I Sold My Soul to the Department of Homeland Security

Not long ago, I got a letter from my airline of choice, explaining that they’d partnered with the fine people in the U.S. government to help prevent terrorism faster. If you’ve spotted people at airports being whisked into a special line, where they don’t have to take off their shoes, don’t have to take out their laptops or even remove their belts, you’ve already spotted this program in action. The rollout of TSA PreCheck — branded as TSA Pre✓™ — started just back in October, with seven airports, including Los Angeles and Miami, and just for American and Delta passengers. Then the TSA announced they’d be including JFK airport — which just happened last week — and then O’Hare and Washington National this month. Throughout the year, airports from Honolulu to Tampa will be added.

Now, the airlines were providing test subjects to the feds by including their frequent fliers — but only some of them, chosen by who-knows-what criteria. The invitation process was opaque: you’d get an invitation or you wouldn’t. I checked my American Airlines account, and I wasn’t one of the special elect who’d been “opted in.” But you could also force your way into the program, by having a frequent flier number and registering with one of the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Trusted Traveler programs. In a strange fit of annoyance — who likes to be excluded? — I suddenly found myself filling out a lengthy application with the U.S. government. Also, sending them $100 for the privilege.

The Global Entry program just officially became a permanent U.S. government program. It has about 260,000 members. Global Entry is intended for frequent international travelers; it “pre-certifies” people for customs. They get to go to a kiosk and scan their fingerprints in and make their immigration declarations and get ushered through. So far it’s just available at 20 international airports.

Their application wasn’t too invasive: the address of everywhere you’ve worked and lived for the last seven years, some declarations about your lack of criminality, that kind of thing. I’ve never been charged with a crime, so I apparently sailed through and got a letter through the GLOBAL ONLINE ENROLLMENT SYSTEM website: “We are pleased to inform you that your U. S. Customs and Border Protection, Global Entry membership application has been processed and you are now invited to visit an enrollment center to complete the enrollment process.”

Invited! This meant two things, I think. One is that they don’t check, or at least count, your credit score. (I don’t have one.) I am also assuming, perhaps incorrectly, that this means that I am not on the list of reporters that Homeland Security tracks on Facebook and Twitter. Or perhaps I am, and I passed the test.

I made an appointment, and then, when the day came, I got nervous. I put on an adult shirt, with buttons! They referred to this as an “interview,” but I had no idea what they might possibly ask me. I figured it was going to be like the DMV, but as if the DMV was run by the CIA.

The Global Entry office, which is located opposite the “Avianca Airlines” check-in counter in the Miami airport’s international terminal, was a small dark waiting room with a bright room inside it. There was no one in the waiting room. A lone guy waved me into the inner office. I gave him my passport and driver’s license and then started telling him about how I had all this proof of address information (my license has an old address). He did not really care at all about that.

He took my fingerprints with their groovy and frightening scanners, and also took my picture with his little webcam. We talked a little. He asked me when was the last time I’d left the country. I couldn’t remember. I think I went to Canada like 15 years ago? He looked a little surprised — most applicants of course do this so as to blow by customs. I told him I was just doing this for the expedited domestic screenings. We talked about America for a while, and we agreed that you could pretty much get it all right here in the U.S. of A. Why leave? Mountains with snow! Tropical beaches! Big cities! The U.S. has it all! We totally agreed that America was great.

Then he slapped a little white sticker with some initials on the outside back cover of my passport, and then I was suddenly done. (The sticker reads “CBP,” which I assume stands for Customs and Border Protection, and according to the FAQ, “The Global Entry passport sticker identifies you as a Global Entry member to CBP personnel.”) There were no trick questions about whether I’d been a drug mule or anything. After I got home, I got another electronic notice.

We are pleased to inform you that your U. S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), Global Entry program membership has been approved. You may use the program as soon as you receive and activate your new Global Entry card.

If you enrolled in Global Entry, you may begin using the kiosk immediately. Global Entry cards are only issued to Global Entry members who are U.S. citizens, Lawful Permanent Residents or Mexican Nationals (who are not current SENTRI members). Global Entry cards are not valid at the Global Entry kiosks.

Global Entry cards… are not valid… at the… Global Entry kiosks.

I spent some time trying to parse that and then decided not to worry about it. I immediately went to the American Airlines site and put my new ID number in the “Customs and Border Protection ID” of my frequent flier profile page. There’s a slot for that — right by the slot for “Redress Number.” A “Redress Number” is a TSA-assigned number for “customers who believe they have been mistakenly matched to a name on the watch list.” There was something so telling about how the airline didn’t even feel a need to explain, or capitalize, “watch list.”

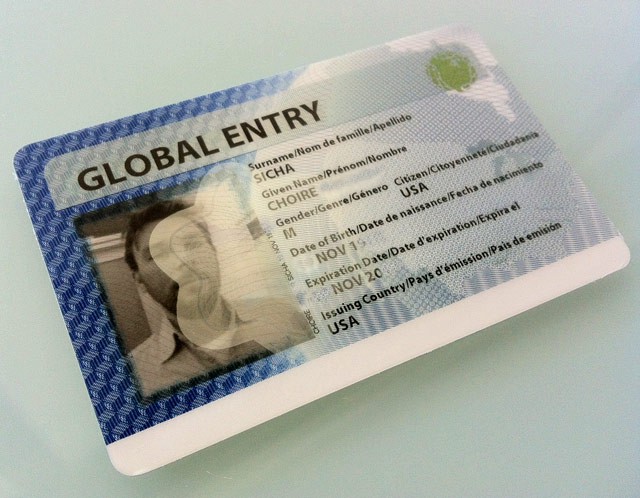

Eventually my card came, and I activated it within 30 days, as per their instructions.

I suppose I had, without even phrasing it aloud, asked and answered a question. Which do I hate more: minor inconvenience? Or an overreaching and intrusive state that divides people into classes based, at best, on one’s ability to pay for entry into the superior class, and, at worst, on one’s ability to pass a government test with no explanation of the criteria?

To be fair, there are criteria, five in all. The first four include that you can be denied if you lie on the application, if you are subject to a pending investigation, and, troublingly, if you “have been convicted of any criminal offense.” (That makes it clear how we’re certifying a “non-criminal class.”) But the fifth is quite broad: applicants may be denied if “they cannot satisfy CBP of their low-risk status or meet other program requirements.” The old catch-all.

Here’s an interesting data point: American Express reimburses their Platinum and Centurion cardholders for the $100 fee.

* * *

“Our security officers here behind us can focus more time on those we know the least about,” is how John Pistole, the chief TSA honcho, explained the program at a press conference at JFK.

“Expanding TSA Pre-Check is about more than just speeding up travel. It’s part of a fundamental shift in how we approach aviation security,” is how his boss, Homeland Security honcho Janet Napolitano, recently put it.

And what a trade-off: the convenience of TSA Pre✓™ isn’t even guaranteed to enrollees. They can still give you the full pat-down at any time, or the special pre-approved screening line can be shut down due to staffing issues. As well, as the TSA put it, “no individual will be guaranteed expedited screening in order to retain a certain element of randomness to prevent terrorists from gaming the system.” So we government-approved fliers can’t even rock it to the airport at the last minute, else they might get hosed, so as to prevent terrorist from gaming the system.

Also, I am pretty sure that if I could go back in time to tell teen-aged me that I was going to willingly sign up for a Homeland Security investigation and stamp of approval, I’d spit in my own face.

The Global Entry card, which is not valid at the Global Entry kiosks (this means, it turns out, just that you must use your passport at the kiosks), came in a thick little paper pouch, white and blue, with a blurry globe with a blurry North America in view. It also had a warning: “Protect your card’s sensitive electronics — and your privacy. Keep the card in this sleeve when not in use.” I wonder if the RFID chip in my new passport will fight with the RFID chip in my Global Entry card. Presumably they’ll conspire to make it extra-easy for any government agency to find me wherever I go. Right now the card and the passport are about 12 feet apart from each other, and I’m right in the middle of them.