The Frightening Politics Of Hungary's House Of Terror

The House of Terror opened in 2002. Since then, it’s become one of the most popular tourist destinations in Budapest. It’s a museum, and it presents the last sixty years of Hungarian history through a mix of exhibits and multimedia displays. It’s also a memorial, dedicated to “the victims of both the Nazi and the Communist terror.” The building that houses it, an elegant 19th century villa, was once the headquarters of both the Arrow Cross, the Hungarian Fascist Party, which ruled Hungary for a few bloody months in 1944, and of the Communist Secret Police, up until the 1956 revolution. Thanks to the building’s history and to the dungeons in its basement, which were used to hold political prisoners and host executions, the museum is itself a witness to old crimes. And maybe associated with new ones, as well: the House of Terror was originally built as pet project of Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz Party, who are currently engaged in an assault on Hungarian democracy.

The building is marked off from the neighboring townhouses by a giant steel blade projecting from the roof, which has the word ‘TERROR’ cut out of it in large stencil letters, along with the arrow-cross of the Hungarian fascists and a communist star. During the day, the word and the symbols creep along the side of the building as shadows. The sense of jarring displacement continues once you’re inside, as you walk through a series of frightening, and occasionally baffling, multimedia tableaux, with video screens jumbled alongside nooses, crypts, tanks and illuminated crosses. It feels like a movie set — and in fact, it was designed by Attila Kovács, a movie set designer whose credits include István Szábo’s Oscar-winning Mephisto.

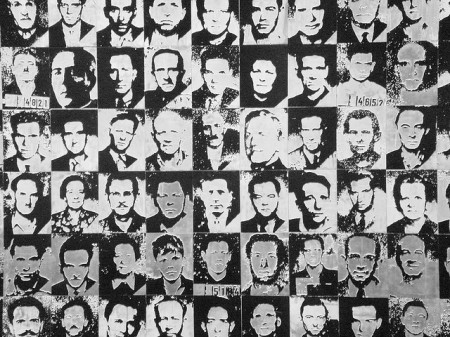

The first room bombards you with noise: Hitler speeches, wailing women, pounding Death Metal. The next room stages a silent banquet, one presided over by a mannequin of Ferenc Szálasi, the puppet dictator installed by the Nazis at the end of World War II. Szálasi’s features are projected onto a blank head, as a movie is onto a screen. Further on, there’s a rotating torso clad on one side in the uniform of the fascist Arrow Cross, on the other of the Communist secret police, insisting in a graphic way that there was no difference between the two regimes.

Another room, carpeted in a giant map of the Soviet Union, mimics one of the Soviet boxcars that transported Hungarian prisoners to Siberian gulags. In place of windows, it has video screens. The screens play interviews with prisoners, but at intervals they all switch abruptly to scrolling images of the flat, frozen countryside — giving the impression that the room is suddenly lurching into motion. Other rooms go even further in their efforts to disorient and confuse: a collection of brightly-colored, oversized Communist-era household goods; a cold, empty meat-locker; a closet containing only a pair of boots and a truncheon; a labyrinth made out of white wax bricks.

The museum presents history as nightmare, something that isn’t a narrative at all but a string of ominous sensations. Like a haunted house, it’s able to evoke genuine dread while at the same time causing the mind to bubble with unexpected associations. This is most true of an exhibit which I took to be the museum’s heart: a room containing a single black, Soviet-issue car, the type that secret police officers used to pick up their victims in the dead of night. The car is obscured behind a diaphanous black curtain, as if too evil to be looked at directly. A spotlight turns on and off intermittently, illuminating the back seat. Upholstered in lush red velvet, the seat glows like a giant heart, beating in a slow rhythm. It looks like something out of a David Lynch movie, like the Red Room in “Twin Peaks” or the Silencio Bar in Mulholland Drive — spaces of impossible, deviant pleasure.

***

The museum is a visual blueprint for how Fidesz, the right-wing party that now dominates the Hungarian political scene, has been busy rewriting the country’s history. And one space where the search for what that history has been is in the museum’s underground: its dungeons.

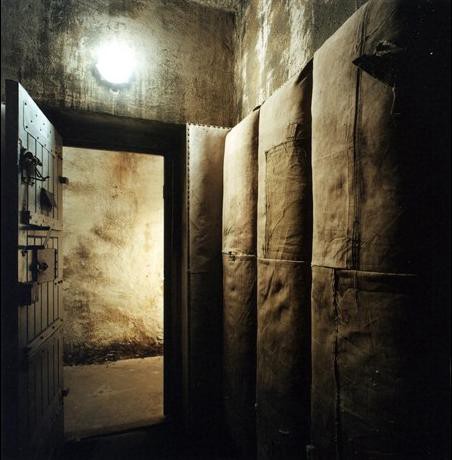

At the end of the main floor, visitors come to the elevator that takes them to the basement, which held prison cells, interrogation rooms, and a secret underground gallows. During the excruciatingly slow descent, a video screen plays an interview with the janitor responsible for cleaning up after the executions. While he gives a grimly detailed account of the precise mechanics of subterranean hangings, a stone-faced attendant on the elevator makes sure no one laughs. When the ride ends, visitors are let loose, to peer at the recreated gallows and explore the secret cells and chambers preserved in all their dank claustrophobia.

According to a museum brochure, former interrogators interviewed during the process of reconstruction insisted that the building had many more underground levels, but excavators could find no evidence of them. It wasn’t the first time they’d gone digging. During the 1956 Revolution, a team of Hungarian revolutionaries searched in vain for a network of subterranean cells housing hundreds of political prisoners. Supposedly, these cells were built by Soviet engineers during the construction of the Budapest Metro. They were also rumored to house barracks for the secret police and machines for disposing of their victims: giant people shredders and vats of acid. Despite days spent digging under the Communist Party headquarters in Budapest with drills and teams of excavators, the team wasn’t able to find anything. In 1993, the first post-Communist government started the search again, drilling 50 feet below ground, but again found nothing.

In a way, excavation is what the House of Terror is all about. It tries to expose a hidden history. As the historian István Rév has pointed out, it’s as if “by holding up the underground, by bringing it to light, they could hope that the whole Communist historical construct, the world that the Communists made, could be undermined.” But exposure goes along with concealment.

Fidesz is led by strongman Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s current prime minister. The museum was built during Orbán’s first term in office, which started in 1998, with 20 million dollars of taxpayers’ money. It opened just before the 2002 elections, when Fidesz was trying to maintain its hold on the government. It was the site of a major rally designed to win voters away from rival centrist parties, at which Orbán announced his vision for the museum: “We have locked the two terrors in the same building, and they are good company for each other, as neither of them would have been able to survive long without the support of a foreign military force.”

The sleight of hand here — equating Fascism with Communism, and dismissing both as foreign intrusions — is typical of Orbán’s rhetoric. It’s also central to the museum’s mission. Its exhibits deliberately avoid making distinctions between perpetrators. They argue that Fascism and Communism both lie outside what Fidesz calls “authentic Hungarian history,” despite the fact that Hungary had its own fascist party and its own Communists. This narrative provides absolution for the worst parts of the twentieth century: since both movements were foreign imports, Hungary bears no responsibility for either the Holocaust or the Gulag. At the same time, it promotes a vision of history in which Hungary is a perennial victim, and Fidesz its long-awaited savior.

***

Over the past year, Fidesz has mounted a sustained attack on Hungary’s democratic institutions. Hungary is not yet an outright dictatorship, but neither is it a genuine constitutional order. Instead, it is a sort of hybrid, somewhere between the post-modern, media-driven populism of Berlusconi’s Italy and the more brutish authoritarianism of Putin’s Russia.

The trouble began when Fidesz won the 2010 parliamentary elections. Armed with a supermajority in parliament (despite gaining only 53% of the vote), Fidesz has moved swiftly to consolidate its power. It has packed the courts with its supporters and turned state-media outlets into party organs. At the same time, it’s forced a raft of legislation that will make effective opposition to its rule almost impossible in the future. These measures include gerrymandered electoral districts, severe limits to the independence of the judiciary and press laws subjecting media to state censorship. Fidesz has also floated a proposal for an amendment (pdf) which would hold the Socialist party responsible for all the crimes perpetrated by the Communist system, effectively outlawing its main competition.

This process culminated with the passage of a new constitution that threatens to make many of these changes permanent. It went into effect on January 1st, and it eliminates many of the checks on political power which are essential to a functioning democracy, leading Kim Lane Scheppele, an expert on constitutional law and a keen observer of the Hungarian situation, to call it an “unconstitutional constitution.”

The new constitution enshrines Fidesz’s particular brand of nationalism in the country’s basic law. The preamble proclaims the state to be the direct inheritor of the Crown of St. Stephen (the historical “greater Hungary” from before WWI, which included much of Slovakia and Romania) and changes the name of the country from the Republic of Hungary to, simply, Hungary. More significantly, it declares that the Hungarian state was not legally competent for a period of more than forty years — from March 1944 to May 1990, the dates when the Germans invaded in WWII and when the first freely elected government took office, respectively. In effect, this strange declaration excises a half-century from the nation’s history.

Most Western commentators on the Hungarian situation have interpreted the rise of the right as a symptom of the worldwide economic crisis. There’s some truth to this: in the 2010 elections, Fidesz benefitted tremendously from anger at the preceding socialist government’s mismanagement of the economy under the. Jobbik, an extreme right-wing party, owes much of its recent success to the precipitous increase in unemployment, especially among the young. But Fidesz and Orbán (the two are inextricably linked: there would be no movement without the man) have been in public life for a long time. The party previously ruled as part of a coalition government from 1998 to 2002, and Viktor Orbán has been in the national spotlight for over twenty years. The party’s current success involves more than a reaction to recent economic discontent. It depends on a belief that is widespread in Eastern Europe: that the Communist past still infects public life, and that the entire political order needs to be upended for this influence to stop. This is the source of the party’s appeal and the driving force behind its radicalism. What Viktor Orbán and Fidesz have attempted isn’t simply a power grab: it’s a political exorcism.

***

It’s often been observed that Hungary’s present problems are rooted in its weak tradition of democratic government. But that isn’t really true — at least, no more so than for most of the rest of the European Union. Like most of Europe, Hungary was run by a right-wing dictatorship, and like most of Eastern Europe, it spent the post-war era as a one-party state. But political tradition is what you make of it. Hungary also has a deep history of representative institutions and radical politics, and a legacy of democratic revolt — most notably the armed 1956 Revolution and peaceful transition from communist rule in 1989. Part of the irony of Fidesz’s rise to power is that it originally belonged to this progressive strain of Hungarian politics. When it began, back in the 80s, it was a youth-libertarian party, part of the movement that toppled Communist rule and explicitly positioned itself as an inheritor of the spirit of 1956. It’s only in the intervening years that it has turned to the authoritarian and nationalist side of Hungarian history as a weapon against an enemy that no longer exists.

On the surface, what the House of Terror presents is a lie: a falsified narrative of Hungary’s history. It’s a spooky, exhilarating narrative, one in which visitors are stuffed in cattle cars, locked in interrogation cells and sent into torture holes — in this way the House of Terror does for the 20th century what hell houses do for hell. But below the surface, the museum communicates a hidden truth about the underside of Fidesz’s ideology of national renewal. Orbàn was right to call it a prison for the terrors of the twentieth century. The real appeal of the House of Terror is subliminal. It speaks a language of pleasure and fear. As an experience, it’s really not about Hungary at all, but about the perverse attraction of totalitarian power.

Jacob Mikanowski writes about art, books and Europe east of Berlin. Photo of museum exterior by the Espino Family, bottom photo by munksynz, both via Flickr; other photos courtesy of the House Of Terror.