Roman, The Billionaire Who Came In From The Cold

Roman, The Billionaire Who Came In From The Cold

by Emma Garman

A series dedicated to explaining Britain’s manufactured celebrities to an American audience.

We must begin today, I’m afraid, by sullying our hands with the unsavory subject of brand association, that ineffable pillar of culture responsible for such teachable moments as the Kardashianisation of Christian Louboutin stilettoes (poor Christian must look at Kim’s plastic parts hovering atop his red-soled nude peep-toes and wonder if it’s all worth it) and Abercrombie & Fitch’s callous proposal that our old friend Mike the Situation be paid not to wear A&F; clothes. So here’s a tricky philosophical conundrum, a Zen kōan for the 1 percent set, as it were: a famous Russian oligarch is casually browsing in his local Hermès, when suddenly and dramatically he’s served a $5 billion writ by his sworn nemesis, with the incident caught on security cameras — dust-up between respective retinues of bodyguards et tout — and instantly reported around the world. Good or bad publicity for Hermès?

Over the years, the French accessories peddler has weathered its fair share of dubious PR, though it is not this column’s place to say whether the nadir was a white Hermès scarf featuring in a Basic Instinct sex scene, Oprah’s accusation of racism or the grim revelation that Posh Spice owns more than 100 Birkin bags. But as for the London Sloane Street branch’s historic participation in what I like to title Roman Abramovich Gets Sued For Billions, Goes to Court, and (Maybe) Gets a Heart: greater advertising than money can buy or, to delicately coin an analogy, a rippling DTF Guido in logoed sweatpants fiasco? Only a tumultuous ride through the Dickensian rags-to-riches tale of Red Rom’s life will qualify us, albeit humbly and tentatively, to judge.

In the weeks leading up to that fateful encounter, Roman had been assiduously avoiding his vengeance-bent enemy. 65-year-old Boris Berezovsky, a pugnacious former Kremlin insider, was granted asylum in the UK around a decade ago after a dangerous falling out with President Putin, and in early 2007 had filed papers at the Royal Courts of Justice asserting that Roman, his one-time business partner, had swindled him out of billions back in the day. But in order for legal proceedings to commence, a writ had to be served, and for six months the two men played cat and mouse, with Boris sending heavies in hot pursuit and Roman remaining tantalizingly elusive. Until, that is, Boris was shopping at Dolce & Gabbana (don’t worry, that’s fully the most vulgar detail of the drama) and on leaving, noticed his long-sought target two doors away in Hermès. With not a second to spare, he ordered a bodyguard to grab the writ from his car’s glove compartment — naturally, he never left home without it — and barged into the store. Amidst the intermingling odors of overpriced leather and excited bodyguards, he thrust the writ at Roman with the immortal words: “It’s a present. From me to you.” The envelope fell to the floor as the younger man recoiled, seemingly under the impression, said an onlooker, that “if he didn’t have physical contact with it, then the writ wouldn’t be served.”

Though not particularly well-known in the United States, Roman Abramovich, a twice-divorced father of six, is the most famous non-public figure in Britain thanks to his ownership of Chelsea Football Club, his relationship with beautiful socialite Dasha Zhukova and of course his lifestyle of flitting between English mansions, French châteaux and various super-yachts on his lavishly appointed Boeing 767. Notoriously cagey, he had never spoken in public and certainly hadn’t volunteered any specifics on how a penniless Jewish orphan, raised in the bleak and anti-Semitic environment of 70s Communist Russia, became one of the richest men on the planet. But not only was his erstwhile mentor’s legal action a threat to Roman’s vast wealth, it also meant that he’d eventually be compelled to answer questions, under oath, about the shadowy “Wild East” days of post-Perestroika Russia, when a small group of men profited from the country’s de-nationalized industries to a staggering degree.

A less auspicious beginning to a spectacular life is hard to imagine: before Roman’s first birthday, his 28-year-old mother Irina died from blood poisoning caused by a back-street abortion. Just 18 months later, his father Arkady was at work, supervising some construction, when the arm of a crane broke off and crushed his legs. A few days later, he died in hospital. Roman spent his childhood living with relatives, and after an undistinguished school career and a grueling stint in the army, the Russia he knew — constant shortages of basic necessities, a complete dearth of luxury, capitalism of any kind outlawed — was finally starting to change with the new Gorbachev government.

In his early 20s, Roman was an engineering student who also dabbled in black-market trading, and once commercial activity was legalized, in 1987, he launched a successful business selling plastic toys. Various other profitable enterprises followed, and by the time President Yeltsin’s economic reforms were underway in the early 90s, the ambitious young entrepreneur was making huge sums in oil trading, buying domestic crude oil at cut-price rates and selling it on the international market.

Then came the chance encounter on which his grand destiny would pivot: on a yacht in the Caribbean, Roman was introduced to Boris Berezovsky, a car dealer, media mogul and confidante of Yeltsin. The two men struck up a partnership and by 1997 had taken control of a previously state-owned oil giant, Sibneft, via complex shenanigans that involved loaning $100 million to the desperately cash-strapped government, promising Yeltsin positive TV coverage in the run-up to the election, bidding at rigged auctions of company stock and, allegedly, buying up share vouchers from oil workers unaware of their value. (“We didn’t understand the concept of owning shares,” explained Vladimir Ramazanov, “and there wasn’t even a Russian word for ‘privatisation.’”)

By 2003 Sibneft, which had been acquired for under $200 million, was worth $15 billion. Today, 45-year-old Abramovich has parlayed his share of that magical jackpot into a personal fortune estimated at $13.4 billion, putting him neck and neck riches-wise with Mark Zuckerberg. (Sorkin, if you’re reading, I see Jake Hoffman as Abramovich, James Gandolfini as Berezovsky and Natalie Portman as Zhukova. You’re welcome.)

Of course, the scariest thing that’s ever happened to Zuckerberg is probably meeting Snoop Dogg, whereas you don’t arise victorious from the stratospherically high-stakes free-for-all of post-Iron Curtain Russia — an environment described by Abramovich’s barrister as “medieval” — without enduring more than a few sleepless nights. Underworld extortion, rampant political bribery and an omnipresent threat of violence were the norm, and supposedly, someone was murdered every three days during the so-called “aluminum wars,” when the battle for privatized stock became so intense that ordinary Russians who worked in the industry — smelt managers, company executives — were in constant fear for their lives.

It was against this Ballardian backdrop that, with the help of paid protection from gangsters and his all-important political connections, Abramovich bought the Krasnoyarsk aluminum smelter in Siberia, which he merged with the aluminum assets of fellow fledgling oligarch Oleg Deripaska to create one of the largest aluminum companies in the world. (Deripaska is currently embroiled in a very similar lawsuit to Abramovich, having been sued by Uzbekistani-Israeli entrepreneur/Interpol fugitive Michael Cherney for $3 billion. On the plus side, a group of models once named Deripaska as the oligarch they’d most like to meet, which rather begs the question why no magazine publisher has launched a glossy tabloid — Oligarch Weekly? — dedicated to investigations like Which Super-Yachts Have Seen the Hottest Action? and paparazzi shots of Russian billionaires whose gray roots and man-boobs prove they’re Just Like Us.)

While he emerged unscathed from that murky chapter of history, Abramovich must view the tribulations of his fellow oligarchs as chilling evidence that he can never stop looking over his shoulder. Berezovsky fled his homeland after being accused of fraud and embezzlement of funds from Aeroflot, the Soviet national airline he helped corporatize and in which Abramovich owned a 26% share. Britain declined to extradite Berezovsky, who was convicted of financial crimes in absentia and sentenced to six years; meanwhile, British authorities arrested and deported a Russian hitman who was sent to bump him off. Media tycoon Vladimir Gusinsky, who created a bank before launching Russia’s first independent TV channel and newspaper, has repeatedly been pursued by the Kremlin for allegations of fraud and embezzlement and now lives in Spain and Israel. And the most startling fall from grace is that of Mikhail Khodorkovsky, once the richest man in Russia and the owner of oil company Yukos, which in 2003 was set to merge with Abramovich’s Sibneft. Now Khodorkovsky sews police uniforms for pennies a day in a Siberian prison camp, where he’s serving sentences for fraud, tax evasion, embezzlement and money laundering, and is deemed a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.

A crucial difference separates Abramovich from his beleaguered countrymen: one way or another they all made the fatal error of antagonizing Putin, whereas Roman and Vladimir have stayed total besties, a state of affairs partly attributable to the former’s widely acknowledged low-key charm and gift for diplomacy, or what Berezovsky refers to as his “genius for persuading people to trust him.” Cannily, he has also maintained financial and political ties with Russia: he still claims residency there, is chair of the legislative assembly in Chukotka, the remote Siberian province where he served two terms as governor and has gold mining interests, and is expected to heavily fund Russia’s hosting of the 2018 Soccer World Cup, as Putin has made plain: “It’s no big deal,” he said on TV, “he won’t feel the pinch.”

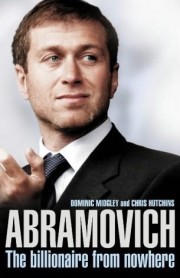

Nevertheless, the authors of Abramovich biography Billionaire From Nowhere, Dominic Midgley and Chris Hutchins, speculate that his 2003 decision to pay £140 million for Chelsea Football Club — or “Chelski” as it’s now known — may have been an “insurance policy,” in case the love fest ever hits the rocks and Putin turns against him: “By buying Chelsea, the man who was the world’s most obscure billionaire became a household name in his adopted country at a stroke. In the event of an attack by Putin, which British Prime Minister would be brave enough to deny him asylum?” Be that as it may, Roman could hardly have held his head up among all the other filthy rich plutocrats without his very own football team to play with; after all, to give just a few examples, Silvio Berlusconi owns A.C. Milan, Paul Allen owns the Seattle Sounders, and François Pinault owns Stade Rennais (no, me neither). Reputedly eager to turn his team into a world-class club, Comrade Chelski recently broke the British transfer fee record by buying Liverpool player Fernando Torres for £50 million. (Also, it was my pleasure to read that Roman is set to banish scourge of this column Ashley Cole.)

Setting new spending records must, one imagines, be about the only activity that gets a jaded multi-billionaire’s endorphins flowing. Hence Roman buys — on an almost daily basis, it feels like — the most expensive houses, he owns the world’s most expensive yacht and this past January 31st, he threw a party on St Barts that was widely and obligingly reported as “the most expensive 2012 new year’s eve bash.” It was thus a matter of crushing disappointment to the nation’s tireless documentarians of extravagance when the divorce settlement paid to his second wife Irina, the mother of five of his children, which had promised to be the biggest in history, only just squeaked into the top five. Irina accepted $300 million, which Roman had completely forgotten was in the pocket of those jeans anyway.

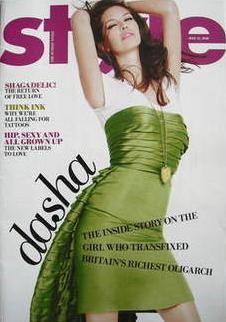

As a free man, Roman could openly romance his erstwhile mistress, Dasha Zhukova. Lissome fashionista Dasha, a billionaire’s daughter 15 years her boyfriend’s junior, was born in Russia, but grew up in L.A. and then moved to London. Although neither of them is British, they won honorary status as Her Majesty’s true subjects via the country’s most hallowed tradition: a lurid front page tabloid exposé! The October 8, 2006 edition of the News of the World was headlined RED ROM AND THE BRUNETTE, and breathlessly revealed how the lovebirds were illicitly rendezvousing on several continents, prompting Roman to issue a publicist’s denial and Irina to summon London’s priciest divorce lawyers.

Dasha and Roman have been together ever since and have a two-year-old son, Aaron Arkady. Inspiringly, motherhood has scarcely put a crimp in Dasha’s busy schedule of attending fashion shows with her gilded clique of girlfriends (who include, as Eurotrash-watchers will know, Olympia Scarry, Charlotte Casiraghi, Eugenie Niarchos, Tatiana Santo Domingo and Margherita Missoni) and editing Garage, the magazine she launched as an offshoot of her Moscow art gallery of the same name. Soon after the gallery’s 2008 launch, when a journalist asked about her favorite artists, Dasha notoriously responded “I’m, like, really bad at remembering names.” You’ll be shocked to hear that this caused much sniping from jealous cynics, who seemed to be laboring under the sad delusion that one’s status in the art world should be related to something other than access to a bottomless pit of cash.

I mean really, why bother remembering names when all you have to do is point at the page in Sotheby’s catalogue with the most eye-watering pre-sale estimate? With such able assistance from Dasha, Roman has spent the GDP of several small nations on paintings like Lucien Freud’s “Benefits Supervisor Sleeping,” Francis Bacon’s “Triptych,” and Picasso’s “Nude, Green Leaves and Bust.” He’s also been named as an interested buyer of Munch’s “The Scream,” along with the Sheik of Qatar, Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani. That’s a cat fight waiting to happen if ever there was one, especially since poor old Hamad is one of the megayacht owners who’ve been utterly humiliated by Roman’s purchase of what is not so much a boat, more an ostentation broadcasting system that floats. The biggest private yacht in the world, The Eclipse is 557 feet long, has twin helipads, bullet-proof glass, armored plating, two swimming pools, a disco, missile detectors and an anti-paparazzi shield that sweeps infra-red lasers around, detecting cameras and shining lights to prevent photographs being taken. Sounds potentially hazardous to human retinas, so fingers crossed that any blindings occur in litigation-exempt international waters.

That said, it’s probably only a matter of time before similarly state-of-the-art technology graces all of Roman’s residences, so as to avoid any awkward repetitions of last month’s gleefully reported story: residents of a building opposite Roman and Dasha’s house on Cheyne Walk, in Chelsea, were outraged to receive letters from the Russians’ estate agent requesting access in order to “understand the vista” from their windows. Seethed one posh neighbor: “I resent the idea that we are being perceived as potential peeping Toms. It certainly wouldn’t cross our minds in a million years to do so.”

Such indignant reassurances are unlikely to sooth privacy-obsessed Roman, who’ll still be reeling from the most stressful intrusion into his life he’s ever had to endure: the sensational trial of Berezovsky v. Abramovich, which finally kicked off at London’s High Court last October, lasted four months and is, needless to say, the most expensive private litigation in history. The crux of the case is Berezovsky’s claim that in 2001, Abramovich blackmailed and bullied him into selling his portion of Sibneft for a mere $1.3 billion, a fraction of its worth, warning that if he didn’t, the state would confiscate his assets anyway and he’d be left with nothing. Abramovich strenuously denies this, insisting that Berezovsky — described in court as a man with “truly prodigious powers of self-deception” — never owned any part of Sibneft, that they were never business partners, and that he had paid him billions for protection and political favors at a time when corruption was the only game in town.

“There was no rule of law,” explained Abramovich’s barrister, Jonathan Sumption QC. “Police were corrupt. The courts were unpredictable at best … Nobody could go into business without access to political power. If you didn’t have political power yourself, you needed access to a godfather who did.” Muddying the waters still further is the absence of any physical evidence. “Russians have a mistrust of committing anything to paper or working with formal documents,” lawyer Ekaterina Sjöstrand told Tatler. “This is for historical reasons and goes back to the Cold War and Soviet times, when documents were used against Russians by the intelligence agencies and authorities.” So the court heard how deals were done with a handshake over meetings in gentleman’s clubs or airport lounges and instead of bank transactions, suitcases stuffed with cash were covertly exchanged, heist movie-style.

That it all ultimately boils down to he said/he said scarcely detracted from the schoolgirlish thrill that swept through the nation at the mere idea of Abramovich discussing the enigma-shrouded origins of his wealth. The Daily Mail’s Neil Ashton spoke for many when he opined that “the most fascinating aspect of this case is hearing from Chelsea’s silent and mysterious owner.” And when he was questioned about the channels by which he took control of Sibneft, we even got a sense of how he views the criticism so often leveled at him: that by plundering Russia’s natural resources for huge profit, he has contributed to the continuing poverty of its people. “If we didn’t do so,” he pointed out, “someone else would have done so.” Such sangfroid notwithstanding, on the stand he was apparently palpably shy and nervous, even shaking at times, an image that may help to humanize this hitherto remote and borderline-mythical figure. What would humanize him even more, of course, is being divested of $5.8 billion.

That decision now lies in the hands of the presiding judge, Justice Dame Elizabeth Gloster, who’ll deliver her verdict in the next month or so. Whichever way the wind blows, we can be sure that Roman Arkadyevich Abramovich is now ever more convinced of his favorite maxim: “Money loves quiet.”

Previously: Kate Middleton, Amy Childs, Jordan and Boris Johnson

Emma Garman no longer lives in her native UK, but she still watches lots of its TV. She’s also on Twitter.