treating it with the respect it deserves — while ensuring others do as well.

The more care you invest in your pencil sharpening tools, the more familiar you are with their strengths and their idiosyncrasies, the more confident you can be during their use. This will in turn reduce your anxiety — freeing up space in your consciousness for more profitable thoughts.

Keep your blades sharp. Keep your burr cylinders clean. Keep your eyes on the task at hand. This will go a long away towards keeping your demons at bay.

ANXIETY OF THE UNKNOWN: THE UNSHARPENED PENCIL

Even if you are confident about your practice, famil¬iar with your tools, and certain of your ability to make the best use of them, there is yet another element of the pencil-sharpening experience to consider. It is the one clients pay the most attention to, with good reason — for this element is the sharpener’s raison d’etre: the pencil.

Ironically, the client’s pencil is simultaneously the most crucial element of the job and the element you will be least familiar with — for (unless you’re renewing a point you’ve previously sharpened) you will be approaching it for the first time. This is why it’s crucial to have confidence in your ability to size up any pencil the client offers, or confidence in any pencil you yourself provide.

As we’ve discussed before, an easy way to reduce anxiety and improve the chance of sharpening success is to make sure the pencil’s shaft is straight, the graphite is centered within the wood, and the unsharpened top is free of paint. It’s also worth reminding the client that a poorly manufactured pencil can only play host to a point of mediocre quality; we cannot expect a five-star meal from a one-star restaurant. Saying this in a loud voice will comfort the client — they will know they are in good hands. Your confidence will be bolstered in turn.

PERFORMANCE ANXIETY: THE LIVE PENCIL-SHARPENING EXPERIENCE

Any professional pencil sharpener worth his or her salt will have road stories about hecklers and unforgiving customers who seem incapable of accepting that every pencil is different, and some will carry scooped collars or other irregularities to their grave. We must not be discouraged by obnoxious reactions to our craft; instead, record any wounding taunts or sarcastic remarks in your log along with a physical description of their authors. Then commission a comedian or bartender to compose witty responses and mail them to the offending party.

EMOTIONAL RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH DIFFERENT PENCIL-POINTING TECHNIQUES

As the reader now knows, each method of sharpening a pencil produces a different point — a result of its unique technology and operation. Is it any wonder, then, that each method is also attended by its unique forebodings and disquietudes? Below is a partial list of the emotional risks associated with particular sharpening techniques.1

Single-Blade Pocket Sharpener:

Any discussion of the psychological risks associated with single-blade pocket sharpeners must begin with the tyranny of the irregular pin tip. The agony of removing a pencil from the device, only to find an errant filigree of graphite branching away from the point’s end, will be a familiar sensation to the novice — and is hardly unknown to the professional.

Fortunately, an irregular pin tip is less a verdict of one’s failures as a craftsman and human being as it is an argument for further diligence and research. One of the many psychological benefits of maintaining a pencil-sharpening log is the comfort of actionable data it provides. If you find yourself producing irregular pin tips with unseemly regularity, simply review your log for the average number of rotations and applications of force you apply with a single-blade pocket sharpener, and adjust accordingly.

A second psychological risk associated with single-blade pocket sharpeners is the terror that they will be misplaced and lost due to their diminutive size. I myself used to suffer from this distraction until, recalling the age-old advice of finding “a place for everything, and everything in its place,” I constructed a pocket-sharpener compartment system for my tool kit, and pledged to return any pocket sharpener to its tiny cubicle as soon as its job was finished. An afternoon’s work served to eliminate a year’s worth of worry. Such is the nature of investing in one’s well-being — the dividends are exponential, if not infinite.

Hand-Crank Sharpeners (Single- And Double-Burr):

The reader may insist that hand-crank sharpeners, being the most consistent and predictable of our pencil-pointing devices, are incapable of causing psychological distress. As counterargument I offer two difficult situations the hand-crank user may encounter:

1. Removing a pencil from a hand-crank sharpener for inspection, only to find that the graphite point has broken off inside the device, leaving you with a “hollow collar” — a finished collar with a hole where the graphite should be.2 The unhappy absence where one was expecting abundance may well trigger unwanted associations with financial, intellectual, and romantic aspects of your own life. Ignore them. Amputate the empty collar, clear the sharpener’s burrs of the forfeit point, and set course for the future abundances that are your due.

2. Inspecting a hand-cranked point, determining it isn’t sharp enough, and then reinserting it into the sharpener, only to break the point upon its reinsertion — thereby destroying your investment of sweat equity by your own hand. This phenomenon, perhaps the most frustrating in the trade, is known as the “Malleus Maleficarum,” because, like the 15th century witch-hunting text for which it is named, it suggests the existence of satanic conspiracy.3

Again, consider this unholy accident an opportunity for recalibration of your technique: The next time you reinsert a semi-sharpened pencil into a hand-crank sharpener, do so with greater delicacy so as to minimize the chance of breaking the point against the static burrs. I have little doubt your odds of catastrophe will diminish.

Knife:

Of all pencil-pointing technologies, surely the knife promises the deepest wellspring of potential emotional hazards, as its threat is simultaneously literal, archetypal, and Freudian. (Those suffering from aichmophobia4 are reminded that there is no shame in omitting knives from their practice.)

The pocketknife in your tool kit may host an additional profusion of anxieties, if, like mine, it belonged to your late grandfather — a successful research chemist, amateur astronomer, and woodworker who lived through the Great Depression, built his own telescope, voted Republican, and kept his hair in a neat buzz cut. You may find it difficult to use the tool for your pencil-sharpening business without feeling a clammy apprehension that somewhere, a ghost is rolling his eyes at you. No matter: Though ours may not be the “Greatest Generation,” we can still insist on fumbling towards greatness on our own terms.

THE IMPORTANCE OF MAINTAINING A HEALTHY ATTITUDE TOWARDS ONE’S PRACTICE IN THE FACE OF BROKEN PENCIL POINTS, PHYSICAL EXHAUSTION, SOCIETAL DISAPPROVAL, SEXUAL IMPOTENCE, AND FINANCIAL RUIN

In the end, even the most accomplished pencil sharpener must concede that absolute perfection, while an appropriate goal, is rarely attained. Pencil sharpening takes place in the unforgiving glare of the physical world, and is subject to the same contingencies and calamities that bedevil all things material.5 Happily, however, like any earthly specimen, our practice (whether “sweet, sour; adazzle, dim”) may thus lay claim to those glories of “pied beauty” celebrated by Gerard Manley Hopkins.6

We must learn to live with — perhaps even savor — the uncertainties and imperfections that attend every pencil point, even as we continue to strive for their ideal form. This is not an admission of futility so much as a considered reflection on the vagaries of human experience and the importance of appreciating one’s circumstance even as one seeks to improve it.

It is in this spirit that I invite the reader to heed the following words, not in my capacity as a pencil sharpener, but as a friend:

The only perfection available to you without compromise is that of intention and effort. If you endeavor to be the best pencil sharpener you can be, and tailor your actions accordingly, you can be certain all else will be forgiven in the final accounting.

With these words I have solved all psychological problems.

1 Specific antique sharpeners may also provide succor.

2 Also known as a “headless horseman” or a “Louis XVI,” a hollow collar is most often caused by internal breakage of the pencil’s graphite core somewhere below the collar top. Unless you make a habit of throwing pencils against the wall before sharpening them, it is not your fault. Few things are.

3 Although the Malleus Maleficarum pre-dates the modern pencil by almost 100 years, a sufficiently metaphorical reading of the following passage suggests the Devil’s hand is indeed to blame when pencil points are removed by hand-crank sharpeners:

“Here is declared the truth about diabolic operations with regard to the male organ. And to make plain the facts in this matter, it is asked whether witches can with the help of devils really and actually remove the member, or whether they only do so apparently by some glamour or illusion. And that they can actually do so is argued a fortiori; for since devils can do greater things than this . . . therefore they can also truly and actually remove men’s members.”

4 Per Wikipedia, aichmophobia is “the morbid fear of sharp things, such as pencils, needles, knives, a pointing finger, or even the sharp end of an umbrella . . .” (Emphasis added, to argue that the ranks of top-seeded pencil-sharpening aichmophobes may be thin indeed.)

5 For instance, as I finish this chapter late at night, my sedan’s car alarm keeps going off — to the delight of my neighbors, no doubt. (One of whom is a bald, burly mechanic and one of whom is a tattoo-covered prison guard [female], both of whom could probably break a bundle of pencils with their bare hands.) However, as automobiles are material objects, we must learn to live with their shortcomings, as I will remind my neighbors in the morning before being beaten to death.

6 Glory be to God for dappled things —

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced — fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

David Rees first came to fame as the author of Get Your War On, a Bush-era comic strip composed from clip-art that he emailed to friends. It was eventually serialized by Rolling Stone magazine, collected into three successful books, and turned into an off-Broadway play. He is also the author of the workplace satire My New Filing Technique is Unstoppable. He lives in Beacon, New York. This is his pencil site.