Miss Simone's Ninth-Grade Hip Hop Appreciation Class in Brooklyn

Earlier this month, Becca Simone’s music appreciation class at Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School in Brooklyn, NY, sat down to a test. It was four pages long. The test started with:

1. List three characteristics about the Bronx in the 1970s:

2. What type of music was popular during the 1970’s when the hip hop movement was beginning?

And once the students got through those (and the 28 questions following) they were met with the essay question:

Part 2. Write a brief (about 5–8 sentences) response about the hip hop movement. What about it do you find interesting? How has the music changed over the years (i.e., in terms of today)? If you were alive during that time, do you think you would have liked the music and been a part of the movement?

Five to eight sentences may not seem like a lot, certainly not quite a long-form culturally biased SAT essay, but it’s certainly getting kids to organize their thoughts and put pen to paper.

FDR High School is not situated in hipster Brooklyn; there are no locavore banh mi food trucks and the facial hair is absolutely sincere. Some say the neighborhood is called Mapleton, which is about as un-Brooklyn as you can get. Whatever you call it, it’s on the northern edge of Bensonhurst and the southern edge of Borough Park — an area of bustling diversity, with enclaves of the recent and not-so-recent immigrants from all corners.

And so FDR High is one of the more diverse high schools in the NYC school system; 42% of the student body learned English as a second language, and there are 37 different first languages spoken by the students. It’s a public school, which inevitably conjures the word failing. But it’s also the day-time home of 3038 kids, grades nine through twelve.

Miss Simone — which is what she is called in class, and who is an acquaintance of mine — is in the middle of her seventh year as a public school teacher, which she has largely spent teaching Spanish. Over the winter break, a pregnancy leave left a vacancy for a teacher in the music appreciation course, and Miss Simone ended up with it. She was given a loose curriculum, but told that it was “open-ended.” Miss Simone, a fan of hip hop since growing up in New Jersey, saw daylight and made a break for it. And so this is the school’s first semester-long course devoted in its entirety to the history of hip hop. The students are freshmen in their first year at FDR, with a few juniors that took the course at the behest of Miss Simone.

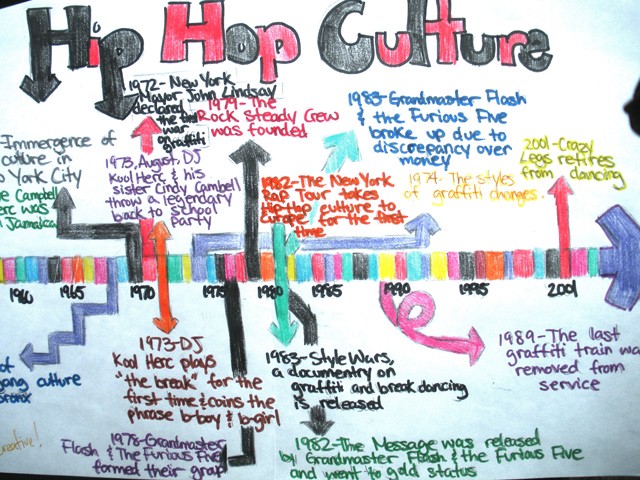

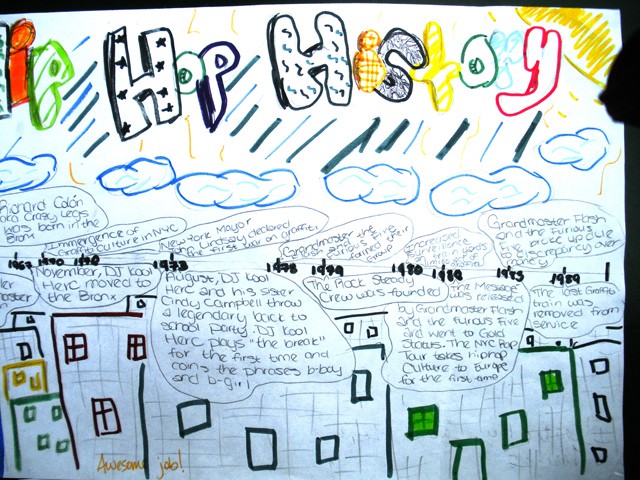

I asked Miss Simone if her students were showing any particular response that was different from the other classes she’s taught. Not really, she said — maybe a raised-eyebrow or two on the first day of class. But she did start to notice a difference: “They really started to get into it when I started to talk about the first hip hop party DJ Kool Herc and his sister threw in the rec room of 1520 Sedgwick Avenue in 1973. His sister wanted some clothes, and they wanted to make some money. They charged girls a quarter, and boys fifty cents, and they paid a guy to switch the lights on and off like a strobe light. These funny little details, that was really exciting to them.” Miss Simone did try to talk a friend to come in for a break-dancing demonstration, but the friend balked. But she did get permission to take them on a field trip to Five Pointz, a graffiti museum in Queens.

Teaching the history of hip hop is not a novel thing. Such a course is available at colleges, private and public, all over the country. It’s a music form that’s nearly forty years old — it’s older now than rock and roll was when hip hop started. The topics Miss Simone covers, like the birth of scratching and pop-and-locking, may sound jejune, but these students were born in 1996 and 1997. These are now cultural artifacts that were created a full generation before they were born.

Playing devil’s advocate, I played the upset parent and asked Miss Simone how she would respond to accusations that teaching public school kids about hip hop is a waste of time and taxpayer money. She said that while the class may be about a musical style, at the same time the students are reading and writing and learning. Hip hop is the carrot to engage them. And: “I’m not only teaching them about the history of hip hop, but also the history of the city they live in,” she said.

Miss Simone is naturally cautious about the course; it’s not exactly the best time to be a public school teacher in America, let alone in New York. In the past few years, public sentiment turned on public school teachers, even as the Great Recession squeezed school budgets nation-wide. The morale of public teachers in the United States is at the lowest it’s been in twenty years, with a significant drop-off in the past two years, which is perhaps not coincidentally how long ago the documentary Waiting For Superman was released. Closer to home, in NYC, the school board has begun to grade the performance of public school teachers and post them online.

In 2010, FDR High was designated a “transformation” school by the NYC Department of Education, which enlisted it in a program to give a leg up to underperforming schools, with grant money and a reevaluation in three years. Even with a “B” progress report grade (PDF) from the DoE for the year 2010–2011, the Mayor announced in January that FDR would be one of 33 schools to be yanked off the “transformation” list and put into “turnaround.” Those schools will undergo a “soft closing” at the end of this scholastic year. What this categorization means in practice is that FDR will be closed and then immediately reopened and renamed — retaining only half of the teaching staff, with new teachers replace the departing teachers. Miss Simone’s job in the New York City school system is safe, as she is tenured, but it’s not written in stone that she will be returning, and if she does, her school will no longer be named after our thirty-second president.

In NYC, there are 75,000 active public school teachers. For a point of reference, there are currently about 34,500 police officers in NYC, so there are almost twice as many teachers. As marginalized as some would have our public school teachers, there are certainly a lot of them in the five boroughs.

Miss Simone’s music appreciation class is not going to change the world, nor is it meant to. In fact, it’s almost unfair to single out this one teacher’s efforts, as I’m sure that there are stories like this all over the city, all over the country, no matter the No Child Left Behind hoops that have to be jumped through, no matter the efforts to paint public school teachers as villains interested only in cushy pensions and seasonal employment. Miss Simone did not intend this to be the beginning of a movement, or a flag planted, or a statement in any other flavor. She’s doing her best in what can prove to be a thankless environment.

I asked how the kids did on the test (and you can take it here yourself, if you like). Miss Simone said the average score was in the 80s. “Only one student failed and he entered the class late,” she said. Not too bad.